National affairs

By Annie Paul

The Devil’s Currency (2006), by Michael Franklyn Elliott; image courtesy the National Gallery of Jamaica

The 2006 Jamaica National Biennial — which ran at the National Gallery in Kingston from 3 December, 2006, to 10 March, 2007 — was a good survey of what is going on, art-wise, in the nation of Jamaica and its diasporas. Its ambit is the opposite of the better-known biennials of the world, which are international in scope. In contrast, the Jamaica Biennial is targeted “at Jamaican artists, both home and abroad, and foreign artists resident in Jamaica.” The National Gallery’s Annual National Exhibition (inaugurated in 1977) was changed to a biennial show in 2002. Other than this change of frequency, the exhibition remains largely the same, according to the curatorial team: directed at local artists and audiences. “In this sense our Biennial is a true National Biennial.” The sentiment is expressed with a certain pride, as though to be national in scope is an admirable thing.

Fortunately, the curators’ interpretation of “national” is generous, and not tethered to geographical boundaries. Increasingly, the National Gallery has been reaching out to artists in the diaspora, a welcome move, because the inclusion of artists “practicing and exhibiting in the international arena” is just the shot in the arm the moribund Jamaican art environment needs.

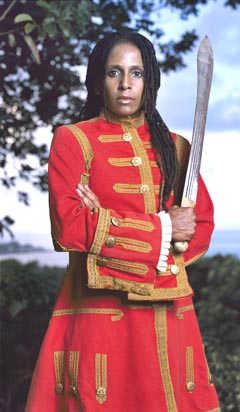

One such artist, whose work dominated the 2006 Biennial, was New York-based Jamaica-born artist Renée Cox. She is perhaps best known for Yo Mama’s Last Supper, the cause of much controversy at the Brooklyn Museum some years ago, when New York mayor Rudolph Giuliani threatened to close down the museum unless the photographic work (depicting the Last Supper, with a naked Cox presiding over the table in the place of Jesus Christ) was removed from display.

Cox’s installation Queen Nanny of the Maroons won the Aaron Matalon Award given for “a particularly outstanding contribution to the biennial.” In the Nanny of the Maroons series, she stages herself in various roles, starting with Nanny herself, and moving on to a prim and proper-looking schoolteacher surrounded by schoolchildren, the fabled River Mumma folklore character, and a warrior peering out through a dense thicket of undergrowth, among others. There was also a stunning series of photographs of Maroon subjects from which the artist withheld her presence. Cox’s impulse is fundamentally redemptive, as she explained in an interview with Jonathan Greenland, director of the National Gallery. “One of the things that I was very interested in from the very beginning was making images that are visually seductive — they bring the viewer in — but they have a message. I don’t want to sound like a 1960s revolutionary, but this message is usually to give back a form of self-love.” Who better to do this than Cox, considered by many to be a black Narcissus in the flesh?

Detail of Queen Nanny of the Maroons (2006), by Renée Cox; image courtesy the National Gallery of Jamaica

In general, the diaspora artists’ work tended to emphasise the anaemia of the local art-world, whose offerings appeared positively provincial in comparison. Placing the work of two Silver Musgrave Medal awardees, Laura Facey and Margaret Chen, in the large space at the entrance didn’t work. Of course, size-wise they couldn’t have gone anywhere else, and one understands the dilemma of the curators, but to be greeted on entry by sculptural works by Chen that one has seen too many times over the years wasn’t exactly stimulating. Isn’t it time to retire the tediously literal Cross-Section of Portal, a large brown vagina dentata sporting a ghostly imprint of a face? Was nothing else available?

Trying to make a hasty escape from Chen’s baleful assemblages, you could easily have overlooked Facey’s beautiful carvings from her 2006 show The Everything Doors. Her subtle yet powerful Blood of Zinc, a rendition of two sheets of zinc carved out of mahogany, poetically references the living conditions of the region’s underclasses.

In the little foyer under the gallery’s staircase, Michael Hayden Elliott’s monochromatic work on aluminium simply titled Independence portrayed a charming vision of the “rural other” free of the usual clichés. In centre foreground, almost spot-lit, stands a little girl with a doll under one arm, while behind her is a stone cottage with another girl looking out of a window; to one side of the house stands an adult couple.

