Ways of seeing

By John T. Gilmore

Slavery, Sugar, and the Culture of Refinement: Picturing

the British West Indies, 1700–1840, by Kay Dian Kriz

Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, ISBN 9780300140620, 288 pp

From the early twentieth century onwards, the Caribbean has been home to increasing numbers of accomplished indigenous artists who have sought to analyse the region’s life and culture through visual media, to create forms which in different ways reflect Caribbean identities, or simply to give pleasure to themselves or their viewers. While such artists have undoubtedly been more prevalent in larger and more populous countries such as Cuba and Jamaica, which have provided private and public patronage on a larger scale, smaller countries also have good reason to be proud of their contributions in the visual arts as well as in literature.

The obvious example is St Lucia, which has given the world the painter Dunstan St Omer as well as Derek Walcott. For a good many years now, the work of museum and gallery staff, art historians, and private collectors has documented the achievement of contemporary artists in exhibition catalogues and other published studies, as well as taking the story back to cover artists of the pre-independence period in various countries. This has justly been seen as part of the whole history of the movement towards self-determination in the cultural as well as the political sphere.

But what of earlier times? There have been studies of what one may, for the sake of convenience, refer to as “popular culture” — that is, the culture of the masses who, though excluded for so much of history from wealth and power, have had their own creativity which has contributed so largely to the work of today’s artists in different genres. These studies have examined both aspects of modern Caribbean culture such as Carnival, proverbs, and colloquial speech, and their historical roots. In reaction to the historiography of earlier generations, which saw the history of the Caribbean almost exclusively in terms of the histories of the region’s elites, there has been an understandable emphasis on the histories of the oppressed and the dispossessed. Taken together with the importance placed on written documents, this has perhaps led to a devaluation of the very considerable amount of visual material relating to the Caribbean in earlier periods, which has often been used, if at all, only as picturesque illustrations to document-based histories.

Contributing to this has been the fact that most visual images of the Caribbean before the late nineteenth century were created by artists from outside the region, primarily for extra-regional consumption. Where there were local consumers, these were almost exclusively from elite groups — one thinks of things like the monuments in older Caribbean churches, which are sometimes impressive examples of European sculpture, or the portraits of planters and officials which can be seen in local museums or, occasionally, still found in private collections. These have attracted attention from those interested in elite genealogies, such as V.L. Oliver, whose periodical Caribbeana (published from 1910 to 1919) reproduced a number of such portraits which may now be lost or otherwise unidentifiable (and which remains an under-appreciated resource for historians of the Caribbean with much wider views than those of the original compiler). Or those whose interests lay mainly elsewhere, as suggested by the title of Lesley Lewis’s study “English commemorative sculpture in Jamaica” — while this may have been published in the Jamaican Historical Review in 1972, it had originally appeared in the British periodical Commemorative Art. Generally, however, most modern writers working on Caribbean history and culture did not see such objects as offering anything which required further investigation.

This has begun to change in recent years. Works like David Dabydeen’s Hogarth’s Blacks (1985) or Hugh Honour’s 1989 volumes in the still incomplete series The Image of the Black in Western Art showed how visual images could serve as documents in the history of the African diaspora, and could be read in detail, instead of being merely decorative illustrations in a more traditional history. Marcus Wood’s Blind Memory (2000) is a pioneering analysis of, in the words of its subtitle, “Visual Representations of Slavery in England and America, 1780–1865”, which inevitably includes much that is relevant to Caribbean history. A major recent publication is Art and Emancipation in Jamaica: Isaac Mendes Belisario and his Worlds (2007; reviewed in the February 2008 CRB). After this volume, no one will ever again be able to view Belisario’s well-known images of early nineteenth-century Jamaican Jonkonnu masqueraders as straightforward illustrations of local folklore — they raise many more questions than they answer.

•

Kay Dian Kriz was one of the contributors to Art and Emancipation in Jamaica, and some of her material from that volume is used in Slavery, Sugar, and the Culture of Refinement, but she also explores a number of other areas. The prosperity of the British Caribbean colonies depended on the production of raw sugar which was exported to be refined in Britain, but the colonies were also part of a “culture of refinement” in the sense that the wealth they created produced a demand in Britain for information or propaganda about them which was often presented in visual forms, and also for visual representations which were consumed within the Caribbean by the region’s elites.

Kriz begins by examining the illustrations in Hans Sloane’s Voyage . . . to Jamaica (1707–1725) and showing how these are in some ways at odds with the text. They “refine” the picture of Jamaican society by what they leave out as much as by what they include — there is little directly related to sugar and slavery. Nevertheless, an engraving like the one of coral-encrusted Spanish coins recovered from a shipwreck can be read as validating British rule in Jamaica by confining the island’s previous colonial rulers firmly to the past. Agostino Brunias’s paintings of slaves, free coloured people, and Amerindians in Dominica and St Vincent in the later eighteenth century are interpreted as propaganda for settlement in territories recently acquired by Britain: “the island’s appeal as a potentially civilised space, as well as a profitable one, had to be emphasised” (italics in the original).

