In pieces

By Anu Lakhan

Everything Is Now: New and Collected Stories, by Michelle Cliff

University of Minnesota Press, ISBN 978-0-8166-5593-9, 248 pp

If I Could Write This in Fire, by Michelle Cliff

University of Minnesota Press, ISBN 978-0-8166-5474-1, 104 pp

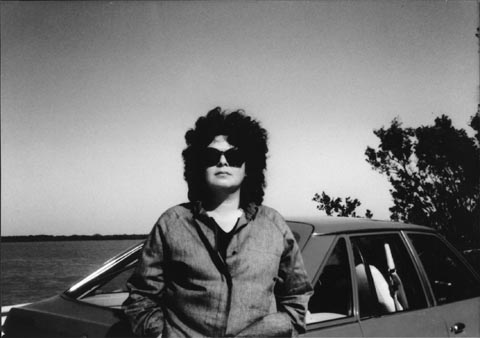

Michelle Cliff. Photo courtesy University of Minnesota Press

These are books that make you think of other books. They make you think of many things. They make you think.

Immediately, before a word from or about the author, the first example pushes its way to the fore. What I’d really like to say is: “They make you think. Period. End of sentence.” But I can’t do that — can’t even hear “Period. End of sentence” — without knowing myself beholden to Erna Brodber and her tight-lipped, stingy, honest summary of the transition from girl to woman in Jane and Louisa Will Soon Come Home.

This is a random start. I could have started anywhere.

Everything Is Now is Michelle Cliff’s third collection of short fiction (bringing together the contents of Bodies of Water (1990) and The Store of a Million Items (1998) with fourteen new stories). “Story” here is a strong word. Many of the pieces are nothing like stories. Some are essay-like, some memoir. The majority are fragments. What Cliff does with these shards of narrative is the beautiful, if befuddling, variable. A minor character in one piece becomes the focus of another. An aside early on finds substance in a later story.

For instance: three generations of women travel through time, geography, and theme. A green-eyed, scotch-drinking, sometime lesbian actress grandmother writes a letter to her granddaughter telling her (among other things one hardly expects to hear from one’s aged relatives) she hopes the “moment of [her] death will resemble a thrilling orgasm.” The letter is delivered after the grandmother’s demise. We meet her in a later piece as her younger self. This time, she is the no-good-will-come-of-her sister of a Boston doctor’s wife, who neglects to mention to them that she’s killed their adopted son. After a while, no matter the tale being told, this woman is easy to recognise. The focus shifts, but you know who’s there. At least — and this is no idle disclaimer — that’s what I think is happening. Most of the time, Cliff’s technique is heartily confusing.

In Shakespeare’s Kitchen (described by The New Yorker’s reviewer Sue Halpern as a “charming novel disguised as a book of short stories”), Lore Segal has her characters wandering freely through the stories and each other’s lives. Both main and lesser characters have appeared in her earlier books. Segal pulls off with subtlety what Cliff makes difficult through shredding. Still, as with Cliff, linearity does not seem to be an option Segal considers. Like Cliff, she deals with assimilation and outsiderliness, the past’s insistence on being present, the complexity of all actions and relationships. No great effort is required for their meeting in the same thought: Cliff, Jamaican- American (but it is Jamaica that has made her, Jamaica that shaped her, she says); and Segal, Viennese child-refugee, American via Britain and the Dominican Republic.

Though the concepts are similar, the hows and whys differ significantly. Segal’s prose is smooth, unruffled, gentle. In a way, assimilation has been achieved, “her accent has faded,” according to Halpern. Cliff does not — nor does she want to — lose her accent. The rhythm of writing is snap-and-sudden. An unpredictable object on the end of a string.

“Everything is now” apparently means just that. The segues, overlaps, relays, and replays do not inspire certainty. Where one story — or one person’s story — begins, and another ends, is seldom clear. In Beloved, Toni Morrison writes: “All of it is now, it is always now.” Cliff paraphrases, tightens the line to suit her title, but keeps the breadth of meaning. The bawdy grandmother at various stages of her life is just one example.

In the title story, a woman drives off a road into the past where she and her former self have iced tea and talk about the boyfriend she (they? is it “they” if it’s the past and present of the same person?) lost in the war. Too literal, perhaps. However, it is one of a very few pieces that can be read through without the sense that a page has been torn out of the book, and you’ll never know quite how you got to where you ended up.

