What Vidia saw

By Brendan de Caires

A Writer’s People: Ways of Looking and Feeling, by V.S. Naipaul

(Picador, ISBN-10 0330485245, ISBN-13 978-0330485241, 194 pp)

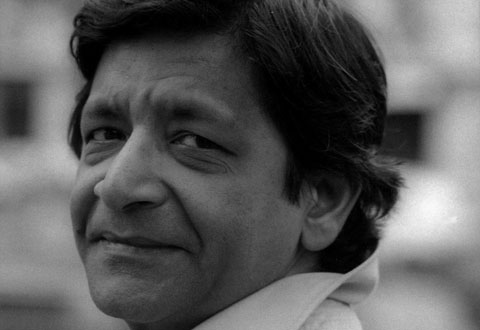

V.S. Naipaul. Photograph courtesy Picador

The enigma of the title is this book’s first surprise. Many of his people remember Naipaul comparing them to “monkeys, pleading for evolution,” and describing the West Indies as “simple, barbarous, and limited.” A few of us assumed he had left us behind forever. Perhaps some of it was picong and the days of provocation are past; perhaps Trinidad’s “Year of Sir V.S. Naipaul” has worked its magic on the old man, and he is ready for a truce. Alas, no. Sir Vidia is not going gently into his good night. This book bristles with spite, liberally dispersed among friend, rival, and foe. Derek Walcott, Anthony Powell, Nirad Chaudhuri, even Gandhi, Flaubert, and Virgil are weighed and found wanting, none of them quite able to sort out the correct “ways of looking and feeling” from ones that are merely expedient.

Whenever a new book is due, Naipaul makes himself notorious. Each time his squibs get a little louder. A short while back, we learned that James Joyce had an “amoral style” and was “not interested in the world”; more recently, the “dreadful American” Henry James was dispatched as “the worst writer in the world.” Up to now, Naipaul has had the good taste to keep the mischief-making conversational. In that sense, A Writer’s People is a real departure from what has gone before. It is also, in parts, Naipaul’s gravest literary misjudgement since getting rid of the novels which Paul Theroux had autographed for him. That oversight provoked Sir Vidia’s Shadow, Theroux’s deliciously nasty memoir. This time, however, the curmudgeonly Naipaul is an inadvertent self-portrait. After such knowledge, what forgiveness?

Many readers have shown little patience with his cattiness. Andrew O’Hagan interrupted an obituary for Norman Mailer in the Telegraph to lament how Naipaul’s “recent book . . . seems to feast on other writers’ failures and infirmities, making out that nobody’s dismal work could possibly stand comparison with the great Sir Vidia’s . . . [the book] will, I imagine, permanently lower people’s sense of Naipaul’s quality. He has performed a literary task very much against himself . . .”

In Kenneth Tynan’s re-readable diaries, an English playwright says of an actor, “He’s his own worst enemy — but only just.” The same could be said of Naipaul.

•

A Writer’s People opens lyrically with a passage that sets us down in his “grandmother’s house in the Woodbrook area.” There, Young Vidia learns to observe the street from the privacy of a fern-shaded verandah. The first page is vintage Naipaul: four commas in nine sentences, two hundred deceptively plain words full of restrained music and brisk details that a lesser writer would have lingered over. It is all so beguiling that you can easily overlook the paragraph’s strange close: “I got to know the people well, though I never spoke to them and they never spoke to me. I got to know their clothes and style and voices.”

Here, in miniature, is the mysterious flaw at the heart of Naipaul’s genius, the baffling disconnect between his Cadillac prose and the reclusive, almost solipsistic mind that steers it. Why won’t he speak to them? How can a writer who avoids conversation reproduce it so perfectly? Where does this fastidious, detached, and skeptical observer find his incandescent descriptions? The passage ends with a teasing hint: “All my life I have had to think about ways of looking and how they alter the configuration of the world.” We are then led down a long via negativa, in which the right way of seeing must be inferred from others’ mistakes.

