Out of sight

Judy Raymond on the creative omissions of “Trinidad’s nineteenth-century artist,” Michel Jean Cazabon

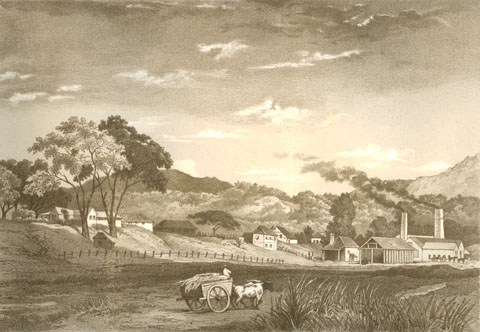

Of the thirty-six images in Michel Jean Cazabon’s two albums of lithographs of Trinidad, only one depicts the sugar industry: Garden Estate, Arouca, from Album of Trinidad (1857). Image courtesy Mark Pereira and 101 Art Gallery

Michel Jean Cazabon (1813–1888) has a special place in the hearts of Trinidadians, for a number of reasons, but not all of them are grounded in fact. Cazabon is often described as “Trinidad’s nineteenth-century artist,” an expression that suggests he was one of a kind. He’s considered a pioneer, and indeed in some respects he was. Even more importantly, we think of Cazabon as one of us. He was a Trinidadian, of mixed race, and his work evokes pride and nostalgia and a sense of pleasing familiarity. We know and recognise the scenes he painted: fronds of bamboo arching over rivers, kite-flying and horse-racing in the Savannah, the stumpy twin turrets of the Roman Catholic cathedral.

But the nostalgia evoked by Cazabon is for a Trinidad that may never have existed. And the more you look at his paintings, the odder they start to seem.

That’s because we look at him as if he were unique. In fact, Cazabon fits firmly into a tradition, and once he is set into this context, his paintings become, if no less idiosyncratic, then at least more understandable.

This is not to say that Cazabon’s pictures don’t have artistic merit, or charm, or that they are not valuable as a record of some aspects of Trinidad in the second half of the nineteenth century. But you have to be careful about the use of that word “record.” Cazabon’s paintings have been looked at and talked about as though he simply set up his easel and painted whatever lay in front of him, without selecting or interpreting his material, when in fact nothing could be further from the truth. He’s sometimes called an historian, another description fraught with pitfalls.

Cazabon was a highly trained and also a highly self-conscious artist — he had to be, given the time and place he worked in. He was romantic, but far from naïve. His paintings are not simply arbitrary appealing scenes he happened to come across, but precisely edited images; not a panorama, but the product of a kind of tunnel vision. His skill is to persuade the viewer to look at his landscapes with the same narrow focus.

•

Cazabon wasn’t the first artist to work in Trinidad and to represent some of what he saw around him. But he was the first professional artist to do so. That is, he was both the first who was academically trained and the first to make a living at his easel. He went to school in England, and later studied art in France and Italy. By the time he came home for good, in 1848, he was thirty-five, and had already worked as an artist in Europe for almost a decade.

On his return, Cazabon advertised his services as a drawing master, and offered to take commissions for portraits and landscapes in watercolour and oils. By 1849 he had begun to receive commissions from wealthy planters such as James Lamont, a Scotsman who owned estates in Diego Martin, and the biggest planter in the island, William Hardin Burnley, of Orange Grove. Another important patron in that period was Lord Harris, governor of Trinidad from 1846 to 1853.

Cazabon occupied an awkward position in society, which must have had an effect on his personality and his work. His family were free coloured people, originally from Martinique, and they owned plantations in south Trinidad. So they were well-to-do, although their social status was hampered by legal obstacles until the mid-1820s, when Michel Jean was in his teens: until then, free coloured people did not have the same legal rights and freedoms as whites, though of course they were far better off, legally and materially, than black people. The Cazabons were slave-owners until not long before they sold their estates at Corinth in 1837. Even after abolition, like everyone else who wasn’t black, they would still have considered themselves superior to their former slaves.

Nowadays it’s sometimes supposed that Cazabon’s paintings of Trinidadians — which show black and mixed-race people and Indians looking attractive and elegant — indicate the natural empathy he felt towards them, since they were his compatriots and he himself was a man of colour.

That may be so, though it’s doubtful. But in any case Cazabon wasn’t painting his pictures for himself, and he wasn’t starting from scratch. He was trained and had worked in a European tradition that he continued to follow faithfully in many respects. Some of the truths of West Indian life couldn’t be fitted into artistic moulds made in Europe, and that’s why they don’t appear in Cazabon’s work.

•

What exactly did Cazabon leave out? Much of the country, in a literal sense: the geography of his work is limited, with few exceptions, to Port of Spain and the valleys around it, and scenes in the north-west peninsula. Travelling around Trinidad in the nineteenth century was extremely difficult; but even so, Cazabon’s range of locations is very narrow. In Port of Spain, he painted mainly public buildings — the churches, the St James barracks, the governor’s residence — and one or two houses belonging to planters. There are seafront paintings at Cobo Town.

But wouldn’t it have been fascinating to see what downtown Port of Spain looked like one hundred and fifty years ago? When Cazabon painted Trinity Cathedral, however, he left out the tenements that surrounded it on two sides.

For one thing, tenements were not picturesque; which, in reference to nineteenth-century painting, is a technical term. Picturesque landscapes drew on the principles followed in the pastoral landscapes of Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin. They were not “beautiful” — a term that implied classical formality and symmetry; the picturesque was less disciplined and regular. Nor did they depict “the sublime” — wild and dramatic scenes that inspired awe.

