Belonging to in-between

By Jerry Philogene

Wrestling with the Image: Caribbean Interventions,

curated by Christopher Cozier and Tatiana Flores

Art Museum of the Americas, Washington, DC; 21 January to 10 March, 2011

(Supported by the World Bank Art Programme in partnership with the Organisation of American States, the Inter-American Development Bank,

and the Caribbean Community Secretariat, part of the About Change emerging artists’ programme)

Wrestling with the Image: Caribbean Interventions,

ed. Christopher Cozier and Tatiana Flores

(Artzpub/Draconian Switch, 107 pp; downloadable)

I Am Not Afraid to Fight a Perfect Stranger (2009), by John Cox; acrylic on canvas, 167.6 x 274.3 cm

On 16 January, 2011, at 5.30 pm, Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier returned to Haiti after twenty-five years’ exile. What does Duvalier’s return mean for a country still reeling from the effects of a devastating earthquake one year before, on 12 January, 2010? What does Duvalier’s return mean for a country in the throes of a cholera epidemic? What does it mean for a country in the grips of violence too traumatic to mention publicly — the rape of its female citizens? What do I make of the dozen or so “loyal supporters” who greeted him at the airport as if he were the returning prodigal son? Does his return scream to the international community that Haitians have a short-term memory, a memory distorted and corrupted by hunger, poverty, and death? What does his return mean? Moreover, does he have the right to return?

Wrestling with the Image: Caribbean Interventions, an exhibition which opened on 21 January at the Art Museum of the Americas in Washington, DC, helps me make sense of Duvalier’s return, and what it may mean for Haiti and Haitians. Curated by artist Christopher Cozier and Tatiana Flores, professor of art history at Rutgers University, Wrestling with the Image asks provocative questions about what it means to belong to the Caribbean, and what it means to no longer belong and yet return to the Caribbean. How do metaphorical and physical returns provide fodder for the creation of cultural production?

Featuring the work of thirty-six contemporary artists from twelve Caribbean countries, Wrestling with the Image presents an arresting balance of decisiveness and inquiry at a time when the “Caribbean” art exhibition seems de rigueur in the United States. The Studio Museum in Harlem, El Museo del Barrio, and the Queens Museum of Art are currently planning a triple-site show in New York City. In 2007, Tumelo Mosaka curated Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art at the Brooklyn Museum, a beautifully installed exhibition featuring the work of over forty emerging and established artists of Caribbean descent. What troubled me about Infinite Island, besides the very specific and dogmatic categorising of the artists, was the way the Caribbean was signalled as a single, enclosed island, albeit with infinite possibilities.

Wrestling with the Image suggests that the idea of “the Caribbean,” or a “Caribbean” art exhibition, is fraught with stereotypes, inconsistencies, and misconceptions. Cozier and Flores present a seemingly quiet show filled with richly complex pieces, ranging from photography and video to prints and painting, installation, and sculpture. In this gathering of a wide range of artistic production, there are striking conceptual similarities among the artworks; we see within them a compelling consideration of memory, space, and locality. Wrestling with the Image asks how artists alter the meaning and the manner in which “Caribbean” cultures and identities are recorded and understood, both inside and outside the region. How do artists engage with, re-imagine, and transform Caribbean diasporic cultures in their creative practices? As bilingual artists, in what visual language do they exist in the diaspora? When they speak of diaspora, where are they speaking from? How does that affect what they say, and in what language it is spoken? One by one, the artists provide provocative elucidations to these inquiries.

Exploring various themes addressing the specificity of the “local,” while contemplating the abstraction of the “displaced” and the practicalities of “home,” the artists in this show help refashion what it means to be from the Caribbean. Nicely balanced between established artists like Richard Fung (Trinidad and Tobago/Canada), Joscelyn Gardner (Barbados/Canada), Terry Boddie (St Kitts and Nevis/US), Roshini Kempadoo (Guyana/Trinidad/Britain), and Nicole Awai (Trinidad/US), and newcomers like Marlon Griffith (Trinidad) and Marlon James (Jamaica), Wrestling with the Image gives the viewer a full sense of the artistic production that drives the creativity of people of Caribbean descent.

•

Bagasse Cycle 1 (Bagasse) (2009), by Charles Campbell; acrylic on canvas, 550 x 220 cm

Entering the gallery, you are first greeted by Bagasse Cycle 1 (Bagasse) (2009), a large-scale black-and-white painting by Charles Campbell. The fluidity of line and solidness of paint are reminiscent of the abstract expressionist tradition. Embedded in the frenzied and telling lines lie the markings of Dutch slave ships which carried human cargo to the Caribbean to create the bagasse that remains after sugar cane stalks have been crushed to extract their juices. Unabashedly, Bagasse Cycle 1 refers to the legacies of slavery and colonialism.