Exhibit A: West Indian writers in general, Walcott in particular. In 1949, the sixth formers at Queen’s Royal College learn of a “serious young poet in one of the smaller islands to the north who had just published a marvellous book of poems.” Six years will pass before Naipaul gets round to reading 25 Poems, so he softens us up with disclaimers. As a schoolboy, he tells us, Palgrave’s Golden Treasury “made me think of poetry as something far away, an affectation, a searching for rare emotion and high language.” Oxford, regrettably, doesn’t take him much beyond Marlowe and Shakespeare, so by the time he has reached the BBC, his “judgement in poetry was good enough for most of what came to Caribbean Voices, but it was still crude. I still didn’t go to poetry out of choice . . .”

Then he reads Walcott, and is “overwhelmed” — not so much that he cannot harbour doubts about the long poems being “prosy and difficult,” but enough to see beauty and mystery in “The fishermen rowing homeward in the dusk are not aware of the stillness through which they move,” and the bookish humour in the line “Inspire modesty by means of nightly verses” — “where the modesty could be sexual or poetic.” He learns a few poems by heart, and recites one to David Piper, the director of the National Portrait Gallery:

He, handsome and grave behind his desk, listened carefully and at the end said, “Dylan Thomas.” I knew almost nothing about contemporary poetry, and felt rebuffed and provincial. It was a let-down: perhaps, after all, I didn’t truly understand.

Naipaul does not say so, but the death-of-a-thousand cuts that he then tries to inflict on Walcott seems to be inspired by this moment. Revealingly, although his judgement has been “good enough” for West Indian BBC listeners, he knows “almost nothing about contemporary poetry” when speaking to an educated Englishman. The ignorance is unbearable. If a fondness for Walcott means being provincial, then something better must be found. For Walcott has committed a cardinal sin by sounding like someone else. Naipaul’s obsession with being original and self-created, his ambition to leap fully formed into the world of “litritcher and poultry” which his characters can barely understand, cannot be served by Walcott’s gift.

So we learn — via another Englishman — that Walcott chooses words he hasn’t yet earned the right to, that behind the early work there is a disabling “black” theme, and that “the idea of island beauty, which now seems so natural and correct, was in fact imposed from outside, by things like postage stamps and travel posters . . .”

Before the trap closes, we are offered a context:

The competing empires of Europe had beaten fiercely on these islands, repeopled after the aborigines had gone, turned to sugar islands, places of the lash, where fortunes could be made, sugar the new gold. And at the end, after slavery and sugar, Europe had left behind nothing that could be called a civilisation, no great architecture, no idea of local beauty, no memory of style and splendour . . . And when in the 1940s middle-class people with no home but the islands began to understand the emptiness they were inheriting (before black people claimed it all) they longed for a local culture, something of their very own, to give them a place in the world.

Then we get this:

Walcott in 1949 more than met their need. He sang the praises of the emptiness; he gave it a kind of intellectual substance. He gave their unhappiness a racial twist which made it more manageable.

Ten years later, when he has exhausted “the first flush of his talent” and become “ordinary, a man in need of a job,” Walcott finds himself trapped at the Trinidad Guardian — like Naipaul’s father Seepersad. But he won’t become Biswas:

From this situation he was rescued by the American universities; and his reputation there, paradoxically, then and later, was not that of a man whose talent had been all but strangled by his colonial setting. He became the man who had stayed behind and found beauty in the emptiness from which other writers had fled: a kind of model, in the eyes of people far away.

Much less space is given over to carving up Samuel Selvon, who “burnt up his simple material” early, and Edgar Mittelholzer with his depthless “plantation novels.” George Lamming escapes direct censure, and Seepersad Naipaul is let off lightly. But the great man’s verdict is quite clear: West Indians lack the wintry mind you need in a postcolonial world; they cannot look out at the darkness and behold (in Wallace Stevens’s words) “nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.”

•

Anthony Powell’s literary vision suffers from a different defect: “no narrative skill, perhaps even no thought for narrative.” Writing within a developed, “over-written” society, he lacks the artistry of Evelyn Waugh, who can do both a “wicked fairy tale (Decline and Fall) and later a romance (Brideshead Revisited).” Reading through the major works shortly after Powell’s death, Naipaul is horrified. The plotting is predictable, the form unwieldy, the dialogue ponderous — even though “Powell is a master of the different ways of English speech.” Again, the hatchet is lifted more in sorrow than in anger. Powell was a close friend, he showed Naipaul how to navigate literary London, he was charming and generous. When colleagues and former friends put him down — one of them calls him “the apotheosis of mediocrity” — it feels like betrayal. Auberon Waugh’s infamous review of Powell’s work is “horribly unfair,” but we later discover that Auberon’s father Evelyn “had no time for Tony as a writer, hardly thought of him as a writer, never ran him down but equally never spoke approvingly of him.” Naipaul confesses that he is not sure how true this was, but you can’t help noticing how conveniently the judgement would buttress his own.

