The spirits approve

By Ishion Hutchinson

Black Sand: New and Selected Poems, by Edward Baugh

(Peepal Tree Press, ISBN 9781845232108, 134 pp)

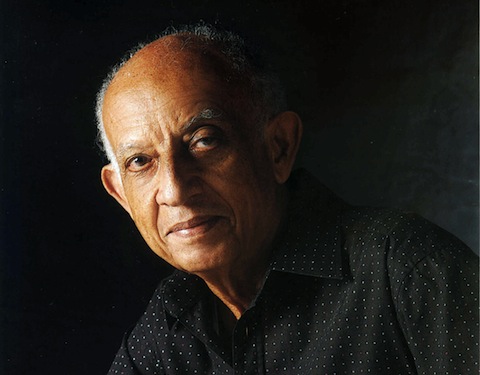

Edward Baugh. Image courtesy Peepal Tree Press

The first aim of speech is to be understood. It is an aim mastered by Edward Baugh in his many celebrated addresses as public orator of the University of the West Indies Mona campus; it is also a chief cornerstone, in different degree, of his prose and poetry. In his prose, the intelligence shapes and dissects with full faith in a scholar’s objective distance. The mastery in Baugh’s poetry, on the other hand, is a closed-circuit seeking of — and towards — what George Herbert called the “soul’s blood” speaking.

Baugh’s immense poetic achievement, indeed, is the fluid way in which he moves beyond expression into comprehension, articulating with superb intimacy those echolocations outside of the verbal framework:

as you read, your fingers tapping the beat,

tapping her river-source of pain and release,

and I’m hearing the beat now as a chattel-house woman,

making tough ends meet, hammers an iron

spike into the ground in the open lot

outside of my bedroom window …(“Soundings”)

In this poem, the primacy and privacy of touch (“the beat”) is stirringly transformed into words; the words wholly embody a life, the chattel-house woman’s, and not as a passive aesthetic objective; she is the motive force between the old and the new worlds. She “pounds / her presence,” the poem ends, “into tough earth, connection / of spirits across oceans, across deserts, grounds / of resistance, resilience. The spirits approve.” It is all the more appropriate that “Soundings” is dedicated to Kamau Braithwaite, who once wrote, “I / must be given words to shape my name to the syllables of trees.” Baugh’s words prove their iron mettle. The spirits approve.

Words are fixed by tone, and tone constitutes the poet. It is through Philip Larkin as a tonal model that Baugh’s voice comes plainly to the ears like, as one poem puts it, “whispering thunder / out of the blue.” Larkin is not overly venerated, however; in “Cold Comfort”, for instance, one of Baugh’s early poems, the speaker feels “authentic shivers” from reading Larkin’s “Aubade”, but nevertheless sucks his teeth at its (Larkin’s phrase) “arid interrogation.” Still, Baugh’s voice — ironic, translucent — grows out of that “sun-comprehending” light apotheosised by Larkin. Baugh’s voice does not proclaim from the proscenium arch, but is uttered intimately from the midst of the stalls, privately bemused at the colloquial register modulating the formal pitch, whetting the language’s two sides to cut deeper:

I’d smile to myself, amused

when some cocksure wanna-be

called up …(“Nearly”)

Here, the reflexive pronoun structure, grammatically not necessary, widens the smile to a sneer, and then the simple and brilliant move to place “amused” immediately after the caesura intensifies the reflexivity of this self-amusement, reducing it to something nearly cynical. (The cynicism in this poem intensifies to a lovely dyspeptic candour when read next to another early poem titled “The Poet Bemused”.) Later, the poem repeats the phrase almost exactly, only now the speaker is “amazed,” and that advancement of emotion, risky and honest, is the exact state, one imagines, which the muse (encoded in “amused”) creates after its descent into the poet. The epiphany the poet here comes to is this:

……..Today I smiled

to myself, amused, amazed

to realise that after two

slim volumes and nearly

fifty years, I’d nearly

reached my hundred.

