Boom generation

Christopher Cozier on Dean Arlen’s Cape Town Chronicles

We Are Forced to Speak to Kings Because of their Guns (2006), by Dean Arlen; mixed media, 85 x 108 cm. Image courtesy the artist

Dean Arlen visited my studio with a series of poster-size digital printouts on vinyl. He dropped a thick roll of them onto the floor, saying, “Hey, Chris, check dis . . . What you think?” Was he asking about the scale, the quantity, the imagery, or just the gesture of unloading all that “stuff” mentally and physically? There was little to say at that point. We began to look through the printouts one by one. It was like looking through a collection of maps that narrated locations not actual or known but felt.

Placed before me were enlargements of mixed-media collages and markings from the pages from his personal notebooks, produced while he was in Cape Town. Arlen had joined the list of Trinidadian artists who have produced bodies of work in and about places like southern Africa. These works have embarked on a new axis of comparative investigations between us and other southern locations, and what some have called “postcolonial” cultural experiences.

In these enlarged notes, the artist juggles a range of associative devices, whereby coloured shapes, expressive marks, images rendered and collaged, as well as texts, operate within the same symbolic field. It becomes clear that expressive desire and symbolic arrangement are improvisational; so pictorial or compositional resolve is not a burden or an aspiration. One might speculate that it appears to have been deferred, as it may imply or threaten to enforce a false sense of knowing and a sense of conventional order, as if all is well in the world. This work does not offer consolation.

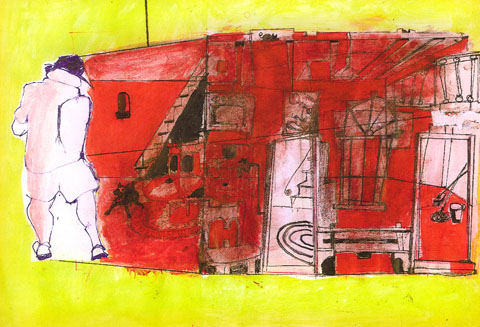

Shabeens/Girls/Men (Township Friday) (2006), by Dean Arlen; mixed media, 86 x 108 cm. Image courtesy the artist

An image that sticks in my mind is of a stark condominium-like courtyard space with lawns and anthropomorphic characterisations. Who are these people? Are they the new global consumers of suburban comforts? They are not faux Egyptian representations, or the usual ancestral indicators, or even the carnivalesque. They express discomfort, and are more reminiscent of a scene from a 1930s surrealist film. In Arlen’s world, these characters move between the suburban sprawl of cities like Cape Town and west and east Port of Spain. On the surface, they may appear united by their economic prowess in occupying such spaces, but they seem alarming and distorted to us, and perhaps even to each other. Arlen often expresses a conflicted relationship to suburbia, and even a romantic reading of the rural:

Suburbia for me is a middle class-ness, and represents all that is wrong with our country . . . tasteless and copycattish, as opposed to the ruralism which generates culture.

Perhaps it may be useful to see all of this as a metaphor for the pressures to secure respectability through being an efficient and fastidious consumer, which is now being advertised as a new form of cultural production. As an artist, Arlen looks to the opposing proposal, that of being a producer or innovator in the traditional or national “culturalist” narrative. It is obvious that these categorisations are polemic, as the artist is working within the popular modes of graffiti and seeking its directness and immediacy.

Arlen sees himself, then, as betrayed by these expectations, or trapped within a new space — perhaps one that became more widely possible in the post-independence era? There is a sense of homelessness, of discomfort and conflict, but the suburb is the only space Arlen knows. So what is he to make of this new landscape of success? It is with these same eyes that he navigates South Africa.

D Marginalisation of Dominance (2006), by Dean Arlen; mixed media, 87 x 108 cm. Image courtesy the artist

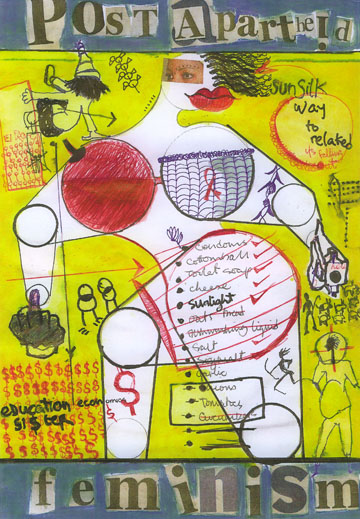

Arlen’s system of signs aspires to convey the customary wit and irreverence of graffiti. A character in a Mickey Mouse hat, smoking a long pipe, is placed next to the words “Zuma is a Mama” (Jacob Zuma, deputy president of the African National Congress and former deputy president of the Republic of South Africa, was at that time charged with rape and corruption while in office. He was later freed on both charges). In another work with a screaming gargantuan figure, we see the words “speak to the King and Queen (they) have no guns”. A Basquiat-like crown (via the logo of the Visual Arts Environment, the experimental independent study programme founded by Trinidadian artists Edward Bowen and Steve Ouditt) sits on the head of another bloated figure with its back to the viewer. Ranks of little generic house shapes symbolise government-provided housing developments and imply the discomfort of the economically displaced, who also face new, unfamiliar social relations and environments. Bottles in rows may imply wanton consumer excess and self-indulgence. One text says “for prick call 212”; another says “acid rain and aspirin.” We see a tractor moving trees and a hillside.