The chapters on Gandhi and Flaubert are this book’s saving graces. Pruned of condescension, the analysis of what goes wrong between Madame Bovary and Salammbô is a masterpiece of practical criticism. It is also the closest Naipaul gets to answering his implied questions about ways of looking at the world. Before considering these, however, it is worth recalling some of what he has already said about his own style.

In “Prologue to an Autobiography”, Naipaul remembers the sentence that made him feel like a writer. Hunched over a typewriter in the Victorian-Edwardian gloom of the old Langham hotel where the BBC freelances worked, he came up with this:

Every morning when he got up Hat would sit on the banister of his back verandah and shout across, “What happening there, Bogart?”

It made him want to go on:

Luck was with me, because that first sentence was so direct, so uncluttered, so without complications, that it provoked the sentence that was to follow. Bogart would turn in his bed and mumble softly, so that no one heard, “What happening there, Hat?”

The first sentence was true. The second was invention. But together . . . they had done something extraordinary. Though they had left out everything — the setting, the historical time, the racial and social complexities of the people concerned — they had suggested it all . . .

These tentative beginnings become the opening sentences of Miguel Street, which — although published third — was the first book Naipaul completed. In a real sense, they are the fons et origo for all that comes afterwards, and they prefigure Naipaul’s subsequent work in several intriguing ways. They seamlessly weave together fact and fiction, they contain a musical near-repetition, they finesse the background (nicknames, a back verandah), and they engage their creator because they are lightfooted and cinematic (uncluttered and direct).

That is the Naipaul style: direct and uncluttered. At his best, he disappears completely from the work and the words seem to come alive unaided. Though they could not be further apart in their visions of the world, Philip Roth and Naipaul share a genius for distillation. They both move through material faster than their contemporaries and yet, somehow, magically, you feel they have noticed everything. Naipaul has said many times that he works by intuition alone, without theory or politics to guide him. This sounds entirely plausible for his fiction, but surely it is naïve as an account of his travel writing. Not only are his journeys peopled with characters that could have stepped straight out of the novels — which in a sense they probably have — but the half-formed worlds he so often discovers feel too convenient to be entirely true. Naipaul tends to ridicule expert critics by protesting his simplicity in the face of the Wise Men from the universities, especially those who think he invents episodes or embellishes them. But not all their objections can be set aside so easily.

Reviewing Among the Believers for the New Statesman in 1981, Edward Said called Naipaul a “demystifier of the West crying over the spilt milk of colonialism. The writer of travel journalism — unencumbered with much knowledge or information, and not much interested in imparting any . . . What he sees he sees because it happens before him and, more important, because it confirms what, except for an occasional eye-catching detail, he already knows.” Two of Said’s other observations are worth quoting in full. First:

Seeing oneself free of illusion is a gain in historical awareness, but it also means emptying out one’s historical identity. [Naipaul’s] next step is to proceed through life with a minimum number of attachments: do not overload the mind. Keep it away from history and causes; feel and wait. Record what you see accordingly, and cultivate moral passions.

The trouble here is that a mind-free body gave birth to a superego of astonishingly assertive attitudes . . .

And, even more pointedly:

If it is criticism that the West stands for, good — we want Naipaul to criticise those mad mullahs, vacant Islamic students, and cliché-ridden revolutionaries. But does he write for and to them? Does he live among them, risk their direct retaliation, write in their presence so to speak, and does he like Socrates live through the consequences of his criticism? Not at all. No dialogue. He snipes at them from the Atlantic Monthly where none of them can ever get back at him.

It’s his grandmother’s verandah all over again, but Naipaul isn’t sketching Woodbrook any more, he’s offering the geopolitical centre an account of its vast periphery: hundreds of millions of lives, whole countries and cultures. The novelist’s clutter is their history; remove that and you will still see what is in plain view, but surely a writer of Naipaul’s stature should be able to see more.

