Life studies

By Melanie Archer

Golden Glance, by Rachel Amy Rochford

In2Art, St Ann’s, Trinidad; 16 to 26 April, 2008

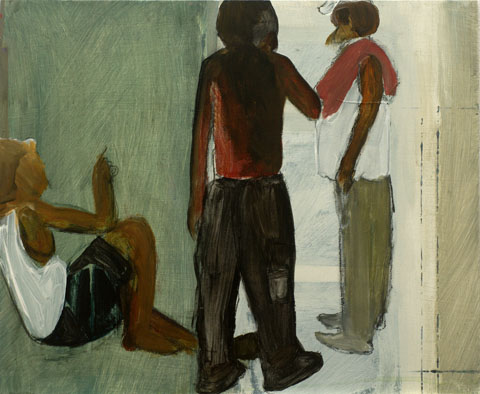

Making a Point (2008), 14 x 17 inches, acrylic on board

Here’s a fun little exercise: read the following words while thinking of the last few pieces of “Caribbean” art you saw:

. . . Often [artists] believe they can work instinctively and aimlessly, like Nature, which, without visible purpose, gives form and colour to crystals, plants, stones — everything that exists. They give their paintings obscure names, or just numbers. Evidently this method is based upon the attempt to produce pure stimulus, as in music, through intentional elimination of all other effectual possibilities. The painter is to be nothing but a creator of form and colour. Whether these artists believe their work has no “deeper meaning,” or whether they impart to it an emotional or metaphysical meaning hardly perceptible to the spectator, the fact remains that they intentionally renounce all the artist’s possibilities of ideological influence (in areas of eroticism, religion, politics, aesthetics, morality, etc.), standing silent and indifferent, that is, irresponsibly, in relation to social occurrence, or — in cases where that is not the intention — they work in vain through ignorance and ineptitude.

— From Wanderers Into the Void, published as part of the 1925 essay “Art Is in Danger”, by George Grosz (1893–1959)

and Wieland Herzfelde (1896–1988)

Although written for a much different time and place, the ideas expressed by Grosz and Herzfelde find a struggle-free fit in Trinidad and Tobago’s contemporary art world (and, possibly, that of most of the English-speaking Caribbean as well). Should they seem a little harsh, cast your mind back to the majority of the exhibitions you’ve attended, and the disheartening feeling that you and your sleepy, unstimulated eye had stood in that space before. This syndrome depresses, while making the truly invested viewer wonder if artists, not to mention gallery owners, are pandering to wealthy entrepreneurs and tourists who find paint easier to live with than ideas and questions. Even the whispered promise of a new gallery brings the nascent dread of having to look upon yet another laughably pretentiously blob of paint or colourful photograph depicting coconut trees, coconut trees, seascape, coconut trees.

While the Lite Art syndrome is as commonplace in Trinidad as, well, coconut trees, every now and then a body of work appears that charms the viewer and breaks the dull spell. Rachel Amy Rochford’s eighth solo exhibition, Golden Glance, was one such show. Born in 1978, Rochford graduated with a BA in art from the University of Reading in 2005. While her career has extended beyond painting to lecturing and photography and film work for the Carnival Institute of Trinidad and Tobago, the majority of her time is devoted to her studio practice — alongside her local solo shows, she has taken part in numerous group exhibitions in Trinidad, Britain, and France.

Of the fifty-two paintings in Golden Glance, roughly half are a direct continuation of Rochford’s exploration of “the artistic evolution of traditional African masks and sculptures in their depiction of human expression.” The masks, which have actively interested her in recent years, play with line and colour and form, and appear well researched: evident in their sinuous forms and shapes are various cultural influences — Asian, North American Indian, Mexican, Amerindian. While technically sound and quite beautiful, the mask paintings in Golden Glance fall short in offering up much in the way of a relevant social statement, or the newness I groused about in the preceding lines. The viewing public seemed to agree — a survey of the exhibition revealed the majority of red “sold” dots spattered other groups of paintings (oh, admit it, you check the dots too), while a nosy peek into the guestbook revealed one person’s insight that Rochford is at her best when she’s here — not in Africa or Europe, but casting an introspective glance on the attitudes and habits of fellow Trinidadians.

Talking Point 1 (2008), 16 x 16 inches, acrylic on canvas

Talking Point 2 (2008), 16 x 16 inches, acrylic on canvas

Three series in Golden Glance succeed in casting just such a glance, overriding any banality found in the other works, and quickly rendering the show a success on the whole. Talking Point is a series of four paintings (all painted in 2008, 16 x 16 inches, acrylic on canvas), snippets of moments captured in Trinidad, each work dominated by green, orange, yellow, or blue. Rochford enjoys driving around with her camera, taking snapshots out of the window. “I love catching people unaware — you know, those spontaneous moments of life at the edge of the road,” she explains. Talking Point 1 depicts three shadowy figures engaged in conversation in front of a roadside vendor. The background is flat and orange, the figures flat and black, but under those two colours a myriad rich, warm hues lurk, adding impossible depth to the flatness. The vendor’s tabletop acts as a horizon, cutting the figures off just below the waist. The painting demands to be read as abstract, thanks to a lack of figural detail and the broad band of black that divides the canvas. Taken from rural central Trinidad — “hence the ‘goat’” Rochford states, chuckling — the scene is a standout example of her sophisticated depictions of the most ordinary activities of daily life. Some people gathered for some goat have never seemed as charming, or worthy of attention, as they do here. The other atmospheric, pared-down landscapes in the Talking Point series similarly place random moments in abeyance for the viewer’s consideration. In Talking Point 2, bands and slivers of black against a brilliant yellow background again roughly divide the canvas, this time suggesting the presence of the road of which Rochford speaks. Three cutout figures dominate once more, and while the reason (if any) for their gathering is left unstated, the painting has an air of reverie.

