Guzum power

By Kei Miller

The Book of Night Women, by Marlon James

Riverhead, ISBN 978-1-59448-857-3, 417 pp

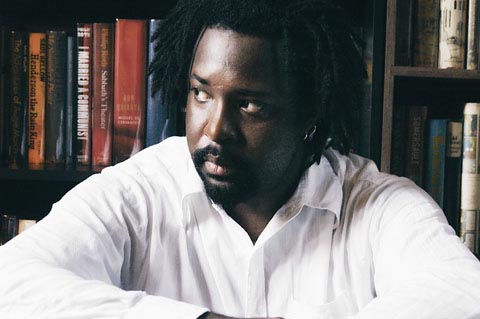

Marlon James. Photo by Simon Levy, courtesy Riverhead Books

If I was to talk de truth and shame de devil, I would tell you I wasn’t happy when Marlon James’s first novel came out. I was finishing my own first novel at the time, on the brink of “emerging,” as it were, and then this fellow who I hadn’t heard of from Adam came out with his own book, John Crow’s Devil. It wasn’t my “thunder” I thought he had stolen; I was under no illusion that Caribbean writers debuted with any sort of bang. Yet it was still jealousy of a kind, and something else — annoyance.

Instead of my thunder, James had stolen my canon: in interviews, he raved about how Salman Rushdie’s Shame had opened his eyes to the possibilities of fiction (it had done the same for me); how Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon had taught him how fiction could soar (it had taught me the same lesson); and how Earl Lovelace’s Wine of Astonishment had frankly astonished him (it had astonished me). He had stolen my biography: Wolmer’s Old Boy; UWI literature student; black boy with dreadlocks from a Jamaican middle-class home who spent years of serious involvement in the church. And, from all the blurbs, it seemed he had stolen my plot: village in Jamaica; fight between good and evil; pastor as the antagonist; big house in the village which becomes the locus of evil, and which everyone marches to in the end.

I went online at the time, found an excerpt from this Johncrow novel, half hoping it would be bad; it wasn’t. Only at James’s book launch in Kingston did I finally get some warped satisfaction: there was far too much self-congratulation from the publisher, who went on and on about how utterly edgy the novel was, and how (snicker, snicker) when read at some embassy or the other (snicker, snicker), all the women had blushed (snicker, snicker). His subsequent pronouncements on the book, even by the standards of a book launch, were far too superlative, and then all the sex and bizarreness in James’s reading felt gratuitous. Alas, even that last bit of critique dissipated when I actually read the novel, and everything felt earned. There was only one last resort. At the launch I leaned over to my best friend and declared, “Well . . . at least I think I’m better-looking.”

God forgive me that moment of false vanity! The back cover of James’s new novel, The Book of Night Women, reveals him at thirty-eight still having a full and magnificent head of hair. I, who have only just begun my thirties, find that my hairline has dramatically receded. I approach James’s new novel, therefore, with the attitude that befits a newly balding man — with maturity, a certain magnanimity — and an appreciation of the power of James’s guzum.

Guzum, for those who might not know, is both a verb and a noun; at times it is possibly an adjective. It translates roughly to witchcraft, sorcery, obeah, and there is much of it in James’s slave narrative. Teas are brewed which have the power to either drive people mad, or to make people forget the things that haunt them, or to heal a back that has been ravaged by the whip; grave dirt is mixed into potions that have women bleeding to death from every orifice of their bodies; and when the darkness rises up in Lilith, our black heroine with green eyes, the men who have angered her clutch their chests in the throes of a heart attack. Yet the most bewitching aspect of this novel — its greatest act of guzum — is its voice.

