Ghetto geographies

By Nadia Ellis

DanceHall: From Slave Ship to Ghetto, by Sonjah Stanley Niaah (University of Ottawa Press, ISBN 978-0-7766-3041-0, 260 pp)

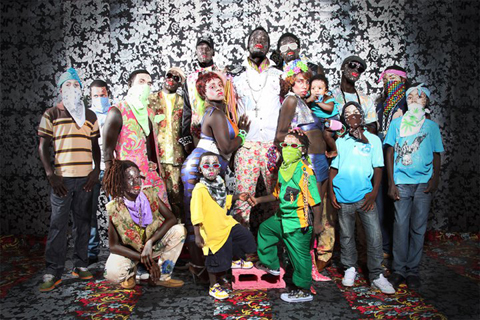

Entourage (2010; digital print, 204.5 x 306 cm), by Ebony G. Patterson, from the exhibition Wrestling with the Image: Caribbean Interventions, at the Art Museum of the Americas, 21 January to 10 March, 2011. Image courtesy the artist

I’m pretty much convinced by Sonjah Stanley Niaah’s concept of performance geography, as explored in DanceHall: From Slave Ship to Ghetto. By which I mean that I find the necessity of its articulation utterly compelling, I am intrigued by its various theoretical propositions, and find its resonances with other accounts of history and performance useful. Whatever questions remain are only of the sort that accompany a fresh articulation: answering them wouldn’t be the point. The point is to prompt the questions in the first place.

And so Stanley Niaah argues that we can think about Jamaican dancehall in relation to black performance practices ranging from the limbo on the deck of the slave ship to the juke joints of the American South and raucous parties in post-Apartheid South African townships. What these spaces have in common is their intense compression and their literal and figurative marginality in the landscapes of oppressive regimes. Dancehall participants’ relationship to space teaches us about black people’s ability to create out of confinement. The geographic course that dancehall charts from Kingston to Africa to Europe to Asia and back again teaches us about the new circuits of the Black Atlantic, which were never so unidirectional as we imagined them to be, anyway. Performance becomes place-making: a street becomes a stage because Sadiki and Bogle dance on it. The echoes of performance spaces across black cultures settle here on the ghettos most prominently, but Stanley Niaah’s interest in the ritualisation of dancehall performance leads to evocative images beyond the city streets:

Kingston Harbour operates as an aquatic drum on which the sounds from the inner city are amplified and sent out to the world. While this is a figurative rendering of how reggae music and later dancehall spread globally, it is also a visual representation of the sacred drum, the echo chamber that Kingston Harbour has become for Kingston’s sound systems. Kingston, with its backdrop of mountains overlooking the natural harbour, is both physically and metaphorically the amphitheatre in which daily life is performed for both the self and the world as its spectator.

Dancing about architecture — which, by the way, is what one of dancehall’s queens, Stacey, is known for: mounting edifices of speaker towers, traversing ceilings like a super-hero, claiming space with her body, and so making a dance of architecture, embodying the interface between the body and the building. Limning the surface of the built environment, marking her supremacy over these structures while also drawing attention to the cruel effectiveness of the city’s planners. This is one of the things Stanley Niaah reminds us of when she tells us about Stacey dancing on the rafters at the British School Uniform party in 2003. (Really, how to summarise dancehall’s traversal into kitsch? See Rex Nettleford on Creole fancy dress parties; cf. dancehall’s tipping point from the fanciful into the queer.)

But what to make of these claims of dancehall’s rituals? We all believe them, certainly. We know in our bones that what’s happening in these streets constitutes something meaningful beyond play or dance. And we know for sure that there was a dance called the limbo on the slave ship that ritualised the trauma of crossing, and that in the late 1990s and again in the early 2000s a dance called the limbo was created for the dancehall by Bogle (R.I.P.). We know that music and dance have long been the material accompaniments to spiritual ritual, the evidence of the unseen, the maker of the unseen, what brings it into being in the first place. But one does ask while reading Stanley Niaah’s text whether, really, the cramped quarters of a downtown Kingston neighbourhood are “just like” the holds of a slave ship. Whether the nighttime dances held on any given day of the week in Kingston are “reminiscent” of nighttime meetings held by slaves to plan revolt. How exactly?

