There will be blood

By Jane Bryce

La Soga (The Butcher’s Son), directed by Josh Crook (100 minutes)

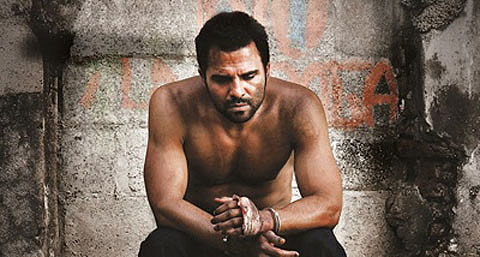

Manny Perez in La Soga. Image courtesy the trinidad+tobago film festival

The fact that it took me a while to figure out where this film was set (until I checked the website, I thought it was Mexico) shows how unaccustomed we are to seeing films from the Dominican Republic. La Soga is said to be the first that has broken through into the cinema mainstream; in spite of the fact that the director is American, it is a fully Dominican production, written by the Dominican-American immigrant actor Manny Perez, who also stars as Luisito. When La Soga premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival it was, incredibly, the first time a Dominican film had ever been screened there.

Director Josh Crook has said in an interview with the Huffington Post that he was “sick of shooting in New York and pretending it was an interesting place.” Artists, he claimed, had been driven out of New York by property prices and commercialism. He wanted to “be part of something that means something to somebody,” and it was reading Manny Perez’s script that took him there. In the DR, he found a place where “they don’t depend on corporations to define who they are . . . for an aspiring artist, [it] was not a film production, it was a state of ecstasy.”

In spite of the bleakness of its subject and the hard-eyed realism of its perspective on poverty and violence, something of this “state of ecstasy” manages to pervade La Soga, making it a crime thriller with a human face. From the opening sequence, the joyful bachata, Latin dance rhythms, and popular songs of the sountrack are an upbeat counterpoise to the often distressing events we and the characters are forced to witness. The film was shot on location in “real” places; one assumes many of the people standing around, living their lives, are “real” too. Violence is treated almost casually, as a fact of life, real-time entertainment for kids with nowhere else to play. But alongside the violence are scenes of astonishing tenderness that almost seem to belong in another film altogether. This quality is largely the accomplishment of the director of photography, Zeus Morand, whose eye lingers on details in the environment — the texture of a wall, a child’s shadow, domestic animals, the slo-mo arc of a swing — that emphasise the neighbourhood’s vitality and the complexity of its relationships, as well as its brutality and casual cruelty.

This brutality is encapsulated in the sobriquet “La Soga” given to Luisito, who becomes a murderer aged around eleven to avenge his father’s death, and spends the next twenty years hunting for the killer who got away. Literally “rope” or “hangman’s noose,” the nickname denotes a hitman from whom there is no escape. The macho cliché is complicated, however, by Luisito’s backstory, shown in sepia-tinted flashbacks, especially his childhood friendship with a young girl, Jenny, and the empathy it inevitably elicits for Luisito as victim of a system shown to be irredeemably corrupt. At the level of iconography, the motif of animal butchery (the film’s alternative title is The Butcher’s Son) drives home the cynicism with which the powerful treat the rest of society. The young Luisito, after playing at adopting a pig with Jenny, is initiated into manhood by his father’s lesson in how to kill the same pig, a scene which lasts a full minute on screen and feels like ten. Cockfighting, a routine pastime, visually embodies the philosophy of survival which drives the inhabitants. Forget disclaimers about animals being hurt: in the face of so much human suffering, such niceties are risible.

La Soga not an easy film to watch; at times, indeed, it’s unbearable. But the fact that the violence is not mediated, romanticised, or stylised gives the film a strong moral edge. You feel it’s got something to tell you, an urgent message that keeps you watching. Meanwhile, the love affair with a now grown-up Jenny (played by Denise Quiñones) that allows Luisito’s buried humanity to reemerge is utterly affecting, a chance at redemption that evades romantic cliché. This film does more than put the DR on the cinematic map — it confronts the audience with moral questions that linger far beyond the action.

•••

This review is part of a special section on recent Caribbean film, supported by the trinidad+tobago film festival 2010

•

The Caribbean Review of Books, September 2010

Jane Bryce is professor of African literature and cinema at the University of the West Indies, Cave Hill. Born and brought up in Tanzania, she was educated there, in Britain, and in Nigeria. She founded the Barbados Festival of African and Caribbean Film, which ran for five years, and now co-curates the Africa World Documentary Film Festival at Cave Hill.