Into the dark waters

By Nishant Batsha

Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture, by Gaiutra Bahadur

(University of Chicago Press, ISBN 9780226211381, 312 pp)

