Portrait of the artist as an old man

By Jane King

White Egrets, by Derek Walcott

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 978-0-374-28929-4, 86 pp)

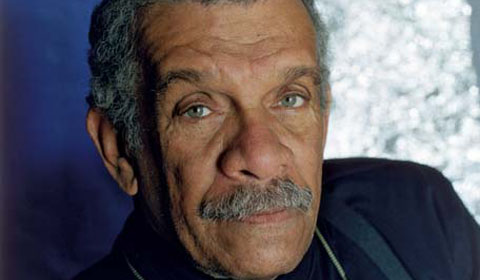

Derek Walcott

2010 has been a terrible year for deaths in St Lucia. Of course we know that death is common — but there are times when folks say, “Basil busy.” 2010 has been one of those years, especially for those of us here who have any sort of connection with the arts. We have lost far too many. Derek Walcott’s sister, Pam, died in Barbados. At home, we lost Pat Charles, Athanasius Laborde, Sesenne Descartes, Sixtus Charles, Francis Tobias, Petronilla Deterville. My mum, Anne King. And too many more. I take a leaf out of Walcott’s book in naming them, as he names some of the many dead. And so it is marvellous this year to have been given a poetic manual that speaks directly, honestly, and clearly to issues of ageing, disease, bereavement, and death. White Egrets of course speaks also of love and joy, those odd flowers that manage to bloom all the more beautifully for being rooted in the awareness of transience that comes when death touches us closely.

One of the judges of the Forward Prize this year (a British poet, and I think his name is Hugo Williams, but I will take a leaf out of one of his unseen books and refuse to find out any more about him) was quoted as saying that he had first come across Walcott’s poetry when he (Hugo, I suppose) was eighteen, had found him (Walcott) a bit “florid” then, and never seen any reason to go back on that. I assume that Hugo and Co. did not actually read White Egrets. It would be hard to describe this writing as “florid.” It is so quiet that at times Walcott himself wonders whether his gift has left him, as some of his detractors seem to have suggested. It hasn’t.

This book has the power and the heft of one of Rembrandt’s late self-portraits. In the latter part of White Egrets, as he visits Amsterdam and “reflect[s] on how soon [he] may be going,” Walcott contemplates his own Dutch heritage —

Silly to think of heritage when there isn’t much,

though my mother whose surname was Marlin or Van der Mont

took pride in an ancestry she claimed was Dutch

— and wonders why he shouldn’t claim that ancestry “as fervently . . . as a creek in the Congo.” And with the quietness of that question, he refers to all the vexed issues of race and ancestry and the Caribbean attitudes to them he once ranted about in chapter nineteen of Another Life. Walcott is fully cognizant of why it is people feel he ought to suppress his Dutch ancestry and prioritise (if I may borrow a bureaucratic word) his African antecedents, but he has reached a point where he is able to look at himself squarely and paint exactly what he sees, without histrionics, without fuss, as Rembrandt was able to look at his every wrinkle and wart and put it down on canvas simply and honestly because it was there. Let others make of it what they may. We may have lost some of the fabulous ranting, but we are gaining a new sort of quiet, sometimes understated clarity. A dignity, even in sometimes embarrassing situations.

Take what he writes about his painting. He has sold paintings, once thought he “had done some more than tolerable,” but suddenly sees the work in his studio as having no “style, just a crass confidence.” He writes of their “scabrous surfaces” and how the grief at this loss of belief “cracked the heart and left it aching.” Later he tackles the same question in relation to his writing. He laments:

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . it’s still incredible the way

the gift abandoned me like a woman I was too old for,

I thought it was the violet that stood up to the armoured car . . .

— worrying now about what he calls “the coarse / exuberance that passed for wit.” In real life, Walcott’s raucous laughter and schoolboy jokes are an endearing exuberance, which has little to do with the careful, delicate choice of words in the poems. It is sad that anyone made him feel even briefly it might be true that his “gift has withered, that there’s little left of it,” and, if that is true, he ought “to abandon poetry like a woman because you love it / and would not see her hurt.”

•

At least since Another Life, Walcott’s books have increasingly been a chronicle of his life reflected on in poetry, a series of self-portraits. Like several of the earlier works, White Egrets can be read as a narrative, the story of a particular period in a life which is on the one hand extraordinary — in that it is the life of a fabulously talented man whose gifts have been recognised and whose recognition has brought him fame, travel, and an experience of wealth — and is on the other hand the story of all of us, male or female, wealthy or not, who inevitably experience bereavement, illness, and the fear of death.

A complicated love story runs through this narrative like a watermark. I have no privileged information here; I can only read what the poet is willing to tell us, which, in the case of his love stories in poetry, has never been very much. Among other things, she is “flat faced,” “there never really was a ‘we’ or ‘ours’,” “there was no ‘affair’, it was all one-sided,” it was all “unrequited,” but the “brown faun that grazed on his heart” provides a lot of the lightness and the beauty of this poetry. The non-affair also serves as a terrible reminder of ageing and mortality. Most reviewers have fastened on White Egrets’ “Sicilian Suite” with its

I’ll tell you what they think, that you’re too old to be shaken

by such a lissome young woman, to need her

in spite of your scarred trunk and trembling hand . . .

