Less is more

By Melanie Archer

Meiling: Fashion Designer, by Judy Raymond

Robert and Christopher Publishers, ISBN 9789768211347, 144 pp

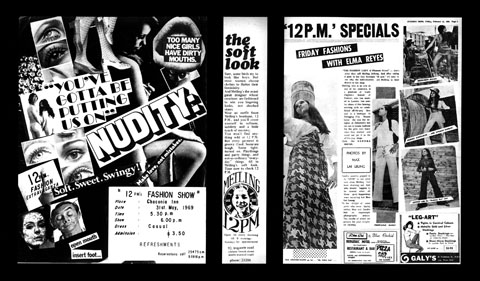

Press clippings (c. 1969) from the Meiling archive. Images courtesy Robert and Christopher Publishers

I don’t believe in fashion, I believe in style. There’s trendy and there’s stylish. A woman always has to find what suits her. But she mustn’t be stuck in a time warp, and she shouldn’t be a fashion victim. That’s a very expensive exercise.

— Meiling

Wisdom states we should never judge a book by its cover. People in the illustrated publishing business state otherwise. Much like a person’s outfit, a book’s cover can quickly grab our attention, increasing (or, in unfortunate cases, diminishing) our interest in taking a less superficial look. With books, our second attention-grabbing visual is a casual flip through the pages; design plays an important role.

When I first picked up Meiling: Fashion Designer I thought it would be something, well . . . more. Here is a book on a woman who is, arguably, Trinidad and Tobago’s most talented and prolific designer. Some visual reflection of this in the book’s pages seemed in order — perhaps, as an object, it would reflect one of her pieces; meticulously assembled, stylish, and with an unexpected flourish that sets it apart from other books. Or maybe there was some way to vamp on the fact that the designer is perennially, stylishly clad in black, with the occasional red or some such accent. The book’s cover attempts, perhaps, to smartly reflect this — a black dust jacket with “Meiling” repeated in a clear varnish, the text only visible when the light catches it. But then there is one instance of the title printed in white, which kills the black-on-black effect (successfully executed on the hard binding itself). As I spent a little time with Meiling, though, I started wondering if the book/cover/judgment issue was even relevant. As I spent more and more time with it, I realised I might have missed the point entirely.

Meiling herself states, “I like clean, simple, minimal. My thing is ‘Less is more.’” On the other hand, she also notes, “I love romantic looks, though I’m not a girly person: bows, satin, frills . . .” A look through the book confirms this: on one page, a beige crushed cotton smock — simple, elegant. Turn the page: a top constructed of layers of petal-shaped, light, beaded, rose-coloured fabric, with a skirt of varying textures. It became clear that my initial expectation was unrealistic: a book remains constant through its print run, whereas Meiling does not produce more than one of the same garment. And (to state the obvious) unlike a woman prone to mood dressing, a book is a static object, fixed in structure and content; therefore it is impossible to hope that its visuals could faithfully reflect Meiling’s oeuvre. Instead of some superficial take on a body of work, shouldn’t a fashion designer’s monograph aim to faithfully illustrate her methodology and focus through her lines, a strong sense of style acting as the thread that unifies pieces through the decades? Additionally, wouldn’t it be insightful to present a bit of the designer’s background and how her clothes fit into the greater social context? Yes and yes — Meiling hits these targets with ease.

However, if you’re merely looking for a quick summary of the designer’s career, you won’t find it here. Biographical tidbits and juicy morsels of info — such as the answer to the mystery of why the designer always wears black (no, I’m not telling) — are sprinkled throughout fifteen “gentle and insightful” chapters written by Judy Raymond. A read through these chapters reveals a painstakingly researched and compiled story that takes us from Meiling’s UK-based schooling through her famously theatrical early shows at the Little Carib Theatre to last year’s photo shoots. Instead of being structured chronologically, they are arranged by theme, with titles such as “Meiling’s Calendar”, “Caribbean Chic”, “Something Old, Something New”, “Making the Mas”, and “La Vie en Noir”. “’I Was a Flower Child’” tells of Meiling’s London days. Younger followers of the designer’s work will delight in possibly never-before-seen images of her pieces from the late 1960s through the early 70s, while older . . . er, more seasoned followers will reminisce on impossibly stylish days gone by. Micro mini shift, anyone? Bell-bottoms with a flair for flare?

•

Fittingly, Meiling opens with the chapter “Let There Be Light”, which recalls Raymond’s visit to Meiling’s studio during pre-show fittings. The author’s descriptions of Meiling’s pieces sparkle, with mini lessons in fashion history seamlessly woven through the narrative. Raymond’s knowledge of, enthusiasm for, and research into her topic shine through the prose, yet in many cases she eschews her own conclusions in favour of a simple recolle tion of Meiling’s words or those of the designer’s longtime collaborators. Among these are musician Wendell Manwarren, jeweller Jasmine Thomas-Girvan, and model Wendy Fitzwilliam. Flies on the wall, we buzz into fitting rooms and through Meiling’s studio, where half-naked Amazons stand, then onto the stage and back again.

In addition to the comprehensive yet obvious photographs from shows and shoots, Meiling charms the reader with a treasure trove of images from the designer’s personal and professional past, as well as numerous behind-the-scene shots and reproductions of ephemera. If you ever wanted to know what Meiling looked like as a baby or during her “freedom” days of the 1960s, get this book. Likewise, if you ever wondered what goes on behind the curtain, what a fitting looks like, what a marked-up contact sheet looks like, what Meiling’s workspace looks like, or have wished to review her various collaborations with masman Peter Minshall. Also reproduced here are several press clips dating from the late 60s, as well as invitations to shows and fittings that also span the decades. Images are laid out on a simple grid; a neat structure is favoured.

There is, however, a bit of a stain down the front of this otherwise pristine piece. On the book’s colophon page, an errata list with stylist and photograph editing credits has been tipped in. It’s an unfortunate oversight: looking through Meiling, it’s clear that someone — more than likely, several people — had a tremendous task laid before them of culling and editing hundreds of archive images from a range of photographers down to the ones that made the final cut.

Thankfully, Meiling is a strong enough publication that we can overlook this to focus on the successes here. It is a well-put-together, insightful, extensive look at a designer that is all of those things. Meiling reminds me of that piece of clothing that you buy because it’s terribly smart. Like the much-touted little black dress, it’s understated yet elegant — a comfortable piece that you will find yourself reaching for time and time again.

Please, dry clean only.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, November 2008

Melanie Archer is a former managing editor of DAP/Distributed Art Publishers in New York. She is now based in Trinidad.