The anthropologist

By Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw

How to Make Love to a Negro Without Getting Tired (originally published in French as Comment faire l’amour avec un nègre sans se fatiguer), by Dany Laferrière, trans. David Homel

(Douglas and McIntyre, ISBN 978-155-365-585-5, 144 pp)

I Am a Japanese Writer (originally published as Je suis un écrivain japonais), by Dany Laferrière, trans. David Homel

(Douglas and McIntyre, ISBN 978-155-365-583-1, 192 pp)

Heading South (originally published as Vers le sud), by Dany Laferrière, trans. Wayne Grady

(Douglas and McIntyre, ISBN 978-155-365-483-4, 216 pp)

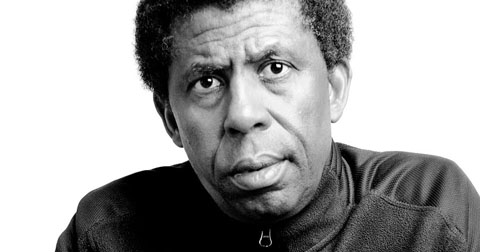

Dany Laferrière. Photograph courtesy Douglas and McIntyre

On my first visit to Haiti in 2007, I remember asking Dany Laferrière whether what I had heard was true: had he decided to stop writing? I think I remember him saying yes, that now he was focusing more on film projects. In fact, Laferrière had been working on several projects, but he was also writing books. I must have been thinking about his interviews with Bernard Magnier, published in a book titled J’écris comme je vis (2000), in which Laferrière had given a clear, even logical reason for deciding to stop his literary projects: he had completed the journey of the “Autobiographie américaine” that began with L’Odeur du café (1991). The writer said he felt tired — “Je me sens un peu fatigué” — and was ready to explore other forms of expression. Laferrière would go on to write a novel called Je suis fatigué, published in 2000.

In his Autobiographie américaine, Laferrière created a writer personage whom he said could survive in the jungles of North America, but also in my opinion able to survive both real and imaginary returns to his place of birth, Haiti: a country that left both sweet and bitter memories; there was the memory of his beloved grandmother, but also the legacy of the terrorising Duvalier regime. His Pays sans chapeau (1996) captures the tenderness and the tension experienced by Laferrière’s writer personage on a return visit to Haiti.

Laferrière is one of the most enigmatic, provocative, and charming writers I have ever met or read. He is unpredictable, save for a trait that few writers escape; what I call an anthropological nature. There are some writers who seldom leave their chosen territory of exploration once they begin to dig. The tools or techniques may vary, but the primary enquiry invested in excavating what they believe is buried can take years, decades, or even a lifetime. For these writers, their creative landscape is determined by this unrelenting curiosity, by their thematic preoccupation or puzzle.

One of these buried puzzles for Laferrière is the question of identity; a word that in a twenty-first-century context has become banal and even liquidated, except perhaps when tackled by the likes of Laferrière, who has often claimed he is a writer and a Haitian, not a Haitian writer. He is also not a Caribbean writer, or a black writer, or a French writer, or a black French writer; and he is not a Canadian writer, although Laferrière has lived in Montreal for many years. This obvious desire to remove or dismiss all the labels is typical of Laferrière. It also explains a title like I Am a Japanese Writer. In fact, in Magnier’s interview, Laferrière says provocatively that he dreams of writing a book with this very title: “Je rêve d’écrire un livre avec ce titre: ‘Je suis un écrivain japonais’.”

The question of identity for Laferrière is not only about ethnicity, culture, and nationality, but also about writing, writers, and the work itself. As a writer who has always been affected by process as much as product — and by that I mean the writer’s methodology and style, as well as the book’s narrative content — Laferrière positions himself as both the writer of the work and its reader. He creates and critiques with a gift of objective distance, but also with the necessary subjectivity to engage in the act of writing. How he identifies his writer personage is informed by these multiple roles.

•

The translators of three recent English-language editions of Laferrière — David Homel (How to Make Love to a Negro Without Getting Tired and I Am a Japanese Writer) and Wayne Grady (Heading South) — have both managed to capture Laferrière’s voice: sardonic, humorous, wily, intelligent, but always sharp and uncompromisingly honest. Conversations exist among the three works, particularly between How to Make Love and Japanese Writer, and Laferrière’s excavations are at times playful and provocative but essentially profound.

