Final return

By Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw and J. Michael Dash

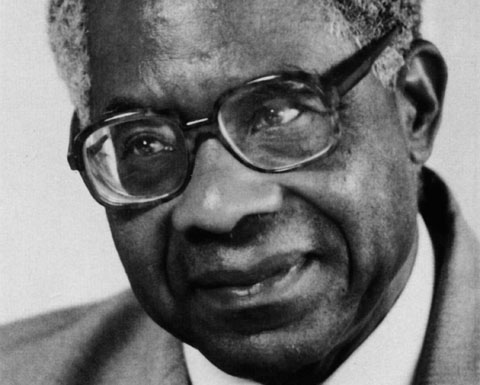

Aimé Césaire, 1913–2008

What seemed to be surrender was redemption. What seemed the loss of tradition was its renewal. What seemed the death of faith was its rebirth.

— Derek Walcott

In the Caribbean, language more than geography separates us. A great poet in one region may be a mere shadow in another. Aimé Césaire, one of the greatest poets of the Caribbean, passed away on April 17, 2008, in Martinique, his home. “Martinique pleure” (“Martinique is crying”) was one of the newspaper headlines in the French-speaking island, but in the English-speaking Caribbean territories little was reported on Césaire’s death; such silence could only suggest that this poet, playwright, and politician was in fact a shadow to many Anglophone readers. A writer’s death is a mixed blessing; we mourn the loss but the loss makes us return to what we mourn.

Césaire was born in the town of Basse-Pointe in 1913. An exceptional student, he received a scholarship in 1931 and went on to attend some of the most prestigious schools in Paris. It was during this time that he met Léopold Sédar Senghor, the Senegalese writer and statesmen, and Léon Damas from French Guiana. These three young French-speaking scholars became the founding members of the Négritude movement. They united in their desire to redefine the black experience through a rejection of Western ideology that inherently saw blacks as inferior. They were inspired by the zeitgeist; Paris had become the intellectual setting for members of the Harlem Renaissance, writers like Langston Hughes and Richard Wright, who had left the United States to escape racism and segregation. Négritude was conceived of as universal, to include all people of African descent and of the African diaspora.

Césaire’s Négritude was expressed in his poetics and his politics; his legacy is located in both these arenas. With a political career in Martinique that spanned decades, Césaire was not without his critics. Yet Martinican politics always had a voice, from the moment Césaire became mayor of Fort-de-France in 1945 to his retirement in 2001.

In Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (Notebook of a Return to the Native Land), written in 1939, Césaire explored his Négritude through the tropes of revolution and return. If the content of the poem explored and transgressed the Homeric trials of a return voyage, the real revolution would take place in the poem’s form. This long poem is one of his greatest gifts to the Caribbean and to literature. The Cahier explodes like a volcanic eruption on the page, its lava flowing over all that came before. The poem takes a surrealist plunge into the unknown, but in so doing the poet creates and names a new landscape in a voice that was never heard before.

In later years, Césaire’s Négritude was criticised for its inability to ultimately define the complex, diverse, heterogeneous nature of the Caribbean experience. Although Martinican writers and theorists like Édouard Glissant and members of the Créolité movement — Patrick Chamoiseau, Raphaël Confiant, and Jean Bernabé — articulated Négritude’s limitations, they acknowledged Césaire’s role in their vision of Caribbeanness, making them “forever Césaire’s sons.”

Great poetry surpasses politics with its own truth, to move beyond ideological debate; this perhaps is Césaire’s greatest lesson to us.

Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw

•

One of the most widely accepted truths of Francophone Caribbean literature — and, for some, perhaps Caribbean literature as a whole — is that no poetry existed before 1939. The reasons for this belief are obvious. Before the publication of Aimé Césaire’s Cahier d’un retour au pays natal on the eve of the Second World War, there was every reason to believe that Caribbean poetry, or at least French West Indian poetry, was dominated by sentimental, pastoral, and most importantly apolitical doggerel. As Frantz Fanon put it in 1955, “Until 1939 the West Indian lived, thought, dreamed, composed poems, wrote novels exactly as a white man would have done.” In 1939, a new idea of modern poetry was introduced to the Caribbean in Césaire’s modestly titled, epic poem.

Fanon’s sweeping claim may have been a gross exaggeration, since he paid no attention to the militant poetry written in occupied Haiti, but he was on to something as far as a Césairean poetics was concerned. It would be more accurate to say that there was no Césairean poetry before 1939. Césaire’s visionary verse inaugurated a new way of writing and of envisioning new beginnings. In the face of a “sterile and mute land,” as he put it in his introduction to the journal Tropiques, poetry was the howl of protest, a summons to rouse the slumbering, seismic forces silenced by colonial repression. The kind of homecoming envisaged in Césaire’s poem is less physical than poetic. It is about releasing the power of metaphor or re-establishing the bond between word and world. In writing back to the inauthentic, counterfeit verse of the past, Césaire sought a language that can genuinely represent all that was previously thought unworthy of poetry.

Perhaps Césaire’s gift to the global movement of decolonisation in the decades to follow was the ideology of Négritude. In any case, others, such as his fellow poet Léopold Sédar Senghor, had much more to say about the concept than he did. Also he was never tempted, as others disastrously were, to turn Négritude into official state policy. His impact on the Caribbean is tied rather to the allegory of a triumphant poetic and psychic homecoming. In 1939, a heroic modernism tempted Césaire to conceive of the Francophone Caribbean in terms of violent images of revolutionary decolonisation, but also in terms of an unprecedented attentiveness to Caribbean space. The Caribbean past was represented as a sea of running sores, a bloody, open wound with its archipelago of precarious scabs. The poet proposed a volcanic reordering of space, where the tongue of volcanic flame would sweep away the old and found a new utopian order.

The very last word of the Notebook, verrition, and arguably its most important, is a Césairean neologism meaning a “sweeping away.” Writing in Tropiques in 1941, in accordance with the dictates of a poetics of sweeping away the past, Césaire declared that all he saw around him in the Caribbean during the war years was a world of monstrous silence and encroaching shadows. This was a time of great material privation, as France’s Caribbean colonies were isolated by an Allied blockade. It was also a time of great literary activism and a concerted attempt to rethink Négritude and Surrealist ideas, in particular in terms of a Caribbean unconscious. The 1940s were a time of Caribbean homecomings. This was true for the Cuban painter Wifredo Lam, whose painting The Jungle, done on his return to the Caribbean, can be seen as the pictorial equivalent of Césaire’s landmark poem. It is also true of Haiti’s Jacques Roumain, whose return from exile led to the novel Masters of the Dew, which is about reconciling language and landscape. Today, Césaire’s ideology, which harks back to a specific period of anti-colonial politics, may seem dated. However, Césaire’s poetics, forged in the chaotic aftermath of what he saw as the catastrophic shipwreck of Caribbean history, is still very much part of what we call modern Caribbean literature.

J. Michael Dash

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, May 2008

Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw is a lecturer in French literature at the University of the West Indies, St Augustine. Her first book of short fiction, Four Taxis Facing North, was published in 2007.

J. Michael Dash, a Trinidadian, is professor of French at New York University. He has written on Haiti and Edouard Glissant. His most recent book is Culture and Customs of Haiti (2001).