Flood

Fiction by Barbara Jenkins: an excerpt from a novel-in-progress, De Rightest Place

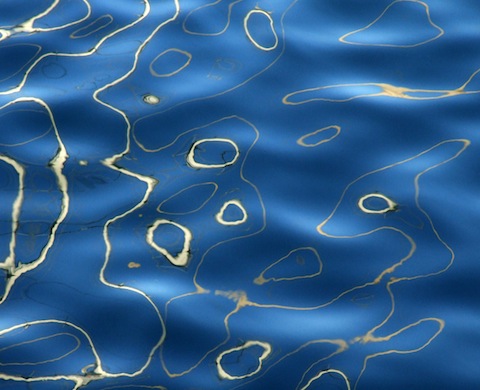

Image posted at Flickr by Vicente Moreno under a Creative Commons license

And outside, in the awake world, the dry season sudden cloudburst explodes, scattering shrapnel raindrops, that pierce through leafless trees, that pit the dry caked laterite, hurling loose dirt into the air from a million tiny craters, joining to form a web of cocoa-brown runnels that unite and split, rushing onwards carrying mud, dead leaves, and parched grass, styrofoam cups, FCK boxes and New Waters plastic water bottles, rivulets racing towards drains already full and swiftly clogged, that burst through into the streets, surging and roaring, ripping off sheets of asphalt, dense grey-black rafts buffeted on churning, raging road rivers.

People who going about their Glorious Saturday business before midnight mass race for shelter beneath the overhanging eaves of shops and, from behind screens of water pouring off the roof, they watch the scene of devastation flowing past, even as the overflowing drain climbs over the curb onto the pavement, over shoes and ankles until, as one, they pound on the siesta-shut doors of De Rightest Place and the banging below smashes into Indira’s dream. Her eyelids flip open and, still in a sleepy stupor, she stumbles down. Who is it, who is it? Wait. Wait a minute. I’m coming. And she open the doors for them, the drenched, to come flooding in, and she puts on the kettle and an extra large saucepan to brew coffee and tea and cocoa to warm up her half-drowned impromptu guests.

Among the washed-up flotsam Indira sees a boy, a young man, tall, his mother’s milk scarcely dried on his face, whom she remembers spotting from behind her secret shutters during the week-long painting of the building’s façade, the one whom she’d looked for every day, she still can’t figure out why, but she remembers the unexpected tremor in her groin, and the urge she felt to stroke and cuddle and caress his innocence, and this boy, this young man, is here and he seems to take charge, running up and down the stairs ferrying hot drinks and towels and a hair dryer from her to them below, in a silent pantomime. Clothes are flung over the backs of chairs and soon De Rightest Place is transformed into a refugee camp. The rising water laps against the street door where towels rolled along the bottom edge yield to the onrushing tide and seepage rises first an inch, then several.

And then the lights go out. Oh! A huge collective gasp. Then, anybody have matches? Who have a torchlight? Where the door? Don’t step on my foot. Watch where you going.

Be quiet a minute please. No need to panic.

A male voice rises over all and there is a hush. She knows it is his voice, though she hasn’t heard it before. He continues.

Miss Indira, you have candles?

Yes.

You know where to find them?

I think so. They’re upstairs. I think I can feel my way up.

When a wavering light floats down from above, the more superstitious make the sign of the cross across their chests as the reflex thought soucouyant flashes across dark-scared primitive regions of the brain. But no, it’s only Indira, who hands round a packet of a dozen candles and a box of matches, and soon there are candles on the tables, people are sitting around flickering flames like in a cave of much, much earlier times, relating, through rumbling thunder and flashing lightning, competing and complementary stories of famous power cuts, legendary floods, memorable Easter weekends, while the rain continues outside and the waters rise inside. And then a silence as compelling as noise, as the rain stops as abruptly as it started.

The hostages to inclement weather step tentatively down from their chairs, wade with care through the calf-deep water, open the doors and peer outside. Road and pavement, drain and verge are one. All is one sheet of still water in which the newly waning full moon, a melting disc the lustre of white gold, seems to lie just below the surface of the water, gilding it in concentric rippling circles, and all is calm and all is bright. They emerge, holding hands, feeling for where door sill ends and pavement begins, where pavement ends and curb drops to street. Her guests, a flotilla of silent canoes, drift over the moonstruck water and Jah-Son says, goodnight, Miss Indira, thank you for everything, Happy Easter, as he too leaves with the others.

She watches him, his retreating back as he leads the way, finding for his followers, the obstacles, the hazards, the sudden drops in that waterscape of undivined bathymetry beneath the calm smooth surface. And she is washed with an old familiar sense of desolation, at not being one with the people she finds herself among. She is but one stop on their way to their destinations. She watches them as they wind their way homewards in a reflective awe-struck silence.

•

The following morning is Sunday, and there is sun. The scene of wreckage inside and out greets Indira as she surveys De Rightest Place and its Belmont corner space. The Valley Road is a road in name only. It is a rutted-gutted, gouged-ploughed, trenched-wrenched surface. The water having now drained off, the Circular Road is where everything has come to rest, creating a new topography. She walks along mounds of indistinguishable rubbish, moraines of mud, long trailing eskers of branches and twigs, trapped residual pools, car tyres. Here a broken plastic chair, there the rusted door of a fridge. Deflated black garbage bags freed of their contents, a frying pan, its teflon coat pitted, a blue tricycle looking quite serviceable and, grinning up at her from the debris, the rictus smile of a pair of gleaming false teeth. The stench of long forgotten discarded things, of dead animals cast into drains, chicken guts and duck feathers, disposable diapers for young and old disgorged from the underground drains where they had accumulated, fills every crevice of the air. Indira stands on her threshold and wonders what perfumes and unguents would have been used this day, those millennia ago, to mask that smell, perhaps like this one, that would have wafted from the sepulchre when the stone was rolled away after three days, if he had not got up, pushed aside the barrier, and walked away himself.

