Enigmas of exile

By Nicolette Bethel

Running the Dusk, by Christian Campbell

(Peepal Tree Press, ISBN 978-1845-231-552, 84 pp)

A Light Song of Light, by Kei Miller

(Carcanet, ISBN 978-1-847771-03-2, 80 pp)

Far District, by Ishion Hutchinson

(Peepal Tree Press, ISBN 978-1845-231-576, 96 pp)

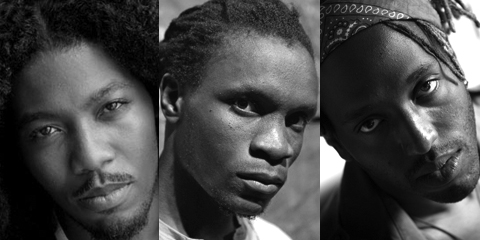

Christian Campbell, Ishion Hutchinson, and Kei Miller

Many months ago I agreed, somewhat against my better judgement, to take on the task of reviewing three books of poems by young Caribbean men. I was most reluctant. I found the task intimidating. These books — Christian Campbell’s Running the Dusk, Kei Miller’s A Light Song of Light, and Ishion Hutchinson’s Far District — pushed me outside my critical comfort zone. They are books written in exile by young twenty-first-century Caribbean men; and I am a Caribbean woman from the end of the last century who has chosen not to leave her homeland for literary purposes, in large part because I believe that it should no longer be necessary. (Whether it is or not is entirely a different story, and a subject for another day.)

The task has taken me longer than it should have done for any number of reasons, the only one really relevant here being my profound mistrust of my own ability to make sense of these books, to say something resonant about these collections. But time has been, as usual, its own silent magician, and sense has been made by it for me. These books are remarkable. So is the fact that they are the product of three voices from three different parts of our region and from the world.

Campbell’s Running the Dusk is a book that has been a long time in coming. (I trust readers will forgive my partisanship in this; but I am Bahamian, and so is Campbell, and we have had to wait till the twenty-first century, fifty years later than our big cousins to our south, to see elements of ourselves on a page as polished and as wide-flung and as acclaimed as his.) It is a collection of poems by an author who sings his hybridity, his pan-Caribbeanness, while at the same time grounding his world in these limestone fragments we call the Commonwealth of the Bahamas. I trust readers will also forgive my partiality for poems such as “Pardon I Soldier” and “Old Man Chant”, and of course the incomparable “Goodman’s Bay II”, for what they engrave in the literature about our forgotten country. From the Arawak Cay fish fry to the Panama Canal to Haiti, these three poems peg out a blueprint for a Bahamian literary existence. For instance, in “Pardon I Soldier”, Campbell not only captures the essence of a place — “Conch fritters, spill / Guinness, skyjuice, / herb, piss, smoke” — but also of a psyche: of the danger that lives just beneath the skin of our picture-postcard destination, of the anger that young men carry, of the near-inevitability of physical contact turning deadly. To wit:

But he pass, cool rebel,

no clash, no clash.

From “Pardon I Soldier” Campbell turns to sing a praise chant for the generation of Bahamian men gone before. “Old Man Chant” is a poem that drives me to the brink of tears each time I read it. I think the reason lies in the respect this young poet pays to the old men who paved the way for him, even though their paving stones are fading and their names all but gone. The reason also lies in Campbell’s recognition of the strengths and the flaws of this generation, in the complexity of the reality, and in the truth of it all — the fact that all Bahamians of a certain generation have known men like this, “who smell of rum / and tiger balm, sometimes Limacol / and the musky smell of Old Spice”:

You men with perpendicular

backs now bending. You men

who were born barefoot

but earned your shoes.

You men who still look

me straight in the eyes,

even from the Thursday

Obits. You Biblical men

with too many children. You

men who loved women

as much as you beat them.

