What’s in a name

By Bridget Brereton

Archibald Monteath: Igbo, Jamaican, Moravian,

by Maureen Warner-Lewis

University of the West Indies Press, ISBN 978-976-640-197-9, 367 pp

Maureen Warner-Lewis is a Trinidadian linguist and social historian, based at the Mona campus of the University of the West Indies, whose brilliant studies of African language and culture in the Caribbean have enriched our understanding of the region’s painful and tragic, yet resilient and creative, historical experience. Her previous works examined Yoruba language and cultural influence on Trinidad, and, more recently, Central Africa’s enormous contribution to the shaping of the whole region. Now she narrows her focus to Jamaica, and to one man’s life story and spiritual odyssey; but in doing so, she succeeds in illuminating the social and cultural history of a people at the time when slavery was dying and a new society was slouching towards Bethlehem to be born.

Archibald Monteath is a brilliantly reconstructed biography of a man who was born in “Igboland” (modern south-eastern Nigeria) around 1792, kidnapped and enslaved as a child around 1802, taken to Jamaica and bought by the Monteath family, worked as a human chattel, “promoted” to headman on a livestock farm, and finally self-liberated by purchase in 1837, one year before the final end of slavery. It is the story of a man who was called Aniaso at birth, had the “slave name” Toby imposed on him as a child in Jamaica, and proudly took the names Archibald John Monteath on his baptism in 1821, when he was still human property. And it traces his spiritual journey from a deeply religious Igbo community to his conversion to the Moravian faith and his emergence after 1837 as a full-time church worker much respected by his European colleagues in the close-knit Moravian Jamaican mission.

As Warner-Lewis says, this book is a “microstudy of the life and times of a significant individual” which, when painstakingly contextualised by wide-ranging archival research, allows us to deepen and sharpen our understanding of human and social relations at a seminal period of Jamaican and Caribbean history. In this respect, it is part of the newer kind of social and cultural history, which is moving away from the “social scientific” type, which was highly “structural” in approach and tended to downplay human agency and individual lives. Instead, a single life-story — or many of them — are used as windows through which to examine whole social formations and historical developments. (Simon Schama’s Citizens, on the French Revolution, or his more recent Rough Crossings, on the tragic story of the enslaved African-Americans who fought on the British side during the American War for Independence, are well-known examples of this genre of historical writing.) Warner-Lewis’s work also exemplifies the trend towards cultural history and cultural studies, with a strongly cross-disciplinary approach; as a linguist who writes brilliant social and cultural history, her own hard-to-label academic location makes the point, though in the book now being reviewed, she shows her mastery of the historian’s more conventional kinds of archival and textual research.

If Warner-Lewis’s approach to social history through a single life-story reflects these recent trends in the academy, her chosen hero is not altogether politically correct. And she shrewdly speculates that this might explain why his autobiographical texts have been more or less ignored by scholars searching for sources on slavery and emancipation. The deep Christian (Moravian) conviction, the fervent piety, which pervade his writings may be distasteful or even contemptible to some. As it happened, I read this book at about the same time as a work by D.M. Stewart, Three Eyes for the Journey: African Dimensions of the Jamaican Religious Experience (2005). While in many ways an interesting study, it seems to insist — on ideological or theological grounds — that a Jamaican conscious of his or her African heritage cannot be a Christian, that African-Jamaican Christians (at least, of the orthodox kind) are, at a profound level, inauthentic beings. Such a mindset is unlikely to appreciate African-born Monteath, who dedicated the second half of his long life to the service of a Christian mission and its European ministers.

Even more politically incorrect, Monteath’s autobiographical writings were not produced for the antislavery agenda, as the far better known History of Mary Prince and several other similar ex-slave narratives were, and do not fit the conventions of the antislavery discourse. His story “does not satisfy the post-1970s unidimensional lionisation of the slave as resister, runaway, or rebel,” Warner-Lewis notes; no “horrors of slavery” vividly described, no frontal attack on the enslavers, can be found here. Worse, he portrays himself as wholly loyal to his owner’s family during the great rising of the Jamaican enslaved in 1831–32, which took place in the very region where he lived. Not a conventional slave hero, then; but, as Warner-Lewis so successfully demonstrates in this book, his life story, “painstakingly mined, reveals useful nuances about the varied experiences of Caribbean slavery and the subsequent evolution of a peasant society.”

The life story would have remained unknowable, of course, if Monteath had not collaborated with Moravian missionaries in the production of autobiographical texts in the 1850s, when he was already in his sixties and had been a full-time Moravian “helper” since 1837. In her first chapter, Warner-Lewis discusses the complicated history of these texts, and what happened to them. Monteath was a highly respected African-Jamaican church elder, and the mission wanted to publicise and commemorate his life and Christian journey in a sort of expanded “conversion narrative.” More than one text resulted, in German (the Moravians were originally a German church) and in English; a German “sister” and an American “brother” worked to transcribe Monteath’s spoken reminiscences in Jamaican English Creole. (Monteath was literate but not a fluent writer, so the texts, Warner-Lewis carefully explains, were both autobiography and biography, with three “authors” collaborating.) These different texts have had a complicated publishing history, but — thankfully — their publication, in two languages and several periodicals from 1864, the year of Monteath’s death, up to the appendices in the present book, has ensured that his story can be retrieved from the great silence of the unknowable past.