When How to Make Love was published in French (in 1985), Laferrière recalls with bitterness and amazement, “nobody believed it was written by a black man. They said, Whoever wrote it writes almost like a black. Everyone was sure it was written by a white. A black couldn’t write like that they said.” This book, written in fact by a “Negro,” was compared to other writers who wrote as fearlessly (Charles Bukowski, Jack Kerouac, Henry Miller, and James Baldwin). According to the Haitian newspaper Le Nouvelliste, the book showed that Laferrière was “without respect for any kind of sexual morality”; for the Montreal newspaper La Presse, How to Make Love had a “terrorist side to it . . . a little grenade designed by a conscientious, clever demolition expert.” The Hamilton Spectator saw the book as being “calculated to offend both blacks and whites.” It was obvious that the critics did not know where to place this writer from Haiti who wrote in an almost-black way. An original voice had emerged, one that did not have a traceable ethnic literary origin; it was indefinable.

The plot of How to Make Love is fairly straightforward. The narrator, a young Haitian man, migrates to North America and ends up living in a grungy apartment in the slums of Montreal with a black Muslim jazz aficionado roommate named Bouba. The two men spend much of their time listening to jazz icons, drinking wine, eating cheap food, reading, discussing Kant, Hegel, the Koran, Freud, and Allah, and having sex with several white Canadian women who get tagged with titles like Miz Literature, Miz Sophisticated, Miz Beauty, or Miz Piggy. Bouba seldom leaves his bed; it is where he prays, eats, professes, and has sex. We see the world outside of the apartment through the narrator’s wanderings through the streets of Montreal. He is writing a book about his experiences, one that he hopes will get him fame and fortune.

Laferrière worked as a journalist when he lived in Haiti, and his novels have a journalist’s eye for detail that allows him to set up a scene effectively. The details are not symbolic, nor do they give balzacien psychological insight; they pretend to do nothing but describe the object or person in the narrator’s view. Laferrière’s narrator approaches old themes in a similar fashion. How to Make Love revisits the subjects of history, slavery, race, racism, class, and the definition of the Negro with a similar distance. As the provocative title suggests, the idea of the Negro as a great lover is both embraced and dismissed. It is reflected in the behaviour of the narrator and deflected by his desire to expose its absurdity. For example, at the end of the novel the narrator is interviewed about the success of the book he has written, titled Black Cruiser’s Paradise. The interviewer accuses him of not liking women; the exchange goes like this:

“I read your book and I laughed, but it seems to me you don’t like women.”

“Negroes too.”

“But you do go a little far . . .”

“. . . Let me point out that for all intents and purposes there are no women in my novel. There are just types. On the human level, the black man and the white woman do not exist. Chester Himes said they were American Inventions, like the hamburger or the drive-in . . .”

The interviewer also notes that in this novel the blacks do not “appeal to Africa.” The narrator replies that their faith belongs to Islam, that their culture is European not African, “that Allah is great, but Freud is their prophet.” Through a provocative dismantling of Western society’s carefully constructed image of the Negro, How to Make Love illustrates how easily classifications depersonalise to create types rather than individuals.

Although I Am a Japanese Writer (published in French in 2008) was written more than two decades after How to Make Love, the two books are clearly part of the same conversation of definitions and identifications. Once again the protagonist is a writer of Haitian origin living in Montreal, who has been given an advance based on the title of his next book alone: I Am a Japanese Writer. “Ten thousand euros for five little words.” The problem is that the writer is suffering from writer’s block and spends much of his time with a group of young sexually adventurous Japanese girls, lead by the beautiful pop star Midori. The writer is also a great fan of the seventeenth-century Japanese poet Basho, whose works are always with the writer. Basho’s poems become another voice in the text; they allow the writer to compare contemporary Western culture with a more elegant older world.