•

Historians and linguists have long bemoaned the fact that slave dialect has slipped irretrievably into a place of non-existence; there is no substantial record of it, save for a very few and more than likely untrustworthy instances when Europeans transcribed what it was they thought they had heard. James has performed an ambitious and miraculous act of imagination in “recuperating” this voice to narrate his four-hundred-page novel. This is primarily the story of Lilith, who, though born into slavery in 1785, manages to maintain a fiercely independent spirit. Others want to whip her back into line (literally), remind her of her place on the plantation and in the world, but Lilith becomes the centerpiece of a plot to secure not only her own freedom but the freedom of all slaves. Not for one minute does James allow us to believe that any of this is going to go well.

If one were to be pedantic, there are things we could quibble over in James’s slave dialect recreation, both as sound and as it appears on the page: the skillful use of the Joycean em-dash to render speech; the colourful vocabulary, a sensibility which at times feels very contemporary; the compromises made for the sake of a wider readership — for instance, the word “nigger” in preference to the more distinctly Jamaican “nayga”; the anachronisms sprinkled throughout: Gorgon tells Lilith in one section, “Say dat over and over till it turn into sankey and yuh soon start believe it” — this in 1800, forty years before Ira Sankey was even born, let alone penned his book of hymns. In another quite beautiful moment, the night women washing Lilith’s wounds sing a song from a Jamaican pantomime written by none other than Louise Bennett, a writer whose influence James has dismissed in another forum.

I could go on, but does any of this matter one lick? Resoundingly, it doesn’t. What’s more, it is likely that James himself was aware of these anachronisms. He thankfully understands that the big question we must ask of fiction is not Is this accurate? but, rather, Does this work?

James’s imagination is at times disturbingly dark. Indeed, guzum is a dark practice, and The Book of Night Women, like John Crow’s Devil, offers up its fair share of spilled guts, spraying blood, and more perversions than you could find on bestiality.com. I imagine readers will want to look away or put down the book at times, were it not for the other serious achievement here — the novel’s pace. It is no easy task to write a fast-paced four-hundred-page novel, and yet James has done just that. Many will pick this book up, start at page one, and find themselves many hours later, sitting in the same position, reading through to its tragic conclusion.

The end of the novel reveals at last the secret of the voice which has been guiding us through its pages, and this, I must confess, was my only real disappointment. It is not so much the explanation of the voice (which seems reasonable enough) that disappoints me, but rather the fact that James and his editor felt that it had to be explained, as if the omnipotent narrative voice — when it has as much verve and music and personality as the one James has created here — has to be located within an actual character. I rather liked the experience of reading the novel and the voice coming at me with its own authority, without ever deigning to explain itself, as if it was in this act that James had not only magically recreated the dialect, but magically granted its speaker a level of freedom. To explain the voice seems to me to put it back in its place — a failed rebellion. Perhaps that is appropriate.

Reading The Book of Night Women, I could not help but think of parallels with the fiction of Orlando Patterson — that Harvard sociologist who somehow never became the great Jamaican novelist he ought to have become. The refrain in James’s novel — “every negro walk in a circle” — echoes for me Patterson’s concept of The Children of Sisyphus (1964), both of course having to do with the circular futility that the negro in the West Indies was, and oftentimes still is, forced to endure. But more strikingly, Patterson may have been the last writer to make a serious literary attempt at a Jamaican slave narrative, with his Die the Long Day (1972). As has become well-known history, Patterson’s attempt, though well received at first, was brutally savaged by John Hearne’s review in Caribbean Quarterly, titled “The Novel as Sociology as Bore”. Hearne encouraged Patterson to give up any literary ambition he might have had and stick to the academic discipline of sociology. It was advice which, sadly, Patterson seems to have taken to heart. It is unlikely that James’s Book of Night Women will ever suffer such a review, for though this novel is well researched, and draws on both sociology and history, it is in the end indisputably a literary act of imagination, and in this it is wholly achieved.

In any case, were it to ever suffer a review such as the one Hearne gave Patterson, that reviewer would have to live in fear and trembling, worrying each day about the power of Marlon James’s guzum.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, May 2009

Kei Miller is a Jamaican poet and novelist. He lectures in creative writing at the University of Glasgow. His most recent book is the novel The Same Earth (2008).