There are thirty-five stories in the collection. That is, there are thirty-five separate entries, each with its own title. If each character has more than one story, if each episode is told from more than one perspective, if each telling is only a partial recollection, then, without the aid of mathematical formulae or inclination, I’ve no idea how many stories there really are. I’ll stick with the man with the wives and cats going to St Ives.

The success of this exercise in fragmentation varies from one piece to the next. It is far from perfect. At worst it is disorienting. At best — and there is a fair amount of “best,” and a fair range — the language is closer to poetry than prose:

A tabby moused in new mown grass.

(“Everything Is Now”)

The family had exited Eden more or less willingly.

(“Ashes, Ashes”)

Girlhood chums of my great-grandmother, they cluster together in my mind with all the other mad, crazy, eccentric, disappointed, demented, neurasthenic women of my childhood, where Bertha Mason grew on trees.

(“Contagious Melancholia”)

Outside this realm of judgement lies the thing that makes the work readable and, ultimately, forgives any shortcomings in style or structure: it is intentional. Cliff means for it to fall apart in your hands. Everything is in pieces.

Her own background — which is hers and Jamaica’s and the Caribbean’s, and that of all colonised people — is whole only inasmuch as it can be made to hold together. In the end, among the rifts, splits, and mixes of ethnicity, class and country, the individual — in order to be an individual — must be a bundle of all those parts. Brodber’s Jane and Louisa, mentioned earlier, is of similar lineage to Cliff’s current work. Both writers recognise that language — the Queen’s English and the English of Jamaica — can be as co-operative as it can be restraining. Both do a lot of dismantling of words and interpretations. Both work towards piecing together story, past, and understanding. They write heartily confusing narratives.

Everything Is Now is filled with allusions to old Hollywood films, classical music, historical references. These are the pins that fix the time of the story. Or the switch that calls up a memory. The voice falls between verse and prose; an in-between voice. Or a normal voice continually interrupted.

Note: If you read nothing else in Everything Is Now, read “Belling the Lamb”. To put it in tabloid-speak: the shocking tale of murder, madness, and something creepy, in the lives of literary darlings Charles and Mary Lamb.

•

If, in discussing Cliff’s fiction, the fact that many of the characters are gay didn’t come up (or, as it were, come out), it’s because sexual orientation isn’t treated as an issue. A few exceptions: some small-town eyebrow-raising, a brother sent for expensive treatments to cure his condition. Nothing remarkable. That they are gay might be as relevant as their height or dietary habits.

Cliff deals with these and other issues in her non-fiction collection If I Could Write This in Fire. Not with the truncheon of an activist, nor the turbidity of an academic. To far greater effect, she deals with them with poetry, which should come as no surprise, since she talks about — and plays with — language a good deal. There is one actual poem here; the rest of the pieces are — if not always poetic — poem-like. In anything other than a poem (or a Stanley Kubrick film), amorphousness and startling precision would be at odds with each other.

“And What Would It Be Like” is the story of the writer’s relationship with her childhood love, Zoe. It starts: “There is no map,” and yet I believe the poem is the map. It is a map of the topography of class, race, privilege, gender, and the rest of the landscape of colonial Jamaica. It is also a map of the heart that must live there.

There is no map

only the most ragged path back to

my love so much so

she ended up in the bush

…………….at a school where such things were

taken very seriously severely

………………….and

I was left missing her never ceasing

………………….and

she was watched for signs . . .I wanted to be a wild colonial girl

And for a time, I was.

The book takes its name from the essay “If I Could Write This in Fire I Would Write This in Fire”, first published in 1983 in Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology. Re-reading it these many years later, I try to recall how it was received back then: by the critics, the feminists, the post-colonialists, the gay community. But I can’t. Like most of the work in both this book and Everything Is Now, it is a collection of odds and ends that somehow make up a whole. Not whole in the sense of a story wrapping itself together to form a solid, coherent body. Rather, it is whole because so many different stories filter through one voice that what you grasp is a sense of the things that are, the “how” of what happens (happened? is happening?).

And that’s a lot more like life than any linear construct, no matter how beautifully designed. Overall, I am surprised to find I have not wilted under such fast and strong and vulnerable prose. Maybe the tendency to fragmentation is the only way to keep us safe.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, May 2009

Anu Lakhan writes about books and food. She lives in Trinidad.