In his Observations on the River Wye (1782), the Rev. William Gilpin had laid down the principles of an approach to picturesque landscape painting that had been developing since the 1760s. Buildings were not to feature prominently, although ruined Arcadian temples were welcome. Other buildings should be rural and dilapidated, which for Cazabon ruled out town houses and occupied estate houses. Also importantly for Cazabon’s work, the Rev. Gilpin disapproved of landscapes that showed the signs of agricultural cultivation. On artistic grounds, then, Cazabon should omit canefields, sugar factories, and mills — all of which are indeed generally absent from his landscapes. (His view of Garden Estate in Arouca is one of the few exceptions.)

Gilpin frowned, too, on painting people engaged in agricultural work: the industrious mechanic should not appear, although loitering peasants were acceptable. But the presentation of innocuous bucolic scenes presented special challenges to an artist working in the West Indies. The denizens of the Trinidadian countryside were not even native to the scene. They were Africans who had been brutally uprooted, transplanted, and enslaved, and recently arrived indentured Indian workers who lived under almost equally degrading legal conditions and possibly even more squalid physical ones. Neither of these groups suggested a peaceful pastoral existence unchanged for centuries, to say the least. Worse, in a society whose elite had lived for decades in constant fear of slave uprisings, idling peasants were likely to be perceived as threatening rather than charming. No wonder black men scarcely feature in Cazabon’s landscapes, especially by comparison with the number of blanchisseuses and marchandes.

As for the Indian indentured workers, where did they fit in? “At the bottom,” was the immediate answer. Nineteenth-century writers remark on how ragged the Indians were and in what wretched conditions they lived, on or off the estates. They were looked down on even by those who had until recently been slaves.

It’s very hard to square the written accounts with Cazabon’s pictures. The painting originally known as Coolie Group (now politely rechristened East Indian Group) shows a serene couple and their child (who is oddly wizened; Cazabon was by inclination and ability a landscape painter, not a portraitist). Immaculately dressed — the man’s tunic and rather skimpy dhoti are white — they stand outside a spick-and-span cottage. Like Cazabon’s elaborately outfitted mulatto ladies, they are contented, docile, and eager to conform to the standards of the ruling class. The non-white Trinidadians in Cazabon’s work may have exotic aspects, to European eyes — their skin tone, the Indians’ clothes, the black girls’ headties and bangles — but not alarmingly so. They, like the painter and his customers, do not wish to disturb the status quo.

•

To judge the extent to which Cazabon edited reality in his images of the Trinidad of the nineteenth century, it’s useful to compare them with the work of an earlier artist.

Richard Bridgens was an Englishman who came to Trinidad to run a plantation, though he was what we would call a designer by profession (he designed the first Red House, the one burned down in the 1903 Water Riots). He arrived in Trinidad in 1826, and worked a generation before Cazabon, in the last years of slavery. He published several books, one of which consists of images of Trinidad: West India Scenery: with illustrations of Negro character, the process of making sugar, etc.

Bridgens showed what Cazabon discreetly omitted. He was fascinated by what he saw when he came to Trinidad; so he drew it. And of course what was strange and interesting and different, to a newly arrived Englishman, was that the majority of the population were black slaves. Trinidad had a sugar economy run on the labour of Africans; so Bridgens recorded that information.

Yet it would be hard even to guess at those fundamental, glaring facts from Cazabon’s paintings.

Bridgens was not the first to show scenes like this. Earlier, English artists working in Jamaica had found a way to accommodate the images of the sugar estate within the framework of the picturesque. It was this combination that produced what has been christened “imperial georgic”: scenes of agricultural labour set against a tropical landscape and carried out by African slaves.

But just as the pastoral English scenes of the early nineteenth century had omitted the signs of working-class unrest and the Industrial Revolution, so Cazabon glosses over the effects of slavery and sugar cultivation on the landscape and the people of Trinidad. Although he set up his easel a decade after the abolition of slavery, by then the situation was if anything more problematic as a subject for art.

Bridgens had shared the racist views of his kind, and was forthright about them in his pictures. He wasn’t embarrassed by slavery. Racist attitudes had actually hardened around the time of emancipation, as old certainties crumbled and the society struggled with new questions of race and class. As Cazabon’s patron Lord Harris famously observed, “A race has been freed, but a society has not yet been formed.” No one knew what would become of the thousands of former slaves who had refused to stay in their allotted places on the plantations, or the Indians who had followed them — no thought had been given to the eventuality of their wanting to stay in Trinidad once their contracts expired, but there they were.

The precedent set by Bridgens and the Englishmen who painted eighteenth-century Jamaica says much about Cazabon, because he didn’t follow it. If he didn’t paint free Africans or indentured labourers at work in the canefields, that was not because it was generally considered a shameful topic, or not a suitable subject for art. His omissions, like everything else about his paintings, were the result of a calculated choice. His own artistic tastes and training accommodated the social attitudes of the planter classes he came from and for whom he painted — he may have largely shared those attitudes, in fact. And even in his own day, like the picturesque European landscapes that inspired them, his paintings harked back to a tranquil, uncomplicated time that had never really happened; they embody not so much nostalgia as wishful thinking.

To point this out is not to detract from his artistic skill, but to acknowledge it. Cazabon’s artistry lay not only in technique but also in his extremely careful composition and choice of subjects. Because his work is so accomplished, it’s easy to be so beguiled by his paintings that you hardly notice what isn’t there.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, November 2010

Judy Raymond is the editor of Caribbean Beat and writes a parliamentary column in the Sunday Express. She has written two biographical studies, Barbara Jardine: Goldsmith (2006) and Meiling: Fashion Designer (2007), and is working on another, of the nineteenth-century artist Richard Bridgens.