Kaleidoscope man

By Malachi McIntosh

Denis Williams: A Life in Works: New and Collected Essays,

ed. Charlotte Williams and Evelyn A. Williams

(Rodopi, ISBN 978-90-420-2791-6, 238 pp)

Other Leopards, by Denis Williams

(Peepal Tree Press, ISBN 978-184-523-067-8, 200 pp)

The Third Temptation, by Denis Williams

(Peepal Tree Press, ISBN 978-184-523-116-3, 108 pp)

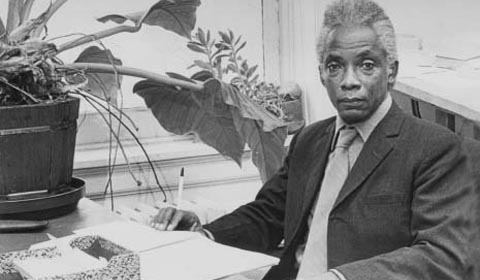

Denis Williams. Photograph courtesy the Society for American Archaeology

Few individuals can claim to have, in a lifetime, filled the roles of novelist, archaeologist, teacher, painter, essayist, and academic, and fewer still can claim to have played those roles across three continents, over seven decades that included stints positioned in metropolises and in rural hinterlands. In the cohort of Caribbean writers who began publishing abroad in the 1950s and 60s, only one managed to live that storied life, the Guyanese Denis Williams (1923–1998).

Williams was all of the above, plus more, his polymathic interests marking him as a singular talent among his contemporaries. This singularity extends beyond his curriculum vitae. Where others left the Caribbean for permanent or near-permanent stints in the United States, Canada, or Britain, Williams was one of the few of his peers to emigrate to Europe and then return to and remain exclusively in his home territory. Where others wrote of an Africa imagined, Williams was one of the few to spend significant time in the continent he wove into his fiction. Where others declared the value of Caribbean art only on paper, Williams was a true, active advocate for Guyanese talent. He was, as we are told in Anne Walmsley’s 1998 obituary, “dynamic, passionate, enthusiastic” — all of those attributes combined to give him the energy to find success and win accolades for himself and others.

And yet, despite all of this, Williams is often neglected. Where his contemporaries like Wilson Harris have monographs and articles dedicated to excavating every sliver of meaning from their texts, Williams’s work has fallen out of print and garnered comparatively little popular or academic interest. This neglect seems, to me at least, entirely undeserved, and the recent re-issue of Williams’s novels Other Leopards and The Third Temptation by Peepal Tree Press, along with the publication of the first edited collection to take him as its sole focus, Denis Williams: A Life in Works, are all steps on the road to equal attention.

With Williams, his strength — the varied, kaleidoscopic nature of his oeuvre — is something of a weakness when it comes to recognition. In order to appreciate everything that the artist produced it would be necessary to have a scholarly breadth that eludes most contemporary specialists. Williams had no substantial production in any one mode: his paintings were his largest artistic output, but by the standards of a lifetime visual artist, his portfolio is small. The questions that hang over anyone who seeks to know Williams in all his forms are where to begin, how to begin, and where to end. The same challenge faces any attempt to draft a satisfactory survey of the artist; where a written introduction to the life and work of a Lamming or a Lovelace would encompass several similar works, and require specialists only from a single field, a survey of Williams faces the challenge of organising commentary on paintings, fiction, archaeological writings, and government art advocacy into a coherent, balanced whole.

•

Denis Williams: A Life in Works rises to this considerable challenge. Edited by the artist’s daughters Charlotte and Evelyn A. Williams, the essay collection engages with all of Williams’s outputs. It is appropriately varied and pulls together personal reflections, critical essays, a full chronology of the artist’s life, as well as a bibliography of primary and secondary texts. As a vanguard text in Williams studies, it is merely a route, rather than a roadway, into his work — but it traces many potential avenues for future studies to follow.

The editors seem fully aware of their pathfinder status. The collection is interwoven with both implicit and explicit calls for further study and, in their introduction, the editors actively position the text as necessary and initial, rather than supplementary and definitive. They state: “while his contributions in particular fields have been acknowledged, [Williams’s] work as a whole has not to date been comprehensively documented and the interconnections have been insufficiently rehearsed”; and they end: “Williams’s contribution is substantial, significant, and lasting, and we offer this documentation of his life’s works for the official record: it will be for others to critically explore aspects of this legacy.”

What follows is broadly divided into essays on Williams’s paintings, his novels, his work in Africa, and his archaeological and art advocacy in Guyana. Like many collections of this kind, quality varies from piece to piece. The overarching strength is the way the many considerations of different aspects of Williams’s life overlap, allowing disparate essays to stack up into an insightful whole. If there is a single, transcendent weakness, it is that the pieces tend to veer more towards commentary than analysis — that they feature more unalloyed praise than balanced assessment.