The novel’s plot becomes more complex as the title of the unwritten book begins to take on a life of its own; and even more complicated when the writer actually declares that he is a Japanese writer. This statement has destabilising cultural effects, particularly for the Japanese; copycat cases emerge, as a Japanese officer declares on television, “I am a Korean soldier.” The writer is also spied on by members of the Japanese embassy; they see a clear and present danger if national identity can be claimed or disclaimed in this manner. If How to Make Love creates a binary structure of Negro type versus non-Negro type, Japanese Writer is a kaleidoscopic image of identity; it is colourful, fractured, varying, blending, and never stable. It allows a writer born in Haiti and living in Montreal to identify with Japanese poetry enough to make it part of his identity kaleidoscope. Naturally, Laferrière is always playing with the absurdity of it all. As the writer protagonist says at the end of the novel: “It’s good to write a book, but sometimes it’s better not to write it. I was famous in Japan for a book I didn’t write.” The book is an imaginary creation, as is his Japanese identity. But ultimately it points to a writer’s landscape, a subject that the writer-narrator discusses in the penultimate chapter. Here the writer’s voice takes on a rare, transparent quality that exposes and explains why in a literary landscape Basho and himself are brothers — primarily because they both share a belief in art:

Basho didn’t look at the landscape like a geographer. He perceived only its colours . . . Basho acknowledged but one master: landscape . . . As for me, nature puts me to sleep. The peasant disappears into the landscape. His song is the beginning of art . . . I watched their show and thought that people of the earth are the same everywhere . . . Caught inside their songs and rituals. Basho sought to penetrate the secrets of this obsession. He believed the origins of poetry were to be found there.

The writer, like Basho, is a traveller, and this transience allows him to inhabit imaginary worlds where nationalities do not matter.

•

Heading South is a departure from the two previously discussed novels. It is a reworking of several short stories previously published in La Chair du maître (1997) and adapted into a 2005 feature film by the director Laurent Cantet, starring Charlotte Rampling. The novel is set in Haiti in the late 1970s, approaching the last years of the Duvalier dictatorship. Unlike How to Make Love and Japanese Writer, there is no writer personage voice; instead there are multiple voices who take us into the world of young Haitian artists, musicians, prostitutes, hotel owners, and six middle-aged American women who have come to Haiti for new adventures, but mainly to escape their sterile lives in the north.

These women are bewitched by young, beautiful Haitian boys, who are paid to have sex with lonely tourists. The women’s testimonials reveal the many ways in which their views of Haiti and Haitians are shaped by ethnic stereotypes, hypocrisy, objectification, and ignorance. Ellen, a fifty-five-year-old professor, describes Haiti as a “dung heap”; still she cannot understand why “dear God, did you plant, in this dung heap, a flower as radiant as Legba.” Legba’s name has great significance in Haitian Vodou tradition, as the spirit of the crossroads. But the Legba of Heading South loses his power, and at the end of the novel this most beautiful of the boys is found dead on the beach. The murderer is never clearly identified, since Legba’s beauty and charm attracted both men and women, provoking jealousy and rivalry for those under his spell. The tragic outcome for the young man underscores the harsh reality of the sex-trade in Haiti, where death is always a possible outcome.

Through the American characters, Heading South tackles the question of exploitation and the neocolonial foreign presence in Haiti. Apart from the middle-aged women, there is also Sam the businessman, ready to exploit the dire economic conditions of a family-owned hotel about to go bankrupt. Sam is described as “a vulture only seen when something has already died.” The American consul Harry gives visas in exchange for sexual favours from young Haitian girls. In Haiti, Americans have the power to buy literally anything they like, both property and people. The history of this American exploitation of Haiti is recalled by Albert, the Haitian maitre d’hôtel at the beach resort where the women stay. Albert’s father fought against the Americans during the first American Occupation from 1915 to 1934, which led his father to believe that “whites were lower than monkeys.”

Heading South is not stylistically inventive, nor does it have the enigmatic, provocative power of How to Make Love and Japanese Writer. The treatment is more filmic, with short scenes rather than chapters. What Heading South exposes is Laferrière’s range through this exploration of exploitation, dependence, and neocolonialism.

These are but three of this prolific writer’s fifteen novels. I am forced to admit that there is no real conclusion to offer when faced with an enigmatic figure like Laferrière; he may too easily deflect my reflections with his unpredictable, original voice. Perhaps all I can hope for as a Laferrière reader is that his anthropological nature keeps him digging.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, November 2010

Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw is a senior lecturer of francophone Caribbean literature at the University of the West Indies, St Augustine. Her recent publications include two co-edited collections of Haitian essays, Reinterpreting the Haitian Revolution and Its Cultural Aftershocks (2006) and Echoes of a Haitian Revolution: 1804–2004 (2008). She published her first collection of short stories, Four Taxis Facing North, in 2007.