A fine balance

Nicholas Laughlin looks back at the 2012 exhibition Into the Mix, and considers the feats of balance required of artists crossing the tightrope of a geographical horizon

Still from Temporary Horizon (video, 2010), by Heino Schmid

Into the Mix, an exhibition curated by Aldy Milliken, ran at the Kentucky Museum of Art and Craft (KMAC) in Louisville from 4 February to 14 April, 2012. It featured works by ten artists: Janine Antoni, Christopher Cozier, Blue Curry, Carlos Gámez de Francisco, Marlon Griffith, Sofia Maldonado, Wendy Nanan, Ebony G. Patterson, Sheena Rose, and Heino Schmid. The following notes reflect on some questions raised by the show — and by other survey exhibitions that use geography as a theme or organising principle.

•

In his video work Temporary Horizon, Heino Schmid documents his attempt to balance two glass bottles atop each other at an unlikely angle — a playful feat of steady-handedness. After several attempts he succeeds, then Schmid moves out of the frame, leaving his precarious temporary sculpture behind. Within seconds, the bottles fall, with a decisive clink. The video loops back to its beginning, and the process resumes.

Janine Antoni’s Touch documents a different kind of balancing act. The artist strung a tightrope along a stretch of beach outside her childhood home in Freeport, and made a video recording of herself traversing her own “temporary horizon.” The title of the work derives from a clever calculation of camera angle and rope position: as Antoni edges forward, the weight of her body makes the tightrope dip and appear to touch the sea-sky horizon in the far distance.

The visual simplicity of both artists’ actions — balancing two bottles, walking a tightrope — belies their efforts at preparation. (Antoni has spoken about practicing on a tightrope in her studio for weeks, and Schmid’s little trick of equilibrium required careful study of the bottles’ geometry and weight.) The viewer’s likely first reaction is plain admiration for the artists’ agility. But both works also function — almost too readily — as metaphors for the conceptual, formal, material, and indeed personal negotiations involved in any act of art-making.

Art is always a high-wire act, with no safety net. The artist must find a point of equilibrium between ideas and materials, ambitions and limits, creative autonomy and the expectations of audiences, private intentions and public communication. And, as Touch makes obvious, balance is a process, not a state. It means holding steady a centre of gravity: a negotiation among mass and momentum and energy. On this depends stability and mobility. The tightrope walker keeps moving, or else she falls, and her successful journey is an ongoing compromise between her own mass, tension in the wire, and universal gravity.

•

Feats of balance — negotiations among competing forces — recur in the works of all ten artists included in Into the Mix.

Marlon Griffith’s suspended paper sculptures, destined to be discarded, bargain between the idea of the permanence of art and the ephemerality of his medium. Sheena Rose’s animations seesaw between Bridgetown, Barbados, and Cape Town, South Africa — and between the tactile qualities of her individual drawings and the digital sequences they ultimately compose. Ebony G. Patterson’s tapestry installation Gully Godz in Conversation sets up an uneasy tension between received ideas about femininity and masculinity, between a painterly approach to composition and the rude eruption of her images from the pristine walls and onto the gallery floor. Blue Curry’s sculptures — assembled from objects often found in street markets and junk shops — and Christopher Cozier’s Little Gestures — a series of small printed objects made using ordinary office supplies like cardboard, rubber stamps, and binder clips — ask the viewer to juggle notions of what are the appropriate materials for art. And each Baby Krishna in Wendy Nanan’s series of papier-mâché sculptures holds a symbolic object in either hand, as if weighing one against the other: sugar versus salt; food (individual sustenance) versus oil (industrial export); human blood versus the Sanskrit Om, the sound of divine consciousness.

•

Still from Touch (video, 2002), by Janine Antoni

I started to notice that it wasn’t that I was getting more balanced, but that I was getting more comfortable with being out of balance …

I wish I could do that in my life.

— Janine Antoni, Art21 interview, 2003

•

Where is the “temporary horizon” in Heino Schmid’s video? Is it the plane or the edge of the surface on which he balances his bottles? The edge of the video frame, which conceals further information about the room where the performance happens? Or the almost inconsequential swish of water, merely a few drops, inside each bottle — creating a miniature horizon line barely visible to the viewer, a microcosm of a physical geography dominated by sea?