Evelyn Williams’s opening essay, “The ‘Uncanny-Potency’ of Art”, excellently illustrates these twin tendencies. While offering an interesting consideration of, among other things, Denis Williams’s relationship with his status as a “West Indian artist,” the essay also at times offers the unnecessary gloss of florid yet somewhat insubstantial prose. So while E. Williams reveals that D. Williams “identified himself first and foremost as an artist” rather than a regional talent, and that his acclaimed painting Human World (1950) was seen as a curiosity because of its lack of an ostensibly Guyanese character, she also strays into what I would characterise as a degree of descriptive excess. For example:

The paint medium itself and the marks made have the power to discharge unconscious expression onto the canvas. The artist imparts an intimate record of the substance of his innermost psychic stress. This is tethered to the painting during the process of its creation. The sentience behind each move is fixed in the memory of the brushwork.

This sort of description, peppered throughout the essay, does not detract from the piece’s insight, but it does interrupt its flow. The same can be said of some panegyrics that crop up throughout the collection, from Wilson Harris’s statement that in the composition of Williams’s Painting in Six Related Rhythms “each application of colour was a test of his own genius” to Vibert C. Cambridge’s claim that in 1950s London Williams “had achieved stellar status as an artist” and “attracted the attention of icons such as Salvador Dalí” — an assertion that seems to contradict Evelyn Williams’s earlier description of her father’s artistic career.

It is perhaps natural in a collection of this kind to frequently praise the scale and vision of the underappreciated artist’s endeavour; and yet, in this case, it seems entirely unnecessary, simply because Williams’s works when presented speak for themselves. The strongest essays give Williams’s efforts in his many fields some breathing room or offer commentary that deepens our appreciation of their brilliance, rather than proclaiming that brilliance at length. For me, the best of the batch are Andrew Lindsay’s “Preparing the Palette: The Artist in Words”, which quotes heavily from Williams’s unfinished third novel The Sperm of God; Louis James’s “The Closeness of Profound Curiosity”, which compares Williams’s work to Wilson Harris’s; and Charlotte Williams’s “A Young Man with a Hope”, which — combined with Anne Walmsley’s reprinted Guardian obituary, “He Lived His Life Totally”, and Stanley Greaves’s “Meeting Denis: A Mind Engaged” — gives a wonderful overview of Williams’s life at home and abroad.

There are other high points. Jennifer Wishart and Evelyn Williams’s “The Island of Guiana” and (CRB editor) Nicholas Laughlin’s “As It Was in the Beginning” offer the non-specialist concise introductions to Williams’s archaeological efforts. Both essays are enlightening reads. (The latter, a review of Williams’s Prehistoric Guiana (2003), first appeared in the August 2005 CRB.) The inclusion of copious colour reproductions of Williams’s paintings, the aforementioned full bibliography, and a straightforward chronology of Williams’s life are also of particular value to anyone who would undertake further study of his career.

There are some additional things I would have liked to see. Ulli Beier’s essay on Williams’s work with the Òsogbo Art Workshop in Nigeria, a reprint from his Twenty Years of Oshogbo Art, is frustratingly unspecific about what exactly Williams did while in Nigeria, and would have benefited from a tailored revision. Within the section of reproductions the only photographs we have of Williams himself are either unclear or shots of his back. In an era of instantaneous Google image searches, this is perhaps not the problem it would have been in the past, but it is nonetheless a loss for a book that includes reproductions of several painted self-portraits and which seems intent on presenting all aspects of the artist’s life. Lastly, despite the call in the introduction for more thoroughly interconnected considerations of Williams’s work across disciplines, on the whole, the essays tend to favour chronological survey and juxtaposition rather than deep interdisciplinary analysis.

Nonetheless, and despite these minor quibbles, it seems almost impossible that a reader could complete this volume without gaining a deeper insight into, appreciation of, and curiosity about Denis Williams and his varied works. Based on Evelyn and Charlotte Williams’s introduction, their aim was nothing more than this, and if we use that aim as our criterion for assessment, it is difficult to see this collection as anything other than a success; one that, in the reading, inspires a strong desire to go deeper, to know more, and to expand upon all presented.

•

For those who would endeavour to act on the inspiration of A Life in Works and dive deeper into the artist’s fiction, Peepal Tree’s recent re-releases of Other Leopards (1963) and The Third Temptation (1968) are ideally timed. Both editions begin with accessible and comprehensive introductions by Victor J. Ramraj, and both texts are confounding, complicated, and intriguing fictions from a man who dabbled successfully in experimental narrative.

The novels were written within the 1958–1968 period when Williams lived in Africa, but only Other Leopards engages with the African experience — specifically, the experience of the displaced Caribbean man on the continent. The novel takes place in “Johkara”, a fictional postcolonial African state that is described as “not quite sub-Sahara, but then not quite desert; not Equatorial black, not Mediterranean white. Mulatto. Sudanic mulatto, you could call it.” The country, a stand-in for Sudan, is home to brewing conflict between the Christian North and the Islamic South, and the novel’s focal point, Lionel “Lobo” Froad, is stuck in the middle of that conflict. Or at least he is at the start.