In “Goodman’s Bay II”, Campbell weaves history, forgotten childhood games, and a popular public park into a fabric that celebrates that most unpopular of Bahamian truths: the deep-deep, long-term, uneasy union between the Bahamas and Haiti. Goodman’s Bay is a seaside park and the last public beach between Nassau and the monoliths of Cable Beach. In a nation whose coast has been universally for sale to the whitest bidder, Goodman’s Bay has resonances that are both consciously felt by the average Bahamian — who exercises, parties, swims, and baptises the next generation of the born-again there — and unacknowledged: for instance, the fact that this preserve for the Bahamian masses is named for an early Haitian immigrant, Jean-Paul Delattre, an emigre from the Haitian revolution:

Come here on a boat

from Haiti back then, back again

To this fact Campbell adds the imagery of moonshine baby, the children’s night-game from the time before electricity, which involved broken glass, shiny pebbles, and baubles, all placed around the outline off the smallest child on a moonlit night so that when the child stood up her image would gleam in the dark. In so doing, he builds a monument for the forgotten.

. . . we jewel the edges of his body

with shattered bottles, then bear him

to the foot of casuarinas in order that his born

silhouette self may freely flash and prance —luminous shadow lifting from the sand

of this beach name after a black man.

I have chosen to celebrate these most Bahamian of Campbell’s poems, but that is not to say this collection is bound by any geographical space. Indeed, it is as global as the twenty-first century itself, with poems that skip across the Caribbean like a stone, leaping with ease from Barbados to Trinidad to Grenada, to more than one Bahamian island. There are poems that speak with the bitter tongue of the exile, and poems on whose edges the imperial North could break. There are poems that are intensely personal, and poems that celebrate love and running and swimming. The range of Campbell’s vision is as vast as the Caribbean itself, and as layered; and he expresses it in a poetry that is tight, robust, and seasoned with all the influences that have shaped the man.

Campbell nods to the formal in “Masquerade”, with its English sonnet sequence. Even here, though, it is not showing off that he is doing, but fitting the form to the subject; in a poem about Barbados, “Little England”, the form — sonnets with loose rhymes and half-spun turns, all fitted into the shape of Crop Over and inscribing the journey of a minor celebrity of Bajan origins — adds complex layers to the content. (As all good poems should do.) But Campbell’s formal forays are not all European. He draws also upon the vocabulary and structure of Rastafari, writing praises and chants and making them work; he presses into service the very African call-and-response of the New World, and creates a fantastic mash-up of Shabba Ranks and Aimé Césaire. It is a virtuoso performance, and worthy of the recognition that this collection has earned.

•

In A Light Song of Light, Kei Miller’s third collection of poems, the subject is writing itself. Or, perhaps more fairly, the subject is that age-old Rastafari, Children-of-Israel contemplation: How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land? For Miller is, by his own admission, a not-so-reluctant exile: “I have decided, against all odds, to stop being an immigrant,” he wrote recently at his blog. And while that blog post may have been written the year after A Light Song of Light was published, the poems in this collection suggest that Miller’s decision to grapple with new issues of belonging had already been taken.

“A light song of light,” Miller says, “is not sung / in the light: what would be the point?” And throughout the twelve movements of this opening psalm, “Twelve Notes for a Light Song of Light”, the act of singing in a strange land is explored. It “swells up . . . in wolf time and knife time . . . it hums / a small tune in daylight, but saves / its full voice for the midnight.” The poem weaves its way through the different possibilities of the song, all the time emphasising the hybrid, the atypical, the unexpected:

A light song of light meditates in the morning,

does yoga once a week, accepts the law

of karma. It may not worship in a synagogue

it may not worship in a balmyard . . .A light song of light is not reggae,

not calypso, not mento or zouk,

not a common song from a common island . . .

Miller’s collection weaves back and forth between worlds, and these worlds are both temporal and geographic. It is divided into two parts, the first called “Day Time” and the second, unsurprisingly, “Night Time”, but it is rarely easy to pinpoint the difference between them. It’s true that the poems in “Night Time” appear to be more unsettling, flirting with the fantastical, casting spells, and presenting mythologies and spirits like Rolling Calf and Coolie Duppy, rewriting creeds and turning obeah back on itself. But that isn’t to say that the poems in “Day Time” are any more settled themselves. Rather, perhaps, they reach for the concrete, they attempt to stand on the scientific. But they rarely achieve those goals. In the short but affecting “Some Definitions for Light (II)”, the attempt at definition (“The lungs of butchered animals are called lights . . .”) only makes the subject more complicated:

I have sometimes wondered … if, before the blade falls, cows and sheep and ducks fill their lungs with the weight of their dying . . . if their final sounds are light calling out to light.