Framed in two sections in a side corner is John Cox’s beautiful, deeply textured painting I Am Not Afraid to Fight a Perfect Stranger (2009) — part of Cox’s ongoing Boxer series, which presents the artist in various sportsman personas. In the masculine pose of the two figures, we sense the intensity between the fighters: a virile intensity that lies at the definition of a hegemonic masculinity; a hegemonic masculinity that speaks to the spectacular performative public selves illustrated in Cox’s series.

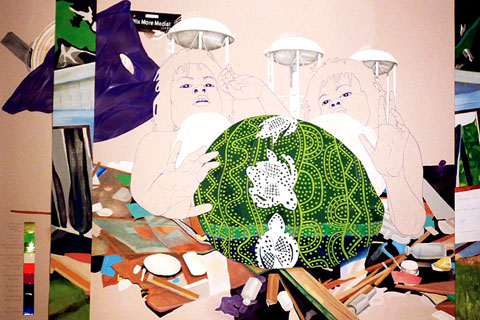

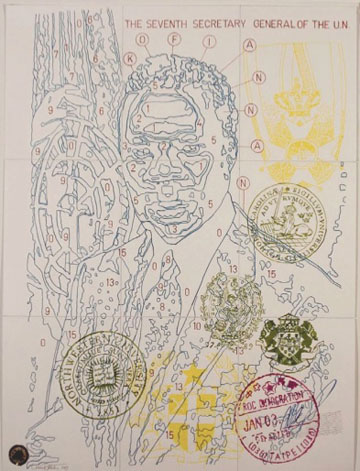

Many of the works in the exhibition feature personal narratives and biting political critiques. Nicole Awai’s stunningly light and beautiful work Specimen From Local Ephemera: Mix More Media! (2009) provides a vocabulary to speak about conceptual and formal attention to colour, line, and form. Appearing as a “doubled self,” Awai positions herself as a complicated figure who can, simultaneously, tell the story of the public and the private. Jean-Ulrick Désert’s The Seventh Secretary General of the UN (2009) — in which orderly and intricate drawings of passport stamps and paint-by-number designs come together to form a likeness of Kofi Annan, the Ghanaian diplomat who served as head of the United Nations — speaks to the artist’s composed yet potent critique of a “Foucauldian governmentality” that has been imposed on various Caribbean countries.

Detail of Specimen from Local Ephemera: Mix More Media! (2009), by Nicole Awai; graphite, acrylic paint, and nail polish on paper, 96.5 x 127 cm

The Seventh Secretary General of the UN (2009), by Jean-Ulrick Désert; ink and rag on paper, 120 x 90 cm

What excites me is that Wrestling with the Image is not a “Caribbean” exhibition, as Cozier remarks in his catalogue essay. These are artists whose cultural heritage, in part, can be traced to the Caribbean. But they are influenced by myriad cultures, traditions, languages, and histories, and have become part of a transnational diasporic identity. Many still reside in the Caribbean, but their work speaks to the transnational routes they have chosen to take or not take, illuminating the complex issues and shifting strategies of living diasporically, of creating diasporically, and creating in a visual language that takes into consideration various locations of existence. The works in the exhibition speak to the fluidity of diasporic subjects and create a lingua franca, a visual multilingualism that blends Creole Caribbean, French, Japanese, German, Dutch, English, and other cultural elements, and reveals the centrality of memory to the formation of cultural identity.

Drawing upon this visual multilingualism, these artists create a polycultural visuality that illustrates the multiplicity of their identities: identities formed and informed by memories of the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, St Kitts and Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago — as well as contemporary formulations of each Caribbean island in North America, Europe, and Asia. Using culturally loaded images and materials to evoke this visual dialect, their works are reactions to the complexities of living in the Caribbean diaspora, living in endezo — a Haitian Creole word, meaning “to live between two waters” — that “in-between” space, the hyphen, the space of negotiation.

Ebony Patterson’s large-scale digital print Entourage (2010) suggests a voyeuristic fascination with dancehall and the “gangsta” attitude that is so necessary to “pon de replay.” Her seductively posed females and thuggish-looking men pose against a black and white floral-print backdrop, while gazing defiantly across at Marlon Griffith’s self-styling Powder Box Schoolgirl (2009) images. His Louis, Tribal, and Blossom are fascinated with “bling” and its Caribbean manifestations. The three photographs of individual school-age girls — decked out in their school uniforms, proudly announcing their membership in a particular existential space of “self-reliance” or “tranquillity” — are taken at close range. Griffith does not allow us to see the full faces of his models — knowingly and intentionally, we wonder? Instead, our gaze is consumed by the tattoo-like markings on the necks and chests of the models, made with stencilled talcum powder. They remind us of the intense “powdering” of the neck fresh after a bath or shower and the tattooing of the “LV” logo, courtesy of Louis Vuitton. Patterson and Griffith’s pieces speak to an explicit and complicit self-(re)fashioning and self-(re)presentation, and comment on both the global commodification of Caribbean culture — such as Jamaican dancehall — and, in turn, a Caribbean fascination with global commodities.