A chapter on “caricature and the West Indies on the eve of Abolition” looks at images which have been studied before, or could even be described as widely known, such as Thomas Stothard’s Sable Venus or James Gillray’s Barbarities in the West Indies, but also at some much less familiar material which enables Kriz to carry the discussion beyond the usual issues of anti-slave trade propaganda to a nuanced and wider discussion of what visual images can suggest about the history of racial attitudes in the period. Kriz goes on to explore Belisario’s images as “making a Black Folk” at the end of slavery, and how they might suggest a programme for post-emancipation society — a programme in which the black subjects of Belisario’s prints would continue to be different from, and relegated to a position inferior to, the white elite who constituted the subscribers to and purchasers of the images. As Kriz points out, a feature of many early representations of the Caribbean, such as those by Brunias and Belisario, is the relative absence of white Caribbean people, as artists concentrate on those who are racially different from the assumed white viewer (though this writer wonders if the figure in the white dress in Brunias’s Linen Market, or the mother and daughter in one of Belisario’s Actor-Boy prints, might not be white rather than mixed race as suggested by Kriz — the wearing of a head-tie is not necessarily conclusive).

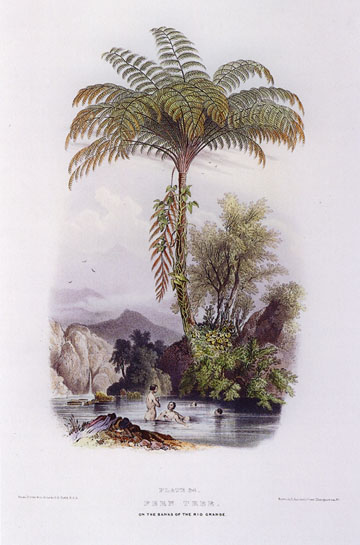

The Fern Tree, from Illustrations of Jamaica (1838–40), by Joseph Bartholomew Kidd; lithograph with watercolour. Image courtesy Yale University Press

In her final chapter, Kriz examines a surprisingly wide range of topographical prints of Jamaica from the early nineteenth century, and shows how these do make space for white figures, in a manner she interprets as reasserting the position of Jamaica’s white creole elite at a time of social and political upheaval caused by the slave rebellion of 1831–2, and emancipation and its aftermath.

The illustrations as a whole are of excellent quality, even if some are perhaps reproduced a little too small for comfort, and the author does discuss some fine details which are difficult or impossible for the reader to see in the reproductions, even with a magnifying glass (e.g. the racial identity of the female figures in plates 90 and 101). One theme which runs through the book is that of how visual representations of the Caribbean in this period are part of the wider history of European art, and the analysis benefits from, for example, seeing the career of the Italian Brunias as a whole, rather than viewing his Caribbean pictures in isolation, or from comparing Belisario’s Sketches of Character with representations of working-class English people. However, there are some respects in which other comparisons might have been useful. For example, while Kriz mentions elite portraiture in passing, more detailed consideration of material like the portraits and monumental sculpture mentioned earlier might have modified the impression of the absence of white figures from images of the Caribbean, which is surely dependent to some extent on genre. It is also the case that the book concentrates on the work of professional artists, though an examination of amateur sketches would also shed light on some of the ways in which the Caribbean was seen. For example, the crude ink and watercolour sketches which the Scottish physician Jonathan Troup included in his diary of his time in Dominica from 1788 to 1790 (now in the Aberdeen University Library) offer representations of the island which are much less “refined” than those of Brunias in a good many ways. The amount of similar amateur material which could be tracked down in libraries and archives in the Caribbean and elsewhere is probably very considerable.

While Kriz’s analysis of individual images is often very detailed, there are a few places where she seems to have missed points of potential interest. She sees Joseph Bartholomew Kidd’s Fern Tree lithograph, from his Illustrations of Jamaica series (1838–1840), with its “Arcadian vision of four nude bathers enjoying a dip in the waters of the Rio Grande,” as appearing “to represent an emergent indigenous ‘race’ of white West Indians whose difference from Britons and Europeans derives from their sustained exposure to the tropical climate,” arguing that “this idea of an emergent white creole ‘race’” is “consistent with the creolisation of the landscape and built environment that marks so many of the views.” She notes that Kidd shows the bathers “in a secluded pool under the shade of a tree that exhibits more signs of death than growth: all but two of its uppermost leaves are turning orange at the tips,” and goes on to discuss “whether or not viewers responded to the cues offered by the dying tree and interpreted these white creole bathers as a ‘dying race’ or as simply happy (white) natives enjoying the pleasures of a beneficent tropical nature.” While she comments on how “a large lower frond has died and is only held in place by a green vine that has grown up the trunk of the tree,” what she does not mention is the fact that it is clearly a specimen of the dodder or love-vine, and that it is the vine which is killing the tree. In early nineteenth-century Jamaica, the love-vine around the tree was referred to as “the Scotchman hugging the Creole” (see quotations in Cassidy and Le Page’s Dictionary of Jamaican English, under “Scotchman”). This takes on a certain irony in view of the fact that Kidd was a Scot — to what extent was he setting out to give the creole elite what they wanted to see, or exploiting them as material which would help to sell his Illustrations of Jamaica in North America and Britain for his own financial benefit, in the same way that other artists had exploited black Caribbean people as subject matter?

Nevertheless, whether or not one agrees with Kriz’s interpretations, they are always stimulating, and by drawing attention to such an extraordinary variety of images, her book performs a valuable function and should encourage further research in this area.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, November 2008

John T. Gilmore is an associate professor at the University of Warwick, where he teaches at the Centre for Caribbean Studies. He is a former managing editor of Caribbean Week.