•

… you can start then,

to know how the vise

of horizon tightens

the throat …

— Derek Walcott, Another Life

•

A horizon is a line that divides. Not just sea from sky, as we stand on shore looking outwards; it divides what we see and know from what we don’t. It is the limit of vision, and a provocation to go further, to imagine past the limits of experience.

A horizon is a boundary, but one that is never fixed. It moves as the observer approaches. It is a permanent invitation, or challenge. Or a permanent question: where is here?

•

If the artists of Into the Mix are all stepping along metaphorical tightropes, they are also — like Antoni in her video — stepping across horizons. It is a fact of biography that all ten were born in a common geographical region. Unsurprisingly, their work often investigates a vocabulary of images and concepts derived from the social circumstances of that geography. But just as often, these artists are preoccupied with personal questions and histories. The paths of their curiosity are not bounded by (or bonded to) location.

Neither are the artists themselves, as the stamps and visas in their passports easily prove. Antoni and Curry, born in the Bahamas, now live, respectively, in New York and London. Griffith, born in Trinidad, lives in Japan. Patterson, born in Jamaica, and Carlos Gamez de Francisco, born in Cuba, both now live in Kentucky. Sofia Maldonado, born in Puerto Rico, divides her time between San Juan and New York. Like the others, Cozier, Nanan, Rose, and Schmid all make and show their work in multiple international locations, through the instigation of increasingly global art networks made up of galleries, residency programmes, and other art institutions.

Of course, even in this “elastic geography,” as Cozier describes it, location still matters — but not always in the old or expected ways. What useful geographical labels can we apply to an exhibition of artists who live in Asia, Europe, and the Americas, hosted by a museum in Louisville? In an email exchange soon after the opening of Into the Mix, KMAC curator Aldy Milliken joked that the show could have been called “Made in Kentucky.” That title would be at least half true. Gamez de Francisco’s studio is in Louisville, Patterson’s in Lexington. Griffith made his paper installation on site at KMAC. Some constituent objects in Cozier’s Little Gestures were also made in the museum, using materials specified by the artist and sourced locally (others came from previous versions of the work made in Johannesburg and Hanover, New Hampshire). Maldonado painted directly onto the façade of KMAC, assisted by Louisville volunteers and observed by passersby.

But Into the Mix was also at least partly “made” in Stockholm, Milliken’s former institutional base, where he began his preparatory research; and in Miami, where his encounter with a Nassau-based curator during 2011’s Art Basel Miami Beach pointed Milliken towards several of the artists he later invited to participate. You could also argue that, in a practical sense, Into the Mix was “made” online, through the series of email and Skype conversations between curator and artists and advisors which arrived at a conceptual shape and logistical arrangements. And experientially the show was “made” in the imaginative space where all its participants met and engaged with the others’ ideas and interests.

So place of origin is, at best, an inadequate means of defining a show like Into the Mix. But these ten artists all do have actual places of origin, which appear in their biographical notes and determine the kinds of passports they carry. And critical scrutiny — whether from individuals or institutions — is a form of border control, complete with preconceptions and prejudgements. What do these artists “declare”? What are their strategies as they move between horizons, trespass across borders?

•

Untitled (slide projector carousel, ashtray, decorative plant holder, 2011), by Blue Curry

If the border guards tend to believe that certain subjects — say, “identity,” “ethnicity,” “resistance” — are more or less appropriate for artists from particular geographical backgrounds, the corollary may be that certain media are more or less appropriate for particular subjects.

Ebony Patterson’s intense exploration of materials is an apt rejoinder. Her elaborate and heavily embellished tableaux are constructed from layers of textiles, paper, sequins, rhinestones, and artificial flowers — cheap, kitsch materials which she enlists in her investigation of self-transformation and self-esteem. Her Gully Godz are imagined versions of young men from Kingston neighbourhoods usually associated with brutal violence and poverty. Their heavily made-up faces and androgynous, floral-patterned outfits exaggerate the visual style of dancehall culture — an assertion of presence and personal validity in response to Jamaica’s restrictive class hierarchy, which, through the intervention of mass media, has crossed over into an international urban trend. They are at once “pretty” and sinister, and they are the last subjects we’d expect to see depicted in woven tapestries, with all the associations of that medium. So where else are they crossing over?