•

Gandhi is a case in point. Naipaul illuminates him brilliantly at the personal level: the insecure and highly principled student in London, not simply rushing to finish his exams but “reading through the common law of England in nine hard months,” the polite contrarian asking for curry powder to season his jail food in South Africa. We see a man moulding himself out of whatever is to hand: abandoning breakfast after reading in the paper about “the formation of a No Breakfast Association in Manchester,” forming a commune according to Tolstoy, “disguising his wound . . . [so that] his many causes made him appear more universal than he was.” The self-presentation is tweaked and re-tweaked until Gandhi catches the Zeitgeist.

The Mahatma can be seen comically as a reductio ad absurdum of his experiments (professional lawyer turned latrine-cleaning celibate, labour activist reinvented as dhoti-clad sage and fanatic vegetarian). Naipaul lets us see him this way, as though he is merely an actor, but we also see how easily the roles might have failed to take. The novelist lets us watch the earnest, intuitive way that Gandhi sought for an idea of India that would cede him political control. Far from being a mere trickster, Gandhi becomes an author of himself, the creator of his own myth. It is a very Naipaulian story, and he tells it perfectly.

But what about India at large, the faceless millions that Gandhi will lead? They are there in the background, at the margins of the National Congress in 1925, indecipherable to the visiting Aldous Huxley, intruding into Nehru’s patrician consciousness. Naipaul chooses to leave them there for the sake of an unencumbered story, but then he uses Gandhi’s life, and his own, to suggest far-reaching ideas about the “place of destitution” that lies behind India’s myths. When, for instance, Naipaul’s mother visits her ancestral village, the local women overwhelm her with their good intentions. Because she is too nervous to risk Indian food, Mrs Naipaul agrees to accept a cup of tea.

The tea at length appeared, a murky dark colour, in a small white china cup. The lady offering the cup, for the greater courtesy and the better show, wiped the side of the cup with the palm of her hand. And then someone from these relations of a hundred years before remembered that sugar had to be offered with tea. My mother said it didn’t matter. But the grey grains of sugar came on somebody’s palm and were slid into the tea. And that person, courteous to the end, began to stir the sugar with her finger.

This is superbly reconstructed — from an uncompleted diary entry — but surely Naipaul is indulging in some authorial sleight-of-hand. Would Mrs Naipaul have teased out the implicit comedy so well? The “relations of a hundred years before” are Mrs Naipaul’s contemporaries, but the phrasing makes them, with their murky tea and filthy hands, sound more like the undead. They feel too perfectly half-made not to be Naipaul’s projections. Mrs Naipaul, we are told, ends her account of the incident “in mid-sentence, unable to face that sugar-stirring finger in the cup of tea. The land of myth, of a perfection that at one time had seemed vanished and unreachable, had robbed her of words.” Her son will not be so easily silenced. He will stare down that cup of tea, unblinkingly record the dirty palms and stirring finger, and he will send up this rural backwardness in fearless comic prose.

•

Flaubert is the grandmaster of uncluttered prose, and Naipaul’s analysis of his technique is fascinating. Reconsidering Madame Bovary years after a first reading, he marvels at its density.

I opened the book near the beginning. And there, in five paragraphs at the end of the first chapter, Charles with the help or superintendence of his mother was marrying his first wife: thin, bony, forty-five, a bailiff’s widow from Dieppe, in demand because she is thought to have money . . . All this in five paragraphs: so much that Flaubert would have enjoyed creating, and so much that I had forgotten.

We are then taken on a thrilling tour of the details Flaubert uses to pull readers into his fictional world. Naipaul is brilliantly assured on this material, and his insights on Flaubert are compelling. He uses précis to pick out cinematic details like the farm boy who runs across the snow in wooden shoes and dives through a hedge to open a gate for Charles Bovary. Naipaul admires the way these “swift details” do their work, all the while suggesting everything that goes unmentioned. Many critics have traced Naipaul’s influences back to writers like Somerset Maugham and Aldous Huxley, but his mature tastes seem to tend towards the French. Last year, in a rare moment of praise, he told an interviewer that Maupassant was “a very great man.” Rereading his collected stories “was an education. In the beginning he writes very carefully, not wishing to put a foot wrong. In the middle he is more secure. He does things instinctively and well, and then, near the end of his life, his thoughts are about death, and the pieces get shorter and they are very, very affecting.”