Likewise, obeah makes its own appearance in the daytime, in the poem “In Defence of Obeah”:

was not just cat bones,

parrot beaks, the teeth

of alligators . . .not just a sundown

of candles . . .

……….the slow

backward recital of verses

— but also “an anti-drowning . . . / an anti-breaking . . . / a knowledge / and it was all of that.”

But we can’t be too demanding. It is all the Lord’s song, after all. From the “strange land” with its yoga and not-reggae self, Miller’s collection travels back and forth between the Caribbean and other worlds, between the past and the present, between the humming of the daytime and the night’s full voice. The Singerman, who “beat his tune / out from a sheet of zinc,” is a recurring figure, both in spirit (as in “The Zinc Roof”) and in person (“A Short Biography of the Singerman” and “The Singerman’s Other Job”, among others). He is the only being, it seems, who can straddle both the daytime and the nighttime, bridging all the worlds, even to death. Ultimately, the separation imposed on these poems by the act of publication collapses, rather like the distinction between immigrant and emigrant, between home and abroad, and what remains is a bricolage of fragments which illuminate by their very disparate nature.

I come away from A Light Song of Light with a catalogue of favourites. I am taken by Miller’s urge to define, and to show the impossibility of fixing definitions at the same time; I will return again and again to those poems that tackle the ideas around which he has woven the book. I have a personal fondness for “The Law Concerning Mermaids”, which is both frivolous and subversively political at the same time: “There was once a law concerning mermaids . . . the British Empire was so thorough it had invented a law for everything.” I am also struck by “The Longest Song”, which ends with the image of the condemned man who, given the chance to sing one last song, “begins // ten billion green bottles standing on the wall.” But it is “Noctiphobia”, a maybe-true story about the poet’s grandmother that I first encountered many years ago when writing about my own grandmother on a workshop board in cyberspace, that holds a very special place for me, ending as it does with these powerful lines:

……………………The devilman is dead,

choked on fishbone when he saw my grandmother approach,

baby sucking from her tit. But I only remember her dying

shivering on a cot, singing, Why should I fear

de night or de pestilence which walketh inside it?

Indeed. This comes almost at the conclusion of the book. But though it is a dying, it is not an ending. For the real conclusion, we must return to the beginning to be reminded that “nothing is so substantial as light, and that / light is unstoppable, / and that light is all.” Exile is irrelevant. Everything is everything. And the song has been sung.

•

Ghosts, demigods, and mythological heroes people the poems in Ishion Hutchinson’s Far District. This debut collection explores a familiar (for the Caribbean) tale of exodus and exile. Jamaica, for the poet, is a land of spirits and memories, a place frozen in time, and also a crossroads, a meeting place of the old world and the new, of the living and the dead, the desert and the drowned. To write, to be productive, the narrator must leave, and is only called back by death itself.

Hutchinson’s collection is in some ways a troublesome one. It weighs far more than its slimness might suggest — perhaps too much, some might argue. His subject is a “Far District” — which might be an actual location in Jamaica, or Jamaica itself, or else the fractured identity that the Caribbean creates. The “I” in these poems becomes the archetypal Caribbean writer, the one who must leave his home to find it again, who must choose, at least in the beginning, between career-in-exile and invisibility-at-home, and who is perennially troubled by the decision.