Perhaps better than “epiphany” is the poet’s word, “realise,” as he merely comprehends along a rational, commonsensical radius a detail for which the evidence is the current volume of poems itself. It is true that it is nearly fifty years since Baugh’s brand of poetry has given the quotidian Caribbean experience, and often the unexamined Caribbean life, an exhilarating poetic presence. It is a model for which Larkin, in the last century and in his own world, is the supreme case. Technically, though, Baugh is somewhat ahead of Larkin in this restraint, since he has only published one single entirely new volume of poetry — his first, Tales From the Rainforest (1988). His subsequent collection, It Was the Singing (2000) — like Black Sand — includes poems from previous books. To read back and forth over the years is to encounter poems that, in a phrase from Hardy, “ravish the sensuous mind” — any mind, really. But finally we settle into the new to see how they endure next to the old.

•

The first impression is that a number of Baugh’s new poems seek to complicate old territory: Caribbean landscape and characters, travel and history, memory and language, aging and poetry — and it is this last subject that the greater portion of the new poems are most committed to exploring. Black Sand opens unexpectedly with a kind of epigrammatic invocation that works well to tune the ground for the others to follow:

and when that daring song-tower falls,

may goat and children know delight

poking round each rubbled height

and sunlight

strike bright music

from shards of weed-grown walls.(“End Poem”)

The antithesis of rise and fall is made simultaneous, as if you are instanced into inferno and paradiso via the lyric’s power to transgress time and space. The poem’s magnificence is in its prismatic soundscape, rhymes within rhymes, but the starring quality is of those successive “ight” sounds ticking out a kinesthetic music. This lyric acuity masks the apocalyptic scene of the poem, and helps to elevate the redemptive counter of “strike bright music” — which, as a line by itself, brings to the ear Paulina’s imperative in A Winter’s Tale, “music, awake her; strike,” reanimating Hermione’s statue.

Whereas “End Poem” hones a crystalline pressure that enacts the redemptive energy of sunlight and music, something similar mutates in the title poem of the collection, “Black Sand,” only this time with an elastic, eddying style. Due to its rhetorical conceit, modelled on Rudyard Kipling’s “If—”, the insistence feels a little overwrought:

If the poem could open itself out and be wide

as this beach of black sand, could absorb

like black sand the sun’s heat, and respond

to bright sunlight with refractions of tone,

nuances that glamour would miss, if this

could happen, if the poem could yield …(“Black Sand”)

The accumulation is straitjacketed by the structure of the conditional clause followed by a simile that isn’t very surprising; similarly, the scope is too neatly circular — sun in the beginning, moon “lifting over the sea” at the end — making the overall effect too familiar. It is not so much that the poet loses what Kipling calls “the common touch,” but rather that, in some moments, he has grasped it too intently.

In other poem-as-subject poems, like “What’s Poetry For?”, “To the Editor Who Asked Me to Send Him Some of My Black Poems,” “The Comings and Goings of Poems,” and the luminous “Slight and Ornamental,” Baugh’s lucid and ludic gift is at its optimum. Take this description of a butterfly in flight from “Slight and Ornamental”: “How it made light of gravity, displaced / such weight of air! Space expanded / to its map of detours and digressions.” The depiction is so focused and crepuscular, the insect is a virtual iconography in the air. Two lines later, the butterfly is given wonderful Marvellian touches when it “eavesdrop[s] on the conversation of trees / and the ruminations of street-dogs filing / single-mindedly down the sidewalk.” Similarly, in “The Comings and Goings of Poems,” Baugh’s attention to the familiar can result in exquisitely fine narrative compression that works singingly:

in a delicatessen in Silver Spring, Maryland,

manoeuvring the spare ribs and chicken mushroom

with a plastic fork, and sucking a strawberry

smoothie through a plastic straw, comfortable

vacant and anonymous in the goings and comings …

This kind of compression is absent, or turns glib, in poems like “The Limitation of Poetry”, which reads in full: “It was a poem / that brought them together; / now no poem / can heal the hurt.” Nothing is at stake here in language, harrowing as the sentiment may be. The ending of the quiet but tough-hitting “To the Editor Who asked Me to Send Him Some of My Black Poems,” however, earns its circumspection, particularly in the way the end rhymes quicken the pulse of the familiar threat, so that this could stand as a poem on its own:

not wishing to put you

and your safety on the line

I beg, respectfully, to decline.