Flaubert, in his Bovary years, is like Maupassant in the middle stage, but instead of achieving greater simplicity with age, Flaubert succumbs to the overheated romanticism of Salammbô. To examine this failure, Naipaul looks at the main source for the later story, a brief account by the Greek historian Polybius of the mercenary war that followed Carthage’s subjugation to Rome. Anxious to prove that he has done lots of research, Flaubert keeps elbowing us with his knowledge, pointing out too many things, always straining after verisimilitude. Polybius is spare and suggestive, Flaubert overstated and laborious. This has the paradoxical effect of making Salammbô indistinct.

[She] slinks about her jeweled temple interior, never less than beautifully described, but since she has little to say it is hard to know what she feels or does or how she actually passes her days. She is a creature of bad nineteenth-century fiction, gothic, orientalist, a lay figure, meant to be seen from a distance. If she were to say too much there would be no illusion.

There is then an absorbing discussion of how writers like Lucretius, Cicero, and Caesar perceived their world. Naipaul is especially good at noticing what they omit, details that contemporaries would have needed no explanations for, like the gruesome practices of war and gladiatorial combat, and the routine abuse of slaves. Then he looks at a poetic idyll called “Moretum”, which is classified with Virgil’s work, but “has sixty-nine non-Virgilian words, and is too realistic to be by Virgil.” The poem describes, in extraordinary detail, the daily life of a smallholder named Simylus. Naipaul luxuriates over the texture of the poem, and he seems particularly engaged by the appearance of Scybale, a black slave who is summoned by Simylus. (We later learn that her name is Greek for dung or rubbish. Naipaul then comments: “So the poor African woman slave was named for what she was thought to work in; she became ‘Miss Manure’: horrible, this insult lodged in a beautiful idyll.”)

She is a black African — the only black African I know in Latin literature — and, perhaps because she is unusual, she (unlike Simylus) is described in detail: curly hair, swollen lips, dark (fusca colore), broad-chested, her breasts hanging low, her belly flat, her legs thin, her feet broad and flat. Her shoes are torn in many places.

Naipaul loves this sort of writing because it takes “nothing for granted, making us see and touch and feel at every point, celebrat[ing] the physical world in an almost religious way.” This way of seeing dies out almost completely, killed by Roman rhetoric, until Tolstoy reads Greek in mid-life and writes the old sorts of stories. It is the closest Naipaul comes to providing a direct answer to the riddle of the world, and it is one that is bound to exercise his critics even further.

•

In the memoir of his friendship with Naipaul, Paul Theroux records a vignette that nicely captures the problem of deciding what Naipaul sees when he looks out at the world. The story begins at a party in New York, where a man sees the Indian writer Ved Mehta holding forth to a small circle of admirers. Mehta’s books are filled with precise visual details, and the man doubts that a completely blind person — as Mehta is said to be — can write like that. So he goes over to where Mehta is sitting and began to make faces at him. This yields nothing, so the man waves his hands in front of Mehta’s face, he wags his fingers and sticks his tongue out — all to no avail. Throughout these trials, the writer carries on speaking without giving any hint that he knows someone else is nearby. Now the man feels uncomfortable and he decides to go home. As he is leaving, he explains himself to the hostess: “I had always thought Ved Mehta was faking his blindness, or at least exaggerating. [But] I am now convinced that Ved Mehta is blind.”

“That’s not Ved Mehta,” said the hostess, “it’s V.S. Naipaul.”

If true, the incident may be evidence of Naipaul’s perfect manners towards a boor, but it can also be read as an instance of extreme self-absorption, a glimpse at a man so caught up in his own sententiae that he will not acknowledge an elephant in the room. If you incline towards the first interpretation, A Writer’s People will seem like the uneven work of an aging master; if, however, you prefer the second, you will probably reach very different conclusions.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, February 2008

Brendan de Caires was born in Guyana and now lives in Toronto. He has worked as an editor for various publishers, and written book reviews for Caribbean Beat, Kyk-Over-Al, and the Stabroek News.