•

Aniaso was born, Warner-Lewis deduces, around 1792 in the large region now known as Igboland, one of the West African “stateless societies” without a centralised government but forming a distinctive linguistic/cultural area; this is the culture so brilliantly evoked in Chinua Achebe’s novels, especially Things Fall Apart and Arrow of God. His lineage on both sides was distinguished, and as the son of a noble family, he told his Moravian colleagues, he was looking forward to the ichi initiation rite, a painful process of facial scarification on teenage boys which was the necessary prelude to taking high titles as an adult. He must have known that he was born into a noble family and destined for an honoured place in his society, and Warner-Lewis suggests that this consciousness sustained him through the horrors which befell him and made him determined to recover personal honour in Jamaica as a free man and an admired Christian leader. At the age of about ten, Aniaso was kidnapped by someone well known to the family, taken to the coast (probably New Calabar, a major slaving port on the Niger Delta), and sold to the enslavers. It was an especially vile act to kidnap the only son of a noble family and a future lineage head.

Arriving in Jamaica about 1802, five years before the end of the British transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans, Aniaso was bought by the Scottish-born planter John Monteath and renamed Toby. He worked at Monteath’s Kep estate, a pen (cattle farm) in western Jamaica, first as a “house boy” in the great house, then, as he approached adulthood, as a field labourer. But he never worked on a sugar estate — as did the majority of the enslaved people — and so never experienced the regimented gang labour and murderous work shifts between field and mill so typical of the sugar regime. In fact, as Warner-Lewis notes, the autobiographical texts say very little about his work as an enslaved chattel — his life as Toby. He does say that he was “promoted” to headman, effectively overseer, on a small pen adjoining Kep that was owned by the family. So Toby/Monteath became a “confidential slave,” one of the “head people,” without whom plantation Jamaica would have collapsed. His loyalty to his owners was amply proved by his actions during the great rising of 1831–32, as we have already noted.

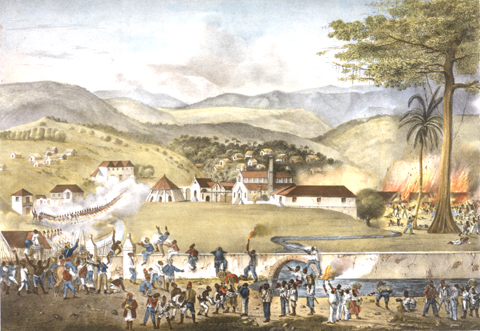

The Attack of the Rebels on Montpelier Old Works Estate (1833), by Adolphe Duperly. Image courtesy the Yale Centre for British Art

In case one is inclined to dismiss “Toby” as simply a Jamaican Uncle Tom, the texts make it very clear that Monteath always intended to become free; the secular, as opposed to spiritual, high-point of his narrative is his self-purchase in 1837. At the age of about forty-five, after over thirty-five years of unpaid labour for the Monteaths as chattel property and then (from 1834) as an apprentice, and in the teeth of opposition from his “young master,” James Monteath, he bought his release from apprenticeship for the very large sum of fifty pounds. For the rest of his long life, he was a full-time, salaried Moravian “helper,” preacher, and organiser, combining this with farming on his own land and marketing. He never worked for a planter again.

Toby threw away that imposed name forever in 1821, when he was baptised by an Anglican parson. In a fascinating discussion on naming among slaves and ex-slaves in chapter ten, Warner-Lewis points out that baptism implied a new name, a new persona, a move from the single imposed name — Toby — to a Christian name and a surname, as free people possessed. To bear two European names represented “an escape from the stigma of slavery,” it conferred visibility and respectability. Church membership became a key index of class status for free coloureds and blacks and for the enslaved, and baptism and new names symbolised all this: “Baptism birthed a new persona.” But what names to choose? Toby was erased, but Aniaso could not be revived in a society like Jamaica in the 1820s; the new names had to be European, the “borrowed tradition” was the only choice. Significantly, “Toby” didn’t take his names from his master James, with whom he had a rather volatile relationship, but from James’s brother, and significantly too, he took his two Christian names, Archibald John, reflecting his sense of status, even “grandeur,” as the son of a distinguished Igbo family.

A few years after his baptism, he came under Moravian influence, joining the church in 1827, almost immediately emerging as an activist and a leader, although he did not become a full-time mission worker until his self-liberation in 1837. From then on, he was a highly visible and successful preacher and leader in his church, an exemplar of whom the mission’s leaders were very proud; hence the effort taken to compile the autobiographical texts and to publish them.

This life-story is not a self-presentation of a brutalised victim, of a wounded individual, Warner-Lewis concludes. It is an account of a man’s “reclamation of a moral sense, of dignity, and of personal identity.” This was a person with agency and self-confidence, on a life-long “quest for honour lost in childhood, and honour regained” though faith, self-liberation, and religious commitment. Moravian Christianity, she suggests, provided a moral code as strong as that of Igbo religion and society, and his freely chosen work for his church was a substitute for the life of honour he would have enjoyed in Igboland as a man from a noble family. Aniaso, Toby, Archibald John Monteath; Igbo, Jamaican, Moravian: Warner-Lewis brilliantly demonstrates how one person could negotiate between these names and identities without — however terrible the circumstances which forced choices on him — ever giving up his authentic being(s).

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, May 2008

Bridget Brereton is professor of history at the University of the West Indies, St. Augustine. She is the author or editor of several books and many articles or chapters on the history of Trinidad and Tobago, and on the post-emancipation development of the Caribbean.