Stanley Niaah’s choice of words here — “reminiscent,” for example — is telling. Was she there? Yes and no, right? This is the thing about trying to document the historical resonances of contemporary black practice. The gaps in the archive mean that at some level it’s about being transported; it’s about, in a sense, faith. We don’t have enough in the documentary material to go on. What we do have on paper is mediated — the Dutch writer John Gabriel Stedman’s 1796 account of Surinamese slave culture comes up a few times, for instance. What we have in the body, Stanley Niaah’s terrain, becomes a separate archive, a repertoire of history, the etchings of which must always at some level be mysterious.

Stanley Niaah’s knowledge of the elements of dancehall over the last two decades, however, is firsthand and encyclopaedic. Much of the value of this book is to be found in the way it documents the details of a culture so swiftly moving that it can seem impossible to document at all. Precisely because of dancehall’s pace, aspects of the culture from only a decade ago take on the quality of artifacts. In collecting these, Stanley Niaah becomes an archivist of the contemporary, making certain all those flourescent red, green, and gold posters advertising the latest bashment don’t just get papered over into oblivion. She lists, for instance, all of the major street dances to be attended on a weekly basis in 2004. These are different from the list of street dances to be attended in the summer of 2007. And not the same, of course, as the dance moves themselves invented by the likes of Bogle and more recent dance crews like Ravers Clavers — these are listed, too.

The space between the list of dances and what it feels like to be at the dances themselves is often where this book lives. This is true, arguably, of any academic project on dancehall. Through deep and careful study, Stanley Niaah is able to bring the details of the culture to academic scrutiny. But isn’t the point of dancehall in part its inconvenient repudiation of responsibility, at least as responsibility is constructed by local arbiters of decency, or tourist boards, or a whole heap of the ideals of Western liberalism? Surely, as Stanley Niaah is able to show, the whole apparatus that we call dancehall — the production system, the DJs, the dancers, the sound systems and selectors, and the relationship of all of these to political and economic systems in Jamaica, and in the vast and varied touring markets of North America, Europe, and Japan — is complex and, yes, disciplined in its own right. But it is dancehall’s tendency to break out just at the moment when it seems to be getting a foothold on political respectability. Buju will refuse to apologise. Vybz will start bleaching. It is precisely dancehall’s refusal to make nice that keeps it compelling; it is the perennial prodigal, beloved in its waywardness.

Which is why when we take it up in academic discourse there’s sometimes a strain. An example:

. . . in his single “Likkle and Cute” the DJ Frisco Kidd (1997) chastises a woman who has not taken enough care to maintain the health and strength of her vagina and advances a discourse about the “good body gyal” who has no need to use alum to reduce the elasticity of her pudenda, as those who engage in too much sexual activity do.

For a certain portion of Stanley Niaah’s readership, as soon as the words “Likkle and Cute” appear on the page, a beat will start thumping in the brain. A whiny voice will jump on top of the riddim. A whole other time and place will emerge fully formed in the brain. Wrenching us back to the slightly less revelrous task at hand are words like discourse, chastise, and — let’s face it — vagina. Anatomically correct, and yet: when is the last time anyone heard female sex organs referred to in dancehall by a word not beginning with p? (And no, the Latin pudenda doesn’t count.)

I’m not suggesting there is any easy way to discuss Frisco Kidd’s admonishments about vaginal elasticity. Indeed, I recognise and affirm Stanley Niaah’s moves here. She circumvents (hysterical) tendencies in discussions of sexually explicit dancehall lyrics by situating the lyrics in a larger network of other discussions about sexuality. She avoids complicity with sexist imperatives by refusing to reproduce the language of their terms. And she walks a linguistic tightrope, conforming to the academic conventions to which her book is accountable while giving space to a set of discourses not generally scrutinised with the imprimatur of the university press. All of this is necessary. But I linger here just to gesture at the inherent challenges of writing about dancehall. Writing a book about this recalcitrant strain of popular culture means yoking words to incommensurate registers; sometimes the writing feels the strain. (To be clear, I experience this strain all the time, not least on the occasion of this very review.)

But these moments of disjunct are perhaps necessary, part of the displacements which Stanley Niaah describes, as dancehall continues its career, moving far beyond the spaces of its birth. And in any event they are repaid by the exhaustiveness of Stanley Niaah’s account, the capaciousness of her theoretical investments, and the moments of ethnographic detail. There is a sense that we’re in the company of someone who can really show us what’s been going on, can introduce us to many of the major players, can stay up later than we can, can navigate the streets with smarts, wit, and respect. She’s a great guide down dancehall’s many side streets.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, January 2011

Nadia Ellis is from Jamaica. She teaches literature at the University of California at Berkeley.