With that thought, she looks up again at the Valley Road and sees, loping in long strides, that boy, the young man of the night before, the one who took charge, the one they called Jah-Son, and he is looking at the ground, finding secure foothold, as he leaps from one ridge to the next, making quick headway along that impassable roadway, and she turns away to go inside so that he does not see her watching him, does not see her neck flush and her face redden, does not see her eyes widen and her eyelids flutter. She feels a surge in her chest, a pulse throb in her loins. What is going on with me? This is a boy!

Inside she pushes the tables along the wall and begins to stack chairs on to the tables in preparation for sweeping out the water that has pooled a foot and a half deep in the pub. Bet you my horoscope for today telling me to rely on my own resources. Indira smiles wryly at her own prediction and is still smiling when a shadow at the door causes her to lift her head from pulling a table and she sees that young man, Jah-Son, the one of the night before, the sight of whom, five minutes earlier, made her belly flip. He is standing there, knocking at the open door and smiling back at her and his smile pulls a bigger smile right across her face as she raises her eyebrows in surprise, her eyelashes doing their dance.

Want a hand, Miss Indira?

She doesn’t speak. Her voice won’t come out. She lifts her shoulders and spreads her arms wide in front of her, palms up as if giving a benediction. He looks around the pub, lifts his head and laughs, a laugh so deep and full and rich that it fills the room with a warmth that drives out the pall of damp and desolation that hangs there, with an energy charged with the strength of his white teeth, the firm lines of his jaw, the power in the tendons of his neck, and Indira feels her spirit infused with a lightness of being that was almost like being young and as hopeful as youth is said to be, and she’s sure that all will be well. He comes over to move the table himself. Together they work without talk, piling tables and chairs, sweeping out the malodourous water, scraping off mud, hosing down furniture and walls and floor, dragging out on to the pavement soggy cardboard boxes of pulpy books and ruined rugs, soaked appliances and spoiled foodstuffs.

As they work, the rectangle of light framed by the open doorway shifts from the right of the room to the middle, and is over to the left before they are done with the cleaning and restoring the pub to some semblance of normalcy. Even so, business can’t resume. The electricity hasn’t yet come back, the drinks are warm and few and there is no ice. The water too has not come back. The tank they were drawing down would by now be almost empty. But, as they stand and look at the result of their labour, a wave of gratitude washes over Indira. This boy has come to her as her helpmeet again. She has a sense that she has willed him out of the ether, as if he’s had no life before she first saw him and he will disappear once she’s finished with him. She must keep him for a while longer. She smiles at him.

Hungry?

Could do with something, yes.

Come upstairs, let’s see what I can find.

Upstairs, he won’t sit. He’s too dirty, he protests. He’ll mess up her nice furniture. You have bread? Cheese? A sandwich would be fine. You don’t have to cook anything. I’ll be all right. No, no, no. You’ve been working hard all day. You must be starving. I can do better than a cheese sandwich, she insists. Look, tell you what. Why don’t you have a shower, then we can sit properly and eat something more substantial. We can have an omelette with a little salad and some toast. There’s lots of man clothes you can change into after. Come, let me show you where.

What is she doing? Why him? She doesn’t want to go where, in her head, she knows this is leading. So many rituals in this island place point to where her head tells her she’s going.

Is like J’Ouvert morning and you in a mud-mas band and what you looking for? You looking for a clean wall to smear with defiant mud, handprints, footprints, the unique identifiable traceable stuff — is me! You looking for a clean, freshly painted surface on which your earth tone body can leave the imprint of its painted pelt. You is a blue devil. Who you looking for in the crowd? See that one in the carefully selected freshly laundered and ironed outfit? Yes. Rub up on the arms, rub up on the legs, the nice clothes, paste the face, the body with your blue-painted body. You holding the spray bottle of coloured water at Phagwa. No pristine white outfit who trying to run away, to hide, is safe. The urge to desecrate, to sully, is let loose in the madness of sanctioned release, pre-Lenten, pre-spring. You lay claim to the wall you have sullied, the body you have blued, the clothes and skin and hair you have stained — I’ve left my mark. It is me who was there. The graffitist knows the burning compulsion to say his say, leave his stamp, mark his territory, the spoor of two-legged beasts — Kilroy was here.

And she. What does she want of this boy with his mother’s milk still on his tender face? She leads him to the shower in the guest bedroom. She turns on the water in the stall and adjusts the temperature. She leaves him, saying that he should get in while the water’s still hot, there won’t be much left with the power gone so long. Ten minutes later, she gives a little knock and opens the door. He has just stepped out of the shower and she has brought him a towel, one as large and as soft as the one she’s herself wrapped in.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, October 2015

Barbara Jenkins is a Trinidadian writer, author of the short story collection Sic Transit Wagon. She was the winner of the 2013 Hollick Arvon Caribbean Writers Prize, among other awards, and is currently completing her first novel.