Interestingly, “only her suffering will bring [him] satisfaction,” and the poet imagines the funeral of his beloved “with a cortege of caterpillars too gaily dressed” and a blackbird from the Ministry of Culture among other mourners — all birds, butterflies, and worms. In the “Spanish Series” he imagines that

I would sit there alone, an old poet

and you, my puta, would be dead . . .

There is a chapter also for a first love, “Sixty Years After”, in which the two sit, he in his and she in her wheelchair, “in the Virgin lounge at Vieuxfort” — “Virgin” a pun, since that airline does not in fact have a lounge in Vieuxfort separate from non-virgin airlines. At the end of the book, however, on a pier in the orange light of a Caribbean sunset, the poet acknowledges that

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Happier

than any man now is the one who sits drinking

wine with his lifelong companion under the winking

stars . . .

This late self-portrait has an impressive ability to look with honesty on the “scarred trunk and trembling hand,” to look baldly on loves past and to make statements as simple as: “I treated all of them badly, my three wives.” It has a moving capacity to chronicle all the ailments: the diabetes, “the furious itch that raises welts,” the “coughing” that ruined the time in Barcelona, the “whimsical bladder and terrible phlegm,” the irony that is proud of the weight loss that won’t make him “Superman,” will just mean he’ll “need a slimmer coffin” (which, incidentally, with a small measure of his old exuberance, is rhymed with “coughing”).

There are almost certainly those who know immediately the story behind the axe-cheekboned brown faun, just as there are those who recognise the occasions and landscapes in Sicily, in Italy, in Spain, and who visualise exactly what Walcott is seeing when he describes them. I can visualise “lonely Barrel of Beef” and the ciseau birds over it, the causeway down which “the scyther, Basil,” rides, the myriad other St Lucian scenes which make immediate visual sense to me, and make me wonder how they read to others who have never seen them. Does a reference to “lonely Barrel of Beef” make a puzzle of the stanza for those readers, the way the image on the first page, the emperor’s “life-sized terra cotta warriors,” did for me until I looked them up? Googling “Barrel of Beef” gives less clear results.

•

It is a joy to revisit some of the metaphors which those of us who really have been reading Walcott since we were eighteen have followed, as the images thread their colourful way through the tapestry of his poetry, this wonderful series of books that provides the inner story of a life. The birds, the sea, the friends who are dead, and the need to memorialise those who are living (because celebrate them how he will, they will be dead before the poem will) — there are reminders of Yeats here. White egrets like Yeats’s white swans achieve emblematic status in Walcott. The quarrelling stevedores, the shell of the ear, the dark rainy days, the other shore that is Africa (across from Cas-en-Bas, as it was across from that earlier beach with the “Sea Almond Trees”), the parenthetical allusion “(blank printless beaches are part of my trade),” the way landscapes turn into pages (and birds to words, and here, beaks to nibs and back again), the Mediterranean/Caribbean similarities (pointed up here by the visit to Santa Lucia and its visual similarities with St Lucia), the naming of the trees, the naming of the dead and of the living, the stanza that wonders whether Europe is the only proper landscape for poetry (“this is poetry’s weather, this is its true home / not where palms applaud themselves and sails dance in mindless delight” — but the whole book contradicts that argument), the thoughts about Time, about Empire, about the ghost of Empire, the references to ageing and illness . . . There are many more familiar themes and images, and tracing any one of these thoughts, ideas, metaphors through Walcott’s work would easily take an essay of its own.

The references to politicians and enemies are as biographically interesting, of course, as the references to women. There is the internalised enemy who possesses him with its “demonic voice”:

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Like the roar

of applause that precedes the actor with increased

doubt to the pitch of paralysed horror

that his prime is past.

“This man” is the one who makes him feel he ought to “abandon poetry.” Not quite an actual enemy, there’s “that bastard” who looks at the Caribbean and speaks of “the emptiness.” Walcott retains the right to criticise the islands, but is at pains to make clear his difference from Naipaul:

. . . . . . . . . . . . This verse

is part of the emptiness . . .

a genuine benediction, as his is a genuine curse.

There is the political, Roman Catholic, greedy enemy of poem twenty-two, whom Walcott attempts to bless, and whom he sees the island itself in its lasting beauty forgiving, whether or not the poet can:

It is not my heart that forgives

my enemy his obscene material desires

but the flare of a leaf, the dart of a mottled dove,

the processional surplices of breakers entering the cove

as penitents enter the dome to the lace of an altar . . .

This is presumably the same enemy from stanza one of poem five, “The Acacia Trees”, who has destroyed (or collaborated in the destruction of) Walcott’s favourite beach, the one on the causeway to which he used to be driven across the pasture from his house. A beach “print[ed]” with “tiny yellow [acacia] flowers,” until “there were men with tapes and theodolites who measured / the wild uneven ground.”

. . . . . . . . The new makers

of our history profit without guilt

and are, in fact, prophets of a policy

that will make the island a mall . . .

