What she said

By Kelly Baker Josephs

Conversations with Paule Marshall, ed. James C. Hall and Heather Hathaway

(University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 978-1-60473-743-1, 240 pp)

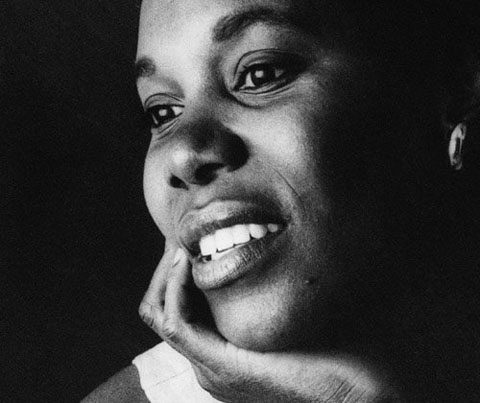

The younger Paule Marshall. Photograph courtesy the University Press of Mississippi

Although she has won several prestigious awards, including a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship (the “Genius Award”), a Gugghenheim Fellowship, and grants from the Ford Foundation and the US National Endowment for the Arts, Paule Marshall is a relatively unsung word warrior. This new collection of interviews with the Barbadian-American writer, part of the “Literary Conversations” Series from the University Press of Mississippi, signals some recognition of Marshall as a major figure worthy of study across time.

In Conversations With Paule Marshall, editors James C. Hall and Heather Hathaway have provided a truly necessary resource for anyone interested in Marshall’s work and her growth and development as a writer in the more than five decades since the publication of her first novel, the semi-autobiographical coming-of-age story Brown Girl, Brownstones (1959). There is a handful of other book-length studies of Marshall’s writing, and a few more on her work alongside one or two other major writers (for example, co-editor Hathaway published Caribbean Waves: Relocating Claude McKay and Paule Marshall in 1999), but this volume presents Marshall primarily in her own words. Interviews, however, can be a problematic resource. I am always ambivalent about how much weight to put on a writer’s words and life story. I greedily consume details about a writer’s travels or participation in writing “circles,” because these somehow seem like objective influences on his or her work, but I am hesitant to read too much into information about health, habits, or even family life, because my primary focus is always the art rather than the artist. I am wary of biography; how much of it can I use to understand a writer’s work?

Because “the work” (as Marshall sometimes refers to her body of writing in later interviews) is my focus, my review speaks from this place of academic interest in Marshall. But, of course, there are other reasons for reading such a collection. Although not quite as beautifully phrased as the prose she often laboriously struggles over before publishing, Marshall’s ideas in these interviews are intriguing, and the longer interviews tease out their complexities. I do not imagine the collection will be of interest to anyone who has not read any of Marshall’s work, but readers familiar with one or two of her novels will find much worthy of reading here — particularly Marshall’s accounts of her growth as a writer.

For example, there is the story of her experience with her first book contract, which she recounts in a 1984 interview with Sally Lodge for Publisher’s Weekly. Marshall, thrilled with her first contract for Brown Girl, Brownstones, and “thinking that the world had said ‘yes,’ and that maybe I did have something going for me,” has a chance meeting with Bennett Cerf, co-founder of Random House. He tells her, “Well, you know, nothing usually happens with this kind of book.” In a scene that mirrors the climax of Brown Girl, Brownstones, Marshall was plunged from the exhilaration of her emergent success to the devastation of marginalisation. With his offhand and possibly kindly meant words, Cerf indicates to Marshall that “even though my book was going to be published and the publisher found some literary merit in it, I was not really a part of the literary community.”

And Cerf’s prediction was self-fulfilling. Marshall’s first novel, while critically well received, was not successful on any financial scale. Tellingly, this collection of interviews starts with pieces dated after the publication of her second novel, The Chosen Place, The Timeless People (1969). The first interview is really a conversation, a lengthy edited transcription of Marshall’s visit to Hiram Hadyn’s class at the University of Pennsylvania in 1970. Hadyn was Marshall’s editor at Random House, which perhaps explains the hint of condescension towards her throughout the conversation. Given my own near-adoration of Marshall’s work, this was for me a disconcerting way to begin the collection, but the editors arranged the interviews chronologically, and this particular conversation with Haydn’s class is one of the collection’s highlights because it was previously unpublished (and only “available” via the special collections archive at the Stanford University Libraries). Still, there are gems in the conversation for those interested in Marshall’s development as a writer: in particular, the freshness of The Chosen Place, The Timeless People for Marshall at that time, and her tacit conclusion that its publication solidified her reputation as a writer, add much to our understanding of the place of the novel in the arc of her career.

The collection is uneven, but usefully so. There are interviews that mirror direct transcription, with the standard arrangement of names or initials to indicate speakers and reflect a dialogue. Then there are those that are formatted as essays, with heavy quoting of Marshall’s words from the “hidden” interview. Some pieces are overly academic in tone, and others are more casual and quite intimate, written for general interest publications like Essence. Some are extended interviews; others are so short as to make the reader wonder at their inclusion. Thus, as a whole, the collection provides not only different facets of Marshall herself, but also of her readers, critics, and general intended audience.

Most interesting is the book’s other previously unpublished piece, a lengthy conversation with Hall and Hathaway from 2001 which, although it is the penultimate piece in the collection, serves as a mirror bookend for the Haydn class conversation. This is a much more refreshing piece than the opening interview. It is clear that Hall and Hathaway have spent enormous amounts of time and energy with Marshall’s work (Hall going even as far back as her writings when she was a reporter for the magazine Our World, in the mid 1950s), and are therefore more able — and willing — to coax interesting and useful information from her.

Of course, the interview is also better because by this point Marshall herself is more mature and sure of herself as a writer, as an established artist. And between Haydn’s interview in 1970 and Hall and Hathaway’s in 2001, readers can trace Marshall’s development throughout the collection. I am not sure why the editors included the book’s final interview, which falls after their own piece. Yes, it is conducted much later, in 2009, and covers Marshall’s latest book, Triangular Road (2009), thereby making it possible to say the entire volume covers four decades of interviews; but it is fairly short, seems an afterthought, and is a bit of a letdown after the careful consideration of Marshall’s work in the previous piece. This, again, is one of the disadvantages of the chronological approach of the collection. But as the volume traces Marshall’s life and life’s work, there seems no other appropriate organisation.

There are no large, headline-worthy revelations in Conversations with Paule Marshall. Like Marshall’s work itself, the interviews build on each other to create a picture of a steady wordsmith, one who is meticulous about her craft and dedicated to certain themes. Whenever one sits down to a collection of interviews with an artist (as I am sure can be seen in the other collections in the “Literary Conversation” series) there are bound to be repetitions and contradictions. With Marshall, there are fewer of the latter, but several of the former. However, such repetitions, rather than distracting, are strangely gratifying. They reinforce for readers that all her writings are deliberately connected; that even as she experiments with different perspectives, approaches, methods, and directions, in the twenty-first century Marshall is still meticulously exploring the issues of community and culture, roots and reconciliation that she so carefully represents in Brown Girl, Brownstones.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, November 2011

Kelly Baker Josephs is an assistant professor of English at York College, City University of New York, managing editor of Small Axe, and editor of sx salon.