As the novel progresses it becomes clear that the problems between North and South and Christian and Muslim are a mere framing device and replication of the story’s central conflict: that between Lionel and himself. What begins as a wide focus, taking in the people, their prime minister, and the country as a whole — what seems in the first few chapters to be a novel with a panoramic vision — narrows as the pages progress, the book’s lens zooming in, by the end, on just four characters: Lionel/Lobo, his black Guianese lover Eve, his white Welsh lover Catherine, and his white boss Hughie King.

The novel begins, like many Caribbean novels of its time, with an identity crisis. The main character describes struggling with “Lionel, the who I was, dealing with Lobo, the who I continually felt I ought to become.” A confused Caribbean central character who seeks resolution of an identity crisis though Africa often occurs in the literature of the region, and much of the opening of Other Leopards foreshadows the tone and content of Maryse Condé’s Hérémakhonon (1976).

Where Williams’s novel differs from others of its generation — and where its greatest interest lies — is in its step away from a chronological account of Lionel’s battles with his mixed feelings about himself, his white boss, and his black and white lovers. In the novel’s second part, roughly its final third, the narrative takes a sudden, jarring, and decisive shift. Where previously Lionel’s in-betweenness — the kind paralleled in the description of Johkara above — is an undercurrent, the second part of the novel dramatises it fully. The character spends the final portion of the book stranded in a liminal, neither-here-nor-there desert space. The linear movement of the narrative splinters, and we are treated to a stream of consciousness performance of the identity issues presented earlier. In one decisive move, Williams slips into an experimental mode that marks a break between himself and his contemporaries and captures the reader’s attention.

•

Williams returned to this experimental style in The Third Temptation, expanding upon it considerably. His second novel is a move away from the overt nature of Other Leopards into more diffuse territory. It charts the events of a single day and night in Wales, with Guyana and the Caribbean relegated to only passing mention. In his introduction, Ramraj describes The Third Temptation as a work that challenges “those assumptions that seek to corral the Caribbean writer within any narrowly defined focus of legitimate concerns.” The themes that have come to be associated with the Caribbean novel — such as identity, community, rural versus urban, home versus abroad — are entirely missing here. Williams is attempting something else altogether.

What that “something else” is, is largely up to the reader to determine. The novel features only a few characters; of them, only Joshua “Joss” Banks and a woman named Chloë engage in conversation long enough to feel real, and even that sense is ephemeral. In this novel, character is only a passing preoccupation: perspective is the central concern. In fact, it could be said that “perspective” is what the novel is actually about. During the single day in Wales we are treated to myriad points of view, the narrative camera zooming up, down, and around the central location, Sweeley Street, and in and out of multiple characters’ minds. We are faced with several unidentified “I”s, the narration itself repeatedly calling attention to the unstable nature of perspective, at one point stating “it is as though from the sanctum of the insulated ‘I’ all the world were thought to be blind; as though this ‘I’ were not itself constantly multiplied on a thousand moving retinas, each from a different angle, and thereby modified.” The pun on I/eye here is one of the story’s focal tropes.

Neither Other Leopards nor The Third Temptation is perfectly executed. In both novels, characters are at best inconsistent and at worst unbelievable. In the latter this is less of a problem, as the characters are mere performers in a much broader spectacle; in the former, with identity as its main theme, stilted dialogue and seemingly unmotivated action can begin to grate. Both novels feature somewhat troubling representations of women. I can see many readers taking issue with the purity of Lionel’s white lover Catherine, repeatedly contrasted with the angry, odious, hyper-sexualised savagery of his black lover Eve. I, for one, wondered about the significance of Lionel’s various thumps and knees delivered to Eve versus his loving, longing caresses with Catherine.

The problems with these portrayals of women are characteristic of writing from this time. Regarding character, it is necessary to realise, as Ramraj notes in his Other Leopards introduction, that “Williams is preoccupied with the generic problems of racial and national identities, less with the psychological truths of personal problems and relationships.” This statement is difficult to challenge and, with a slight tweak of the themes mentioned, applies equally well to The Third Temptation and to his work as a whole.

Williams was a singular talent. From the start of his artistic career, onward through his many shifts in location, medium, and subject matter, he always took a path that was different from that of his contemporaries. Where other visual artists painted Caribbean scenes, Williams painted urban landscapes and abstractions; where writers praised an unknown Africa, Williams questioned where the Caribbean man fit in on the continent; where many intellectuals left and stayed away, Williams returned home. His singularity was expressed in works that are varied, challenging, sometimes imbalanced, but always intriguing. I can only hope that with the publication of Denis Williams: A Life in Works and the re-release of Other Leopards and The Third Temptation more readers will become familiar with both the artist and his art.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, November 2010

Malachi McIntosh is a final-year PhD student at the University of Warwick who has recently completed a thesis on the representation of the Caribbean by its emigrants. His writing has been published in Fugue, the UK Guardian, and The Journal of Romance Studies, and he has just finished a novel, Static.