Zombie occupation

Andrea E. Shaw on Occupy Wall Street’s incursion of the “undead,” and the place of the Haitian supernatural in the American imagination

Occupy Wall Street protester in zombie costume, 3 October, 2011. Photograph by Timothy Krause, posted at Flickr under a Creative Commons license

Zombies are generally understood as beings trapped in limbo between life and death, and have historically been associated with the Haitian practice of Vodoun. They are considered the products of the work of a bokor (magician), who maintains control of the zombie. In his book The Serpent and the Rainbow (1985), later made into a movie, the American ethnobotanist Wade Davis claims that zombification of a living person is indeed medically possible, through the use of tetrodotoxin, a chemical derived from the pufferfish. In Passage of Darkness: The Ethnobiology of the Haitian Zombie (1988), Davis cites a variety of theories about the origin of the word “zombie,” including possible derivation from the French les ombres, or shadows; from jumbie or duppy, Caribbean words for “ghost”; and the Arawak term zemis, “souls of the dead.” However, Davis believes the term is African in origin, most likely deriving from the Kongo word nzambi, which refers to the spirit of a dead person.

Over the past half century, zombies have become an increasingly conspicuous component of American popular culture. According to Shawn McIntosh, co-editor of Zombie Culture: Autopsies of the Living Dead (2008), the term “zombie” was possibly introduced into the American lexicon by William Seabrook’s titillating travel narrative The Magic Island, published in 1929, which “could certainly be considered a pivotal point in spreading awareness of zombies.” Films such as White Zombie (1932), King of the Zombies (1941), and I Walked with a Zombie (1943) further popularised the zombie figure, which rose in particular prominence after the release of George Romero’s 1968 cult classic Night of the Living Dead. Important products of contemporary American popular culture such as Michael Jackson’s music video for his single “Thriller”, the video game series Resident Evil, movies like I Am Legend and Shaun of the Dead, and the television series The Walking Dead are all informed by the myth of the zombie.

This zombie incursion of US borders took an interesting turn in the autumn of 2011, when activists protesting against economic disparity in the United States installed themselves at Zuccotti Park in Lower Manhattan. Now famously known as the Occupy Wall Street movement, these protesters were described by the New York Times as “a diffuse group of activists who say they stand against corporate greed, social inequality, and the corrosive power of major banks and multinational corporations over the democratic process.” Since the start of the “occupation” in September 2011, similar national and transnational demonstrations have erupted in cities across the US and around the globe, including London, Zurich, and Johannesburg. The Occupy movement in the United States was heavily featured in the news media during November 2011. Hostile responses from municipalities and institutions and their respective police forces have led to efforts across the country to uninstall protesters from the various locales where they had set up camp. During this period, newspapers and television screens have been suffused with images of protesters being pepper-sprayed or dragged away, bloodied by the police.

A haunting and memorable feature of these protests has been the choice of zombie attire as the “costume de rigueur” for the Occupy movement. In a massive demonstration in Manhattan on 3 October, activists dressed as corporate zombies lumbered through the city, fake blood oozing down their chins against ashen faces, with mouths stuffed full of fake money. Zombies have also turned up as part of numerous other Occupy protests in diverse locations. Occupy London zombies protested in front of St Paul’s Cathedral; Occupy Sonora zombies in California demonstrated at the local courthouse; and Occupy Toronto zombies marched through the city. There have even been zombie arrests, and on Black Friday (the Friday after Thanksgiving Day in the United States) an Occupy Harrisburg protestor in Pennsylvania was arrested at a shopping mall for refusing to remove her zombie face makeup.

Photograph by Timothy Krause, posted at Flickr under a Creative Commons license

These images, merging death and money, economics and the supernatural, are an intriguing appropriation of elements associated with a Caribbean spiritual practice as part of a trope for analysing US fiscal policies. The politics of representation underlying this symbolism implies that corporations have become ghoulish automatons, devouring anyone in their path. In her book Consuming the Caribbean: From Arawaks to Zombies (2003), the scholar Mimi Sheller identifies a further irony when she explains that the Haitian term for the wealthy is “gro manjeurs,” which translates to “big eaters”. Sheller explains that this term suggests the poor are being consumed by the rich, a parallel to Occupy Wall Street’s efforts to depict corporate greed.

Photograph by Timothy Krause, posted at Flickr under a Creative Commons license

Photograph by Timothy Krause, posted at Flickr under a Creative Commons license

Photograph by Timothy Krause, posted at Flickr under a Creative Commons license

•

In the Caribbean, there is a long tradition of invoking the spirit world as part of a resistance strategy against hegemonic forces. In some cases, elements of the supernatural serve as allies in battle. For example, Vodoun, the spiritual practice often associated with zombies, is reputed to have had a foundational role in the Haitian Revolution, and the Vodoun ceremony at Bois Caïman believed to have initiated the revolt is now legendary. In The Black Jacobins, C.L.R. James explains the ritualistic underpinnings of the revolution when he describes its launch:

their priests . . . chanted the wanga [charm or spell], and the women and children sang and danced in a frenzy. When these had reached the necessary height of excitement the fighters attacked.