It is perhaps no accident, then, that mythologies — Caribbean, Biblical, African, classical — interweave in this book. It is also perhaps no accident that bodies of water — rivers, oceans, lakes, and seas — mingle and meld. Water, after all, is widely recognised as symbolising the spirit; in a work in which spirits are so central, it is no wonder that water recurs again and again. And indeed the poet tells us, in the beginning of the long title poem, that: “the sea is our genesis and the horizon, exodus.” So at one moment we are in the Caribbean; at others, we skim the Mediterranean; at still others we are witness to the things that float by on rivers. These include drowned Doris, transformed into Ophelia —

Her melody broke through a shell

over the town that August we found

her in the arms of native Ariel,

strands of hair and leaves in her mouth.(“Doris at the River”)

— as well as No-Name-Eusebius of “Penalty Shot”, who “rafted to school” and smelled “of fish / scales and lime,” and who, perhaps because of his watery connection, perhaps because of his namelessness, “could strike the football / like a killer.” Sometimes we are taken to water-pipes to watch a Jamaican Venus wash herself, or even ride the New York subway, a twenty-first-century River Styx. Water rains from above and settles down below in Hutchinson’s poems, and even when it’s expected that we’re far removed from it, water intrudes unexpectedly:

This is how black burns out,

how the glow becomes ash,

and, like everything in this rutted road,

overflows to the harbour,

crossing the ancestral ocean(“The Enigma of Return”)

Far District begins in childhood and carries us among the mountainous countryside of Jamaica, where duppies and ghosts mingle with the failing architects of a federated Caribbean. It transitions, smoothly, almost without calling attention to itself, migrating northward, heading with the poet to New York City, and the images change, the individuals populating the verse growing more cosmopolitan but never less mythological. It returns, closing the circle, back to Jamaica — Jamaica in the nighttime, ghost-haunted, as the poet returns to bury his father.

Hutchinson’s verse leans well towards the classical in structure. Echoes of Walcott are strong in places, particularly in poems such as the many-sectioned title poem. There is a definite intellectualism, almost a coldness, about these poems. One can almost see the poet digesting T.S. Eliot’s over-quoted maxim from his essay on Philip Massinger: “immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different . . . A good poet will usually borrow from authors remote in time, or alien in language, or diverse in interest.”

Hutchison, it seems, follows this observation to the letter. His book is not only rife with allusion; it also comes (like The Waste Land) equipped with its own set of notes. It is a quality that stands between the reader and the way in to the poems. The allusions are almost self-consciously literary. Adam and Vulcan, Charon and Prometheus appear in diverse places, together with intellectuals and artists from around the world: McKay, Defoe, Eliot, Shakespeare, and others. These greybeards stand alongside the old higues and the duppies of the Jamaican hillsides; they haunt the riverways and choke the gullies, but they are not the only phantoms lingering in this book. Spirits of popular culture gather here also: Clint Eastwood and Jimmy Cliff and Peter Tosh, and they mingle with nation-heroes Nanny and Cudjoe as well as more personal familiars: Aunt May, Mister Bell, drowned Doris, and the unforgettable Gabby, drowned son of the mango-tree owner of the poem “Two Trees”.

Often Caribbean poets are selective, choosing one strand of our cultural richesse to pursue over another. It is as though in Far District Hutchinson has determined to honour all the ancestors, no matter who they may be. Some readers will have an issue with this; what have Cavafy or Montale to do with our affairs? This is worth considering. However, if the Caribbean is indeed, as many have suggested, the meeting place of the worlds and the cradle of what we now know as globalisation, then it is entirely likely that no artist, no culture, is entirely irrelevant to us. Hutchinson appears to have reached this conclusion already.

In all, Hutchinson’s collection is like a too-rich meal, difficult to swallow in one sitting, but worth savouring anyway. It is tempting to suggest there is just too much in it for one book. But to do so would be to overlook the central truth that every element which finds its way into this collection has a place there. Not only is it a part of this poet’s experience, but it is also authentically part of the Caribbean experience as well. Far District may not be the first book one might take from one’s shelf to read, but it will without doubt be one of the most rewarding.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, September 2011

Nicolette Bethel is a Bahamian playwright, poet, anthropologist, and blogger, and the editor-in-chief of the online literary journal tongues of the ocean. Her work has been published in a variety of print and online publications, including The Caribbean Writer. She was formerly director of culture for the Bahamas, and is now assistant professor of sociology at the College of the Bahamas, and the founding director of the annual Shakespeare in Paradise theatre festival.