The viewer might assume that Cloud, Marlon Griffith’s installation of paper sculptures, is another kind of crossover: the Trinidadian artist’s adoption of the traditional paper-cutting techniques — mon-kiri — of his current home, Japan. But these objects, which the viewer eventually realises are wearable masks, also draw on the fabrication techniques of Trinidad’s mas camps, where costumes — often wearable sculptures — are designed and built for the annual Carnival masquerade. The paper sculptures are also a direct response to an early phase of Griffith’s career, when from financial necessity he used inexpensive brown paper and cardboard to make drawings — against the advice of commerce-minded collectors, who argued that works made from these materials could not endure, had no lasting worth. As Griffith explains, this triggered his longstanding fascination with the question of how and why audiences perceive value in a work of art. “What do you see in this object?” he asks. Can we look past the utilitarian materials — paper, board, metal rivets — to grasp the intricacy of the artist’s handiwork and a simple delight at the delicate mutability of the images he conjures up: now a flower, now a bird, now a human form, now geometrical abstraction?

Blue Curry’s sculptures are also enactments of metamorphosis: his found and scavenged objects become other objects, or are paused in the process of becoming. He assembles household items, discarded industrial components, odd curios, and natural artifacts into composite entities that ask witty questions about line, volume, and texture. At the same time, these sculptures are weirdly creepy, or perhaps uncanny, in the Freudian sense: simultaneously familiar (as the viewer immediately recognises mundane objects like glass ashtrays, a golf ball, plastic fly-swatters) and strange. Curry’s Untitleds at once resemble chunks of detritus, exotic totems, and specimens of organic-inorganic mutation. They remind us that human beings have a hard time leaving well enough alone: we are obsessed with turning things into others things. For better and for worse, this impulse drives art and capitalism alike, and is implicated in the past and present transformation of landscapes by industrial exploitation, colonisation, and war.

•

Detail of Baby Krishna, “Fauna and Flora” (papier-mâché, oil, enamel, gold leaf, 2011), by Wendy Nanan

But it is a mistake to underestimate the sheer mischief of Curry’s sculptures, or forget that a visual joke can still have a serious punchline. Wit is another mode of imaginative trespass, and a prankish current also runs through the work of these artists.

Sofia Maldonado’s graffiti paintings, for instance, use the visual language and familiar conventions of street art — shorthand for cool global urban youth culture — but often give them a sly feminist twist. Maldonado’s “ultra feminine super heroines with Rapunzel-like tresses,” as the writer Marisol Nieves describes them, raised ire and provoked debate when she included them in a commissioned mural in New York’s Times Square in 2010. Critics accused her of poking fun at Afro-Latino women, portraying them with stereotypical skimpy outfits, outrageous hairdos, and gaudy decorated fingernails. But for Maldonado, the mural introduced “a female aesthetic that is not usually represented in media or fashion advertising in Times Square … These women are strong single mothers or wives who enjoy life and have overcome tough experiences.” It is a cunning riposte, asking the viewer to take responsibility for the negative associations of ethnic and gender stereotypes.

At first glance, Wendy Nanan’s Baby Krishna series projects a kind of melancholy whimsy. Her four depictions of the Hindu deity in infancy — complete with blue skin and topknot — have downcast eyes and cherubic wings. You can imagine them cheekily perched atop a cross-cultural Christmas tree, or sporting with Cupid’s bow and arrows. A viewer unversed in Hindu tradition might wonder about an element of mockery, but for millennia devotees have worshipped a version of the god as a divine child, Balakrishna, and Hindu scriptures often portray him as a practical joker. Nanan’s Krishna, though, is not projected from some mythical antiquity. He apparently is a native of Trinidad, with a heart-shaped tattoo on his bicep to prove his patriotism, and he seems puzzled in his contemplation of the choices facing a small twenty-first-century nation-state. For one kind of audience, he might signify the cultural mashups that increasingly germinate in our contemporary global space — where Hindu deities turn up on t-shirts worn by hip metropolitans, and Bollywood tropes invade Western cinema. For another audience, closer to Nanan’s home, these mischievous Baby Krishnas make a more pointed claim of belonging in a contested multi-ethnic society.

