To make you see

Garnette Cadogan on V.S. Naipaul’s non-fiction

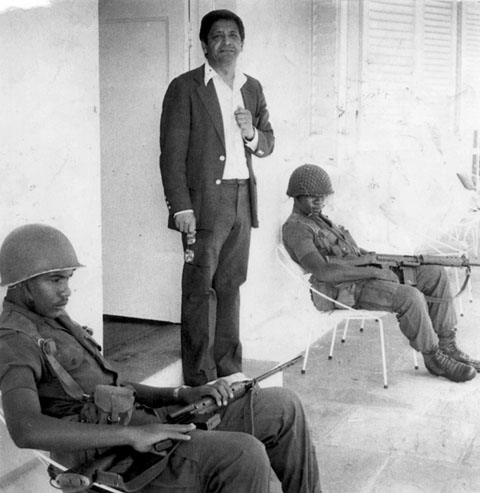

V.S. Naipaul in Grenada, soon after the US-led invasion; November 1983. Photograph courtesy Trinidad Publishing Company Limited

The problem of exile is that it becomes increasingly hard to go home. You might eventually be able to return physically, but not to the country you left. Too much will have happened in the meantime. Those who stayed behind will have changed, but the exile, because of his peculiar experience, will have changed even more, marked by exposure to an alien world.

— Ian Buruma, Bad Elements: Chinese Rebels

from Los Angeles to Beijing

V.S. Naipaul, long celebrated in the Caribbean for his fiction, especially his magisterial novel A House for Mr Biswas, receives in comparison scant attention — reading attention, anyway — for his remarkable body of literary non-fiction. Judged by the reaction of Caribbean academics, critics, and the reading public, one could be misled into believing that the novel is Naipaul’s exclusive creative métier. Yet a mere perusal of his non-fiction reveals observations no less acute, portrayals no less precise, and scenes no less finely drawn. Indeed, the same literary tics prevail: a deceptively simple, efficient prose, wielded like a machete one moment and controlled like a scalpel the next; a measured pace punctuated with disarming aperçus and propelled by irony; a predilection for autopsy over elegy; and the proud, skeptical observer and inert participant standing at the crossroads of a recidivist colonialism and flailing post-colonialism: the weight of history pressing on the personal. In fact, Naipaul’s letters, novels, and travelogues are of a literary whole. In Reading and Writing: A Personal Account, he says:

So, as my world widened, beyond the immediate personal circumstances that bred fiction, and as my comprehension widened, the literary forms I practiced flowed together and supported one another; and I couldn’t say that one form was higher than another. The form depended on the material; the books were all part of the same process of understanding.

Why, then, the neglect?

Certainly, part of what makes Naipaul such a compelling writer is his ability to penetrate and excoriate (and with deceptive ease at that). “These islanders are disturbed,” he wrote in a 1970 New York Review of Books essay, “Power to the Caribbean People”. “They already have black government and black power, but they want more. They want something more than politics. Like the dispossessed peasantry of medieval Europe, they await crusades and messiahs.” In some quarters, the wound is still raw.

Truth be told, in far too many cases the painful comments remain true. Written about Jamaica about a quarter-century ago, this reads like a recent dispatch:

In Jamaica my diary entries grew shorter and shorter . . . There was nothing new to record. Every day I saw the same things — unemployment, ugliness, over-population, race — every day I heard the same circular arguments.

Not surprisingly, then, Naipaul is branded a harbinger of unfair criticism and distorted analysis, the colonial camouflaged in postcolonial garb.

But to settle at this conclusion is to miss salient qualities of his non-fiction. Joseph Conrad, whose mark he bears, captured its essence. “My task which I am trying to achieve,” Conrad wrote, “is, by the power of the written word, to make you hear, to make you feel — it is, above all, to make you see.” So too with Naipaul: he makes us see, really see, with an unsentimental eye; understanding follows close observation. As he says in Finding the Centre: “The reader will see how the material was gathered . . . All that was added later was understanding. Out of that understanding the narrative came.” A narrative of scrupulous observations, populated with rounded characters who speak for themselves.

Although, to be fair, Naipaul sometimes blunders by making individual opinions represent a general belief or state of mind. At his worst, he subsumes his characters’ views in his quarrels with history, fate, and the people made fools of by them. A 1972 New York Review of Books essay on Argentina, “The Corpse at the Iron Gate”, which berates the country as a place without history, reveals a Naipaul who listens but doesn’t hear. Writing about Borges, he makes a claim that might as well have been about himself: “Like many Argentines, he has an idea of Argentina; anything that doesn’t fit into this is to be rejected.” A careful read, though, of Naipaul’s essays — especially on the Caribbean, the American South, and India — offers remarkably tender, attentive portraits.

Naipaul’s father once instructed him by letter to “find the centre,” and it’s no exaggeration to say that much of his writing, fiction (for example, The Enigma of Arrival, Half a Life) and non-fiction (Finding the Centre, India: A Million Mutinies Now, to name only two), testifies to that quest. In Finding the Centre, he writes: “The people [on the Ivory Coast] I found, the people I was attracted to, were not unlike myself. They too were trying to find order in their world, looking for the centre; and my discovery of these people is as much part of the story as the unfolding of the West African background.” It is the spirit of Conrad wed to that of his father that suffuses his writing. His father, after all, also wrote to him, “Only see that you have succeeded in saying exactly what you want to say — without showing off; with utter brave sincerity — and you will have achieved style because you will have been yourself.”

Being yourself. Indeed, Naipaul’s writing is, if nothing else, a partial self-portrait, a revelatory slice of a man who is by turns curmudgeonly, proud, and angry (even bitter) — yet also tender and empathetic. He never fails to describe his relationship to his characters, nor his fears, dislikes, foibles, prejudices, and misbehaviour. His stance, however, is not colonial: no amused gaze or haughty scorn, to be sure; no patronising or mockery (snapping irony, though). His detractors, many of whom have only read excerpts from his non-fiction or paid too much attention to his public wallops, are likely to think the severely critical author of An Area of Darkness is the same writer in India: A Million Mutinies Now. Well, yes and no. Unfortunately, we have allowed the Naipaul who doesn’t suffer fools or fans gladly to obscure the more compassionate Naipaul found on the page. True, his words provide more fire than balm, but his self-criticism saves him from false empathy and sentimentality, subjecting him to the same heat turned on his subjects.

“Fiction had taken me as far as it could go,” Naipaul says in Reading and Writing, adding, “There were certain things it couldn’t deal with.” Writing non-fiction, it turns out, was his way of discovering the world and himself. In Finding the Centre he says, “over and above their story content, both pieces [a draft of an autobiography and a narrative on the Ivory Coast] are about the process of writing. Both pieces seek in different ways to admit the reader to that process.” Naipaul has travelled as an exile, in constant argument with history and the present, combating his self-exile and the self-contempt of others by paying close attention to the rhythms of time and culture, and recording it in his inimitable voice. In the end, we can say of his writing what he once said of Richard Jeffries’s: “[His] people carry so much knowledge and experience that they often contain whole lives.”

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, August 2007

Garnette Cadogan is a freelance writer. He was born in Jamaica and lives in New York City.