The historian Hans Schmidt argues that in Haiti Vodoun has functioned as a “rallying point for mass political action and resistance against foreign domination.” In other instances, the supernatural is employed as a symbolic representation of the corruption plaguing a particular historic moment.

Reggae and calypso repeatedly shape narratives involving supernatural entities and use these narratives to engage the region’s collective social, political, and economic nightmares. The ghoulish bodies in these narratives serve as symbols for collective nightmares, and as the object of conquest in the songs. For example, Bob Marley’s “Duppy Conqueror” narrates the heroic escape of its protagonist from a metaphoric prison, and describes that prison and its underlying political machinery as a “duppy”; hence the hero becomes a triumphant duppy conqueror. The Occupy movement has engaged the image of the zombie in a similar fashion. The movement, which is representative of oppressed peoples in contemporary America (the much-touted ninety-nine per cent), is using the supernatural to discredit the oppressor (corporate America) by designating that entity as undead — as a subject or practitioner of sorcery, which has led to its cannibalistic onslaught on the American economy.

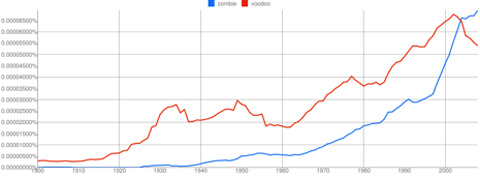

Both zombies and Vodoun have become increasingly popular points of cultural reference in the US over the past century. One way to chart this is using a Google Ngram, which searches for specific terms in a large body of digitised books. (Google defines an Ngram as follows: “When you enter phrases into the Google Books Ngram Viewer, it displays a graph showing how those phrases have occurred in a corpus of books (e.g., ‘British English’, ‘English Fiction’, ‘French’) over the selected years.”) A Google Ngram covering the period from 1900 to 2008 and drawn from Google’s selection of books published in English indicates the exponential increase in the appearance of the terms “zombie” and “voodoo” (the term popularised in the US to define, most often incorrectly, the practice of Vodoun).

Google Ngram showing the increase in popularity of the terms “zombie” (blue) and “voodoo” (red) over the past century in a wide selection of books printed in English. Author’s note: Thanks to Raphael Dalleo, who referred me to blogger Bill Benzon and his post “Zombies Rising” published on 16 October, 2011 on the blog The Valve: A Literary Organ. Benzon’s post gave me the idea to reference an Ngram.

It is significant and in some ways ironic that zombies should become the icon for an “occupation” force, given Haiti’s troubled history with America and Haiti’s own occupation by American military forces from 1915 to 1934. The occupation was preceded by American anxieties over Haiti’s political and economic stability. (According to Hans Schmidt, between 1888 and 1915 ten of the country’s eleven presidents were murdered or unseated by insurgents.) These included concerns about the disproportionate economic influence wielded by Haiti’s small German population, Haiti’s ability to pay its national debt (which some argued was an unfounded worry), and the security of American interests in Haiti; however, it was mostly military strategic concerns that led to the occupation. Schmidt further argues that racist impulses helped undermine the already problematic occupation project:

The generous and even noble narcissist compulsion to bestow American civilisation was stymied by self-defeating ethnocentric prejudices, cultivated during several centuries of domination over Indians and black slaves, which stigmatised the subject peoples as genetically and culturally inferior.

How ironic, then, that almost one hundred years after Haiti’s occupation by the US the “monstrous” figures most closely associated with that island in the American imagination should transgress national borders and find their way to New York to initiate a reprisal of sorts: Haiti’s occupation of America. The protesters are effectively invoking Haiti’s history and culture by way of zombie iconography to mark their stringent opposition to contemporary fiscal policies that have facilitated corporate greed and corruption. This enactment of elements of a Caribbean spiritual practice as a means of commenting on American fiscal concerns presents an unusual dialectic, a peculiar conversation about the Caribbean’s history and culture and the contemporary American economic landscape.

Photograph by Timothy Krause, posted at Flickr under a Creative Commons license. See more of Krause’s photographs of “zombie” protesters here.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, November 2011

Andrea E. Shaw is assistant director of the Division of Humanities and associate professor of English at Nova Southeastern University in Ft Lauderdale, Florida. She is the author of The Embodiment of Disobedience: Fat Black Women’s Unruly Political Bodies (2006) and also a creative writer. She is associate editor of sx salon and a member of the editorial board of Anthurium.