Heino Schmid’s Temporary Horizon also discloses an inside joke. His bottle act was inspired by the antics of a street hustler he observed outside a popular watering-hole in Port of Spain. The rumshop bottle-balancer makes clever use of an unconventional skill to entertain a well-heeled crowd of drinkers and earn a few dollars. Schmid prods us to recognise that the art world is full of smart performers playing similar tricks. Knowing the context in which Temporary Horizon was first shown, at the 2010 Liverpool Biennial, sharpens the edge of the observation. Does the unceasing worldwide proliferation of biennials and art fairs — few countries are untouched — amount to a circuit of playgrounds for rich patrons and favoured entertainers, smoke and mirrors, fast talk, and shell games?

•

Detail of Little Gestures (installation, 2011), by Christopher Cozier

At the same time, there is an equally provocative inscrutability to a work like Temporary Horizon. In the end, why does Schmid try to balance these two beer bottles? Why does Antoni walk her tightrope? Why does Curry collect and pile up pieces of junk? The most basic and perhaps truest answer is simply: because they want to. Something about these acts of imagining and making fascinates them.

The artwork is not entirely complete — has not done its whole job — until it finds its attentive audience, enlists them too in the acts of imagination and fascination. But we should not be over-hasty in trying to understand or interpret. Turning the experience of the artwork into narrative, as we necessarily do when we speak or write about it, also imposes a limit. The viewer must also find a balance between prior knowledge and expectations, and the surprise and mystery the artist offers. As Christopher Cozier says, “The work doesn’t want to be read, in certain ways. It wants to tell a story, but it doesn’t want to tell that story.”

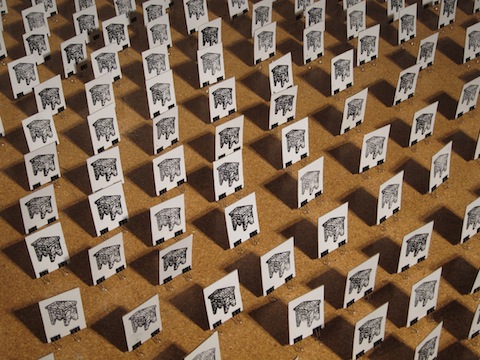

Insisting on that space for the inscrutable is one more way for these artists — and their audiences — to breach bounding horizons. Take Cozier’s Little Gestures. Hundreds of small cards are arranged on the gallery floor in a pattern that suggests the marching ranks of a parade, or maybe a patch of terrain, roughly quadrilateral. Each card is stamped with an icon that may at first seem unreadable: a small table or bench patterned with an antiquated map. The cards are held upright by pairs of binder clips. (Visitors were invited to make and take away their own version of the bench using die-cut, foldable cardboard sheets — a collaboration between Cozier and Trinidadian designer Marlon Darbeau — stacked on a nearby pedestal.)

You could infer that Little Gestures is “about” history, geography, ancestry, domesticity, the bureaucratic processes by which the world is administered, or social conformity. Any of these interpretations might be enriched by knowledge of Cozier’s background, the place where he lives and works, and his wider oeuvre, in which both the bench — known as a peera in Trinidad — and the map are recurring images. It might be useful to know an earlier version of this installation was made in South Africa, or about the artist’s previous floor installations, or his frequent technique of repetition.

But even before you rifle through this baggage of context, Little Gestures — with the modesty of its title — makes a quiet sensory assertion. Look how it occupies and defines a physical space, how the spotlit cards seem to gleam but also cast shadows of varying lengths, how their position and arrangement forces you to slow down, encourages you to walk around them. Liking or understanding are secondary to a basic curiosity: who made this mark, and why?

•

And in that moment of first encounter, knowing where the artist came from or how seems less important than what he or she did here.

•

Postscript:

I may make it a personal mission not to utter the words Caribbean, West Indian, Antilles, Island, Centre/Periphery, Anglophone, Atlantic or Coastal … just to see how we can have a real discussion about the work.

— Art historian Courtney J. Martin, from

an exchange of emails ahead of two artists’

talks at KMAC, 13 and 14 April, 2012

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, November 2013

Nicholas Laughlin is the editor of The Caribbean Review of Books.