•

In his further poems’ leap from baldly taking poetry as their subject, Baugh’s poetic comprehension surges with near unparalleled force. His observational eye — an eye that is sociological, alert as ever to the contrasts of the world around him — records reality with precision. “The Ice-Cream Man,” for example, is a miniature distillation of Jamaica’s class divide, economic predicament, and rapidly growing xenophobia and insularity, all from the perspective (as opposed to the point of view) of an ice cream van tinkling through a neighbourhood:

…….. although no deer

or antelope play in this neck of the upscale

concrete woods. He must have lost

his way, gliding like the graceful white

swan out of bygone dream time, where

children frolicking on well-kept lawn

rushed out at the sound of his sweet approach.

You can’t even see the lawns or gardens

now, only the high, burglar-daunting

walls.

The portrait is grim, but it is not quite — to revise Larkin — “Jamaica gone,” because “the ice-cream man has done / his market research well. His clientele? / The security guards at the gates of the gated / communities which give the avenue its class.” The vision may be warped, but it shows the terrific Jamaican spirit for survival, and does well to solidify the homily that ends the poem: “a sweet tooth / is no respecter of persons.”

“Amadou’s Mother,” which begins, “Bring me your hungry and your poor / and I will have them gunned down / in their doorways in Brooklyn and the Bronx,” is another poem which strikes what Walcott has called the “sociological contours” of postcolonial society. The lines just quoted are, of course, spoken by the Statue of Liberty, and they are a vicious recasting of the famous lines from Emma Lazarus’s sonnet “The New Colossus”. When Amadou’s mother comes to speak in the second part of the poem, her voice is heartbreaking, the pathos piercing, especially in light of the recent Travyon Martin case. Here is how she closes her monologue:

…….. They have made a desert of my heart.

Nobody wanted to know who Amadou really was.

Only when the person comes and says the truth

will forgiveness come. He was my son.

He was only a boy going home.

Baugh’s passionate alertness to the contemporary imbalance of society, to the danger in not wanting to know, which ends in an unforgiving silence, is baselined by the keen historical awareness that poems like “Monumental Man” and “A Nineteenth-Century Portrait” show. Baugh speaks composedly against the silence; he unveils the historical horror via chiaroscuro and irony:

…….. How well the boy’s

dark visage serves design,

matching the dark of the trees to cast

in relief the pale, proprietorial white.

Those were the good days; they didn’t last.(“A Nineteenth-Century Portrait”)

Or in “Monumental Man,” a poem about George Washington’s statue and his

his terrible teeth, which he replaced

with dentures made of ivory and

teeth pulled from the mouths of his slaves.What startles most, most reassures

is that I can still be discommoded.

I see him, saddle-smart, erect,

I see him flash an ivory smile,

superior man, superior teeth.

At his death he willed that his slaves be freed.

Baugh’s final line is remarkable for its lack of contempt; a more hysterical poet would have ended at the penultimate line, amputating a fidelity. Bitter as it is, it is part of the whole truth necessary for forgiveness to come.

Black Sand raises the latitude of Baugh’s place not only in Caribbean poetry but in the whole of English poetry. One is truly blessed to enter the beneficence of his house of poems. The great delight is to hear and remember the melody of his voice, a voice that is pitched just above actual speech. Baugh has patiently created an important oeuvre that is indelible. Unforgettable too is his humility — a seismographic lack in some younger Caribbean poets — that apprehends the great, most terrible human truth that when he “leave[s] this place / guinea-hen weed will take over, for good.” But he will have left also, in the words of Milton, “a good book [which holds] the precious life-blood of a master-spirit, embalmed and treasured-up on purpose to a life beyond life.”

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, November 2013

Ishion Hutchinson is a Jamaican writer, and assistant professor in the department of English at Cornell University. His first book of poems, Far District (2010), won the PEN/Joyce Osterweil Award and the Academy of American Poets’ Larry Levis Prize, and he recently received a 2013 Whiting Writers’ Award.