Entourage (2010), by Ebony G. Patterson; digital print, 204.5 x 306 cm

Louis, Tribal, and Blossom (2009), by Marlon Griffith; digital prints, 121.3 x 80.6 cm each

Detail of Louis (2009), by Marlon Griffith; digital print, 121.3 x 80.6 cm

While commenting on specific cultural nuances, Wrestling with the Image steers clear of the formulaic. We do not have images with an excess of brightly coloured flora and fauna, ganja-smoking Rasta men, picturesque market women, or affected vaudou imagery. However, we do have images of palm trees. Clearly referring to the problematic visual taxonomy of the palm tree as an icon of “the tropics,” Blue Curry’s video Discovery of the Palm Tree: Phone Mast (2008) slowly and hypnotically draws the viewer’s eyes into the screen to discover the “fakeness” of a telephone pole masked as natural flora. On this quotidian island, technology must not interfere with the tropical landscape. The nineteenth-century island imaginary must not be hindered by twenty-first-century machinery. Curry’s manipulation speaks to the manipulation of the idea of “the Caribbean.”

In his video Islands (2002), Richard Fung produces a critical investigation of the invisibility of visibility. In his search for his uncle Clive — who was an extra in the Hollywood film Heavens Knows, Mr Allison (1956), filmed in Tobago but supposedly based in the South Pacific — Fung critiques Hollywood’s disavowal of difference and the absence of any cultural specificity. His search for a human presence resonates keenly with the theoretical ideas buttressing Wrestling with the Image. For director John Huston, it seems, to be from the South Pacific was the same as being from the Caribbean. In Heavens Knows, Mr Allison, Uncle Clive’s Asian-Trinidadian self is transposable with the numerous cultural and ethnic communities that make up the South Pacific islands.

Installation view of Discovery of the Palm Tree: Phone Mast (2008), by Blue Curry; digital video, dimensions variable, duration 00:02:17

Still from Islands (2002), by Richard Fung; digital video, dimensions variable, duration 00:09:00

Marlon James also addresses a search for meaning within representation. His large-scale photographs Jabari (2007), Mark and Gisele (2007), and Stef2 (2010), depicting friends and fellow artists, remind us of the thorny nature of image-taking and -making for people of colour, especially those who for decades functioned as anthropological specimens. In these images, James has reclaimed that photographic space, turning the gaze outward, challenging the right to look and the right to be looked at, processes which undermine colonialist logic and its systems of power and discourse of invisibility. What better place than film and photography to create provocative images to talk about complex understandings of power, race, and visibility?

In Nadia Huggins’s photograph The Garden, (2005), our eyes are drawn to the rose print of the blanket on a mattress. Two fully clothed women lie side by side, very close to the edges of the bed, with what seem like miles between them. Our view is from their torsos down to their blemished legs and age-worn feet. Their seemingly restful poses trigger our fantasies about the comforts of home, but also a sense of the discomforting, uneasy, and alienating space that home can be. What accounts for the sense of alienation that jumps out of the photograph? What these individual yet collective stories remind us of is the importance of the politics of memory as semantic practices that produce a grammar of subjectivity.

The Garden (2005), by Nadia Huggins; digital print, 29.8 x 39.4 cm

As Cozier announces in his catalogue essay, this “is not a survey or inventory of linguistic, ethnic, cultural or national modes.” Individually and collectively, the works gathered in the exhibition highlight the cultural mixing, aesthetic diversities, and critical voices that reflect the influence of international contemporary art influences. But, more importantly, the work emerges from the distinct circumstances of the Caribbean itself, an archipelago of islands always in process. As I wandered through the gallery, I was reminded of Stuart Hall’s central thesis in “Cultural Identity and Diaspora”. Hall tells us that “identity as a ‘production’ is never complete; it is always in process, and always constituted within, not outside, representation.” The artists of Wrestling with the Image speak clearly to Hall’s brilliant thesis. The works gathered here invoke various experiences of travel, diaspora, memories of locations, histories, and people, and cultural practices that simultaneously diverge and intersect at interesting moments and not-so-familiar places.

Cozier and Flores have created a representational space that invites us to reflect on innovative artistic forms as inquiries that can inspire a rethinking of what it means to belong to the Caribbean. As Flores writes, this work “allows us to glimpse into the multifaceted contemporary experience of the Caribbean.” The show also helps me “wrestle” with the return of Duvalier to Haiti, a seemingly smooth entrance for what is sure to be a noxious sojourn. Ultimately, Wrestling with the Image allows us to realise the conscious and specific negotiations that invest Caribbean post-colonial subjects with social and cultural capital.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, January 2011

Jerry Philogene is assistant professor in the American Studies department at Dickinson College. She specialises in twentieth-century African-American and Caribbean visual arts and cultural history. She is currently working on a book manuscript, Travelling Diasporically: Images of Haitian Cultural Citizenship, which examines the relationship between visual arts, cultural citizenship, and Caribbean/Caribbean American cultural production.