In poetry and in political action, Walcott has often tried to fight the destruction of the wild, natural spaces, the “doomed acres,” which developers in their greed are determined to despoil. Walcott’s morning swim on that doomed beach was a habit well known to us locals. There were those who used to make a special morning visit to the beach so that they could say they had seen him writing under the trees. Here, the poet admits defeat with the poignant simplicity that is the dominant tone of this book, the simple, nostalgic, regretful line: “I felt such freedom writing under the acacias.”

The white egrets themselves appear again and again. In their form as emblems of death I suppose they remind the reader most forcibly of “The Saddhu of Couva”. Here they are clearly established as the tick-eating creatures we know them to be, but in one of Walcott’s lovely puns, they also have a

. . . . . . . . . mythical conceit

that they have beat across the sea from Egypt

with the pharonic ibis . . .

profiled in quiet to adorn a crypt . . .

— their wings “certain as a seraph’s.” Early in the book a “spectral white” egret startles the late Joseph Brodsky while he and Walcott relax beside a swimming pool in St Croix, reminding them both of death, that “the unutterable word was / always with us.” As the book progresses, that unutterable word becomes poignantly, sadly, more and more utterable. The poet occasionally identifies with the egrets in their more corporeal incarnations:

We share one instinct, that ravenous feeding

my pen’s beak, plucking up wriggling insects

like nouns and gulping them, the nib reading

as it writes, shaking off angrily what its beak rejects.

Selection is what the egrets teach . . .

Continuing with the punning references to plays, poems, and death, he later suggests that the egrets remind him to

Be happy now at Cap for the simplest joys —

for a line of white egrets prompting the last word

for the sea’s recitation . . .

Throughout White Egrets we see Walcott’s old fascination with dense language, with puns that bring several meanings together, making an apparently simple utterance in reality very complex. His love of rhyme — sometimes humorous, polysyllabic rhyme — is also apparent throughout the book. There is the odd inverted simile, when for instance a “gale-haired beauty pushes a canto in Dante / open like a glass door.”

The poems in this book move all over the Western world, capturing the poet’s reaction to places often in deft little stories, such as the New York one (poem sixteen), in which for a moment the poet finds himself alone, emerging from the subway as one of the last people left in the world. That horror story is quickly undercut by the more mundane, amusing sort of horror story:

Everyone in New York is in a sitcom.

I’m in a Latin American novel, one

In which an egret-haired viejo shakes with some

Invisible sorrow, some obscene affliction . . .

•

Walcott’s later books have usually had his paintings on their covers. The tone of this book is the grey of its cover. It is the grey of the grudging recognition of death, including his own, in attitudes that range and wander among feelings of protest, as in “It’s what others do, not us, die”; acceptance, as in “with the leisure of a leaf falling in the forest . . . my ending”; and grief. There are many episodes describing raw grief. One of the most beautiful and moving is poem twenty-six, which describes the feeling of looking at the phone numbers of the dead in an address book — and which I will not quote at all, because I would want to quote the whole page. Walcott, as always, feels the desire to get on with the work — because time is passing and the day will come when he will no longer be here to do the work, and because the living whom he wishes to celebrate may not be around to be celebrated if he does not hurry: “Quick, quick, before they all die . . .”

A grey, rainy season book from a poet who once found the island “loveliest in drought.” “The egrets stalk through the rain / as if nothing mortal can affect them,” emblems of eternity, while “friends, the few I have left / are dying,” and sometimes even “the hills . . . disappear / like friends.” These lines at the beginning of the book celebrate “memory” and “prayer,” and the book ends with another rainy season poem, a thirteen-line stanza that harks back remarkably to the In a Green Night sonnet in which Walcott leaves St Lucia for the first time, a sonnet which is repeated almost word for word in Another Life. Here, in a beautiful twist, the image is reversed. In the earlier poems, the poet looks out of the plane window and sees the island getting smaller and smaller, the roads becoming like “twine.” Here he returns to the island through the poem whose page is like a cloud, occasionally hiding the mountains but finally parting, allowing him to see “the whole self-naming island” (the island that he, in Another Life, wanted to name), “its streets growing closer like print you can now read.”

One word from “Adieu foulard . . .”, the original Green Night poem, was changed when the sonnet became part of the end of chapter seventeen of Another Life: in the original, “each mile” the plane put between the poet and the people and island he loved was “dividing us and all fidelity strained / till space would snap it”; in the version incorporated into the longer poem in Another Life, each mile was “tightening” them. White Egrets assures us that the thread of fidelity may have been strained, but could never have been snapped by any space that ever separated the poet from his home. In this book, our icon returns to us, through parting clouds, to a place that, despite its shortcomings, is home, a place where we are humbly glad to welcome him back.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, November 2010

Jane King is a St Lucian poet, author of two collections: Into the Centre (1993) and Fellow Traveller (1994). Her poetry has also appeared in several anthologies in the United Kingdom, and literary magazines in the United States. She is dean of the division of arts, science, and general studies at the Sir Arthur Lewis Community College in St Lucia.