Although they sit randomly on expressive fields of modulated and direct colour application, you cannot escape the ideological construction of these spaces and their inhabitants in Arlen’s work. The women are reduced to conventional, anxious male diagrams, and the men similarly. Whether they are emasculated or dissected, these diagrams seem to map out gender relations and representations in a highly reactive manner. Perhaps the artist is speaking with many voices apart from those of his own immediate circumstances, but also from the heightened awareness of being placed in another social context?

In my first interview with Arlen in the mid 1990s, he asked through one of his works, “Why talk if you could paint words?” His layered surfaces and mixed messages became his way to visually convey the range of voices and concerns expressed at a given moment in his extended world, in which the house or home is integrated into a larger proposal of domestic space:

Domestic space is the block, the rumshop, Woodford Square, d backyard, or any space where a community gathers.

However, there remains a sense of being outside the frame or structure — be it the local art market, the gilded framing of our assumed true tropical selves, or esteemed spaces like our museums, which further frame or validate the tropical as a site. One of Arlen’s earlier presentations occurred on the pavement outside the National Museum in Port of Spain, connected, with permission, to the fences around the building. As in one of his later drawings, he was turning the structure inside out and integrating it into his larger idea of public and institutional space.

Conceptually and stylistically, it is difficult to speak about the work of Arlen without referring to the Visual Arts Environment dialogues, which took place in the late 1980s. In that studio and process, interactions came into being that impacted on an entire generation of artists who were looking at expanding the visual vocabulary as well as the methodology and reason for visual expression. By saying that, I do not mean that these artists were simply receptacles of the analytical stances of Bowen, Ouditt, and the other artists that participated in that dialogue. Rather, they found an enabling space in which they had permission, or were encouraged and supported, to think and make work in challenging ways.

In the early 1990s, Ozzie Merrique, then a member of the rapso group Homefront, suggested that they, “the Boom Generation,” should give themselves a chance to “play themselves.” Subsequently, rapso performer Ataklan further suggested that “when it comes to roots and culture, everybody is a member — come in.” In this early recording, “No Chorus”, he stated that he had not written the chorus as yet, implying that the rules of the music game were not pre-set or fixed, but, regardless, he could still operate — “dat doh mean I can’t jam and fete.” The intro to “No Chorus” asked incredulously, “How you mean that I can’t come in?” Dean Arlen’s work is asking questions alongside a particular generation of cultural producers, but through his own medium.

Urban Suburban & Rural There Was a Hole in Runaway (2006),

by Dean Arlen; mixed media, 108 x 85 cm. Image courtesy the artist

The contemporary space in Trinidad is really a space of possibility for newer relations and discourses in the society, one that is either menacing to those in authority, or of no use at all. The formation of Caribbean Contemporary Arts (CCA) and the recent Galvanize project again ask these questions by bringing together diverse practitioners who would customarily be left out of conventional narratives about nation and culture.

Since the 1980s, the Trinidad art world has expanded significantly, allowing new dialogues and ways of working that are yet to be understood or even seen by our public. Contemporary art is not a rupture from tradition, but an ongoing attempt to keep the cultural dialogue truly open. More and more tropical scenery and feathered bikinis will not help you understand that quiet moment between you and an anonymous gunman on the East-West Corridor.

In Arlen’s past work, the diagrammatic could be linked to a range of previous investigations of representation in this context. The most obvious would be the codifications of Edward Bowen, who often takes the house shape as a parody or as a codification of local pictorial convention. It was either a sign symbolising a journey through personal space, family conflicts and negotiations, or just a form for his investigations of mark-making, but never a record of a particular or immediate site — it said, you want house, well take house, and all that comes with it.

For Steve Ouditt, it was a conceptual sign — sometimes an industrial warehouse, a barrack house, or cow pen, which all unfolded or expanded into his Creole Processing Zone diagram of a sociological condition or conditioning. For other practitioners, it has been the location of feminist reflections about the relationship between the private and the public and the meaning of the domestic world. In Arlen’s case:

The house shape for me is a metaphor for community. It is where we learn our first thoughts on life, grounding principles, morals, etc. It is loaded with gender politics and power plays, sibling rivalry, love, hate, sex and nature.

I am not claiming to understand Arlen’s work, but I appreciate and support his “hunt” in the mapping out of our social space. For either of us to claim an understanding, much less an arrival at any conclusions at this point, would be to miss the point of his process. I simply want to thank him for continuing to share with us his unpacking of all this “stuff.”

Womenism Post Apartheid (2006), by Dean Arlen;

mixed media, 109 x 82.5 cm. Image courtesy the artist

•

A version of this essay was published in the catalogue of the exhibition of Dean Arlen’s Cape Town Chronicles, held at the National Museum in Port of Spain, Trinidad, in December 2006.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, February 2007

Christopher Cozier is a Trinidadian artist and writer. He has shown his work in numerous solo and group exhibitions in the Caribbean and internationally, and he has published a range of essays in journals and catalogues. He is currently a research fellow of the University of Trinidad and Tobago.