I am more familiar with the larger-than-life-like paintings of Elliott’s son, Michael Franklyn Elliott, whose close-up, in-your-face image of bullets, The Devil’s Currency, excited almost universal approval, and was said to be the most popular painting in the show. I thought at first that the title was too slick and glib, but it did provoke a series of related thoughts or questions, especially after I heard a newsreader describe a scenario in which police and criminals were “trading bullets.” One hears, for instance, of spent or unspent bullets. Why do bullets and shells evoke these tropes of commerce? In other works, Elliott typically focuses on close-ups of piled-up vegetables and fruit (okra, breadfruit, star-apples) or fish, such as you would find in a country market; in this painting he treats bullets in exactly the same manner.

Fundamentally related, though somewhat more sophisticated in both treatment and concept, was Bryan McFarlane’s Unexploded Ordinance Nesting with Egg, featuring a heap of black and white cannonballs expressively rendered in oil on canvas. McFarlane is one of those diaspora Jamaicans I mentioned earlier, as is Peter Wayne Lewis, whose fluid visual explorations of jazz produce rhythmic works of great beauty.

Albert Artwell, one of Jamaica’s more established “intuitive” artists, made his presence felt with his magnificent oil-on-board 33 1/2 Year Story of Christ. Joseph Brown, another self-taught artist, added an innovative note to his Canoe Boat by making some of the carved figures seated in the boat detachable, little carved objects in themselves. Rani Carson’s Afghanistan on Japanese TV framed Osama bin Laden and one of his deputies in an oddly pretty pastel-coloured landscape. Bernard Hoyes’s black and white etching Candle Light Vigil superbly played with light and shadow, filigreed hands forming a pattern of dark against the glow of the mourners’ candles.

Stafford Schliefer’s painting of Marcus Garvey in comic-book colours gave the heroic figure a playful, pop quality. Also a self-taught artist, though never classed with the intuitives, Schliefer continues to be innovative, never churning out the same set of visual statements. Likewise, the fizzy creativity of David Marchand expressed itself with a large Coca-Cola bottle surmounted by a smaller upturned soda bottle, the entire assemblage intricately painted in black and white and titled Cokehead.

In Out of the Urge to be Obvious, Allison Perkins proved that you don’t need to produce gigantic, serious-looking objects to raise interesting questions. On a series of white boxes, each about one and a half inches square, she delicately placed visual equations and propositions, such as a horizontal black line dissecting the white surface with a handwritten caption: “line drawn from left to right.” Perkins revives the delicate form of art-making introduced to Jamaica in the 1990s by Nicholas Morris, now resident in Germany.

Other artists worth noting were Andrea Haynes-Peart, with Patty Line, focusing on differently shod feet waiting in a line; Christopher Irons, whose work, as usual, referenced state-sponsored brutality in Jamaica; Paul Smith, with his grotesque crucifixes; and Michelle Eistrup, with the video installation Looking Back, Looking Forward, Post-Colonial Re-Visitations.

One artist whose work excited a lot of comment in the print media was Camille Chedda. Her mixed-media-on-plastic assemblages starkly depicted human figures with their heads in suffocating black plastic bags. They were accompanied by a video called Project Black Scandal Bag, which seemed to disturb those who wrote about it in the press.

But, overall, the 2006 Biennial failed to impress, despite the wonderful opening, which was an event in itself. I realise the difficulty of imposing any curatorial focus on a show as large and eclectic as this, but, even so, this latest Biennial seemed to signal the exhaustion of the singular curatorial vision that has dominated Jamaica’s National Gallery for the last thirty-odd years. It’s clearly time for a regime change — but when and how? And perhaps it’s also time to stop thinking in national terms, and reach out not only to the diaspora but the whole Caribbean region?

Crucifixion (2006), by Laura Facey; triptych, cedar and oil paint, 147 x 78 inches; image courtesy the artist

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, May 2007

Annie Paul is head of publications at the Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies (SALISES) at the University of the West Indies, Mona, and managing editor of the journal Social and Economic Studies.