While not immediately evident as a series, a separate group of five paintings draws heavily on frozen moments and landscapes, this time with subtle palettes and slightly more detailed figures. Brothers (2008, 20 x 16 inches, acrylic on board) shows two men who Rochford later reveals are “brothers” not by genetics, but through the camaraderie they share as construction workers. That closeness is echoed, uncomfortably, in the composition of the piece — although seemingly passive and at repose, the pair struggle for equal space within the frame. Perhaps on a lunch break, perhaps huddled over some task, their backs are to the viewer, heads close together and bodies aligned on the same diagonal. Whether meaning to or not, Rochford creates tension with this pair — careful regard of the piece promotes musings of the larger turf wars “brothers” face.

Of similar style and palette, Making a Point shows three men, two standing and one seated on the ground, engaged in a debate. Bands of colour divide the piece, this time vertically: greens and warm, earthy tints dominate. With his back resting on a wall suggested by the left edge of the piece, the seated man points directly at the man standing in front of him, t-shirt flung just so over his shoulder, as if to say, “Man, yuh not listening.” Here, the flesh-coloured tones of limbs link the figures, their highly stylised rendering forming abstracted shapes.

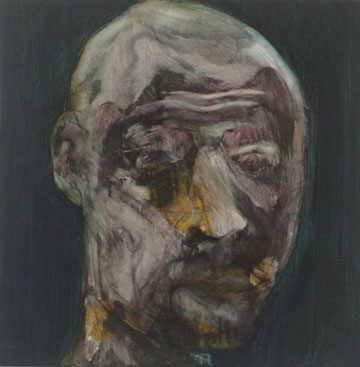

I’m Just As Disturbed About It As You, Man (2008), 16 x 16 inches, acrylic on canvas

Think It Over, Man (2008), 16 x 16 inches, acrylic on canvas

Inching closer to self-examination and ever-present musings of what it means to be Trinbagonian is Rochford’s standout series of seven headshots — especially commendable, as they mark the first time the artist has painted the human face in detail. Rich, warm tones and an economy of motion define each canvas. This series (known, in my mind, as the “Talking Heads”) finds its genesis in the artist’s mask explorations, but takes a closer look “particularly at attitudes among Trinbagonians.” Here, common sentiments are “etched onto . . . faces. It is through the stance of a man, in a series of friezes, that [Rochford] depicts the essence of our human landscape. It is the idea of being able to recognise ourselves, at a glance at forty paces; walking, sitting, talking.” Although executed with a tighter hand (and focused on the other sex), these heads evoke the portrait work of the South African artist Marlene Dumas (born in 1953), who for years has tirelessly probed notions of identity and self-image through an endless series of up-close, in-your-face(s) paintings of varied individuals. Like Dumas, Rochford doesn’t paint these portraits from life, but from the local media — these multiracial heads were culled from photographs that appeared in the daily newspapers. Facial expression or comportment define how the artist then named them — a tongue-in-cheek system that cleverly ends each title with the word “man,” and places each in conversation with the viewer. That clever little word assigns a specific attribute to the character in question (It Could Never Happen to Me, Man), acknowledges an unnamed issue (I’m Just As Disturbed About It As You, Man), asks a question (Where Do We Go From Here, Man?), or provides an edict by which we can be guided (Never Look Back, Man). While each head fills the frame and looms larger than life, they are not confrontational, nor do they have the eeriness of Dumas’s portraits. Rather, the loose strokes abstract the men, blurring their identity just enough that viewers can neatly place themselves onto the canvas.

It is a generally accepted truth that life is what happens when you’re waiting for life to happen. Rochford’s work echoes this sentiment — particularly her interest in goings-on at the edge of the road. Answers can be found there — an apt metaphor for not just a daily existence, but also for the artist’s method of working in her studio, where she paints every day for roughly nine hours, keeping her hands busy rather than waiting for some vague, over-relied-upon “inspiration” to hit. Asked what’s next, Rochford pauses, thinks, and then says, “Good question . . . paint more heads, I think. I’ve only done seven.”

Introspection is difficult, particularly because we can never really see ourselves as others see us. Yet with this new body of work, through the unlikely avenue of leaning more towards abstraction and ideas, Rochford has brought both her painting and herself into sharper focus. It seems that, for the artist, the act of studying others has led not just to identifying the individuals in question, but understanding a little of herself as well. We should all be so lucky.

Golden Glance (2008), 16 x 12 inches, acrylic on canvas

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, May 2008

Melanie Archer is former managing editor of DAP/Distributed Art Publishers in New York. Now based in Trinidad, she is co-authoring a book on the representation of girlhood in contemporary art.