Grandfather’s backpay

By F.S.J. Ledgister

Britain’s Black Debt: Reparations for Caribbean Slavery and Native Genocide, by Hilary McD. Beckles

(University of the West Indies Press, ISBN 9789766402686, 248 pp)

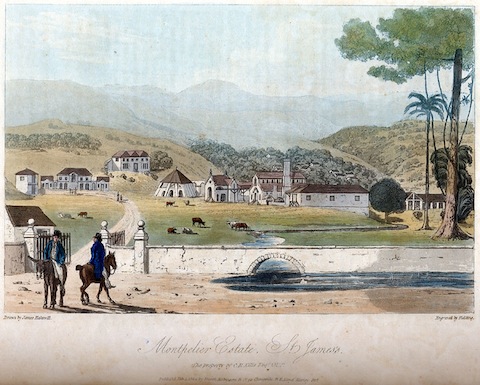

Montpelier Estate, St James, from A Picturesque Tour of the Island of Jamaica (1825), by James Hakewill

At the end of the 1975 BBC docudrama series The Fight Against Slavery, a slave, commenting on the £20 million paid in compensation to slave-owners by the 1833 act abolishing slavery, says (I quote from memory): “twenty million pounds for dem, not a penny for us!” It exposes one major aspect of the issue of reparations with simple clarity: the criminals, to the very end, profited from the crime of Transatlantic slavery in the British West Indies; the victims of the crime have, to this day, received no redress.

The idea that the descendants of enslaved Africans should receive reparations for slavery has been endorsed by no less a figure than the libertarian philosopher Robert Nozick, in his magisterial tome of individualist theory Anarchy, State, and Utopia (1974), as a means of resolving the racial question in the United States. That someone who was no particular friend of black people four decades ago supported the concept of reparations should tell us something about the persistence of this idea.

Sir Hilary Beckles is one of the most distinguished West Indian scholars of our era. That he has taken up this subject, and done so with a combination of scholarly rigour and activist urgency, is part of an important and growing movement to demand not only recognition for one of the greatest wrongs ever committed in history, but redress for that wrong, and reconciliation between the descendants of the wrongdoers and their victims. In this relatively short work, Beckles is focused on Britain’s historical relationship with its Caribbean empire and how that empire permitted Britain to build its prosperity between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, both on the sweat and blood of Africans whose enslavement meant every possible form of violation, and on the extirpation of the aboriginal inhabitants of the Caribbean.

Reparation for these wrongs, Beckles argues, would produce reconciliation and “a spirit of mutual respect and obligation between the British state and the descendants of enslaved Africans.” The peoples of the Caribbean have been the victims of two monstrous crimes against humanity — the genocide of the original inhabitants and “the mass enslavement of Africans” — and have experienced “lasting and damaging effects in the psychological, material, and social conditions of those victimised and on generations of their progeny.”

Britain, as the greatest imperial power, the biggest slaver, the largest profiteer of imperialism, bears the most actual blame for this record of inhumanity: that is to say, for what, as Beckles points out, older Barbadians once called “barbarity time,” the epoch of slavery, which has conditioned our history both generally and personally. For Beckles, as a West Indian historian, the issue is “both professional and personal,” and he notes that he has discussed the matter with a number of activists and scholars over the years. The present study, he writes, came at the urging of “legendary Jamaican pan-African activist” Dudley Thompson. His deepest intellectual debt, however, and one freely acknowledged, is to the father of West Indian historiography, Eric Williams.

The heart of Beckles’s argument is Williams’s in Capitalism and Slavery: that West Indian slavery built British capitalism. He makes clear that the debate over Williams’s thesis is not simply black West Indians versus white Europeans and North Americans, but is, in fact, a debate between two very different perspectives. Williams had marshalled the data to show how valuable the sugar colonies were in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and how the super-exploitation of black slave labour produced immense wealth for Britain and made possible the industrial capitalism that turned Britain into the Top Nation of the nineteenth century.

The first part of Britain’s Black Debt is Beckles the historian walking very much in the footsteps of Williams and showing how the British turned the extirpation of the indigenous people of the eastern Caribbean and the exploitation of the approximately three million Africans brought to the British West Indies into profit. It is the history of the West Indies that we learned in school, but from the perspective of the institution of slavery. So we are shown slavery as the brutal dehumanising institution that it was, with chapters on such subjects as the deliberate classification of Africans as less than human, the prostitution of slave women, the case of the slave ship Zong — in which the deliberate jettisoning of healthy Africans within sight of Jamaica was not treated as murder, since the court in London considered the slaves thrown overboard to drown or be eaten by the sharks were mere chattels, rather than human beings — and on the compensation of slave-owners at Emancipation.

Particularly intriguing is the chapter on the Anglican Church’s slave-holding practices in Barbados, though Sir Hilary notes that 128 Anglican clergy were compensated for property in slaves throughout the West Indies at Emancipation, almost half of them for slaves in Jamaica. Beckles reports that the Anglican bishops who were responsible for the Church’s estates in Barbados believed that “slavery and Christian conversion had to be handled with no threat to the financial soundness of the business.” Doubtless the Christian thing to do.

Throughout the historical account that Beckles lays out for us, there are clear echoes of Williams’s approach to the subject of slavery, and of the British role in West Indian slavery, in both Capitalism and Slavery and British Historians and the West Indies. Thus, both Williams and Beckles take note of the role of the British aristocracy as plantation owners and defenders of slavery in Parliament.

In the second part of the book, which is far shorter than the historical account, Beckles turns to an argument for the case for reparations, to discussion of British policy — in the light, in particular, of the parliamentary debate on the bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade in 2007 — as well as to the debate on reparations that occurred at the World Conference Against Racism, Discrimination, Xenophobia, and Related Intolerance held in Durban, South Africa, in 2001, and to the emergent Caribbean Reparations Movement.

In arguing for reparations, Beckles is clearly moved by a depth of emotion which any West Indian, regardless of heritage, can understand. His contention is clear: “The case for reparations should be made against the British state and a select group of its national institutions, such as merchant houses, banks, insurance companies, and the Church of England. These institutions exist today. Their slave-derived wealth is not in question.” Indeed, the history he recounts in the earlier chapters served to demonstrate that. What is also clear is that scholars, businesspeople, and statesmen throughout Britain’s imperial history “were unified in recognising slavery as the primary stimulus to the national economy.” In the modern era, British officialdom has sought to place slavery in the remote past, and to argue that it was too large a system to make it possible to construct any structure of reparation. Britain has responded to demands for reparations, essentially, by moving the goalposts and by seeking to intimidate those who have been making the demands.

For their part, Beckles declares, “Caribbean governments have a legal, diplomatic, and ethical obligation, within the finest traditions of British jurisprudence and politics, to assist the British state in accepting responsibility for its actions and so becoming accountable.” However, as his account of the UN’s 2001 World Conference Against Racism indicates, the Caribbean, though able to unite to demand reparations, could not overcome a united Western voting bloc and African disunity — especially, as he notes, the willingness of Nigeria and Senegal to side with Britain and the United States.

Britain’s debate on the subject, Beckles reports, has been characterised by a marked unwillingness either to apologise for slavery or to negotiate on reparations. This was particularly acute during the commemoration of the bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade in 2007, when British Prime Minister Tony Blair rejected calls for an apology, and black members of his government, of West Indian birth or origin, supported his argument that slavery was legal at the time. Rather than apologising, the British government issued a “statement of regret” about slavery. Beckles notes that paradoxically there was a parliamentary debate which impressively ventilated “Britain’s crime against humanity,” but which did not “take the next step of ownership, apology, and commitment to repair.”

Beckles’s final chapter, on the Caribbean Reparations Movement, discusses not only the issue of slavery in the British Caribbean and responses to it, but such related matters as the reparation bond inflicted on Haiti by France and the forced exile of Haitian president Jean-Bertrand Aristide, as well as the expulsion of white delegates from an anti-racist conference held in Barbados in 2002, which was condemned by the Barbadian government. He also notes that the 2007 bicentenary of the abolition of the slave trade was commemorated very differently in the West Indies than in Britain: in the Caribbean it was the basis for calls for reparation, the strongest of which came from Guyana’s then-President Bharrat Jagdeo. It is noteworthy that Beckles does not point out that neither Jagdeo nor Vincentian Prime Minister Ralph Gonsalves, whom he also cites as an advocate of reparations, is descended from enslaved Africans.

Unfortunately, this final chapter of Britain’s Black Debt simply peters out, and we are not given a conclusion that would completely round out the monograph. This is a pity, as the concluding chapter begins strongly by reminding us that the reparations movement is about both slavery and the genocide of the indigenous peoples. Nonetheless, Beckles has provided us with a powerful, historically grounded manifesto that, in the tradition of Eric Williams, serves both to educate and to mobilise. I am certain the Doctor would approve.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, August 2015

F.S.J. Ledgister is a British-born Jamaican. He teaches political science at Clark Atlanta University in Georgia, and has published work on Caribbean political development and political thought, and a digital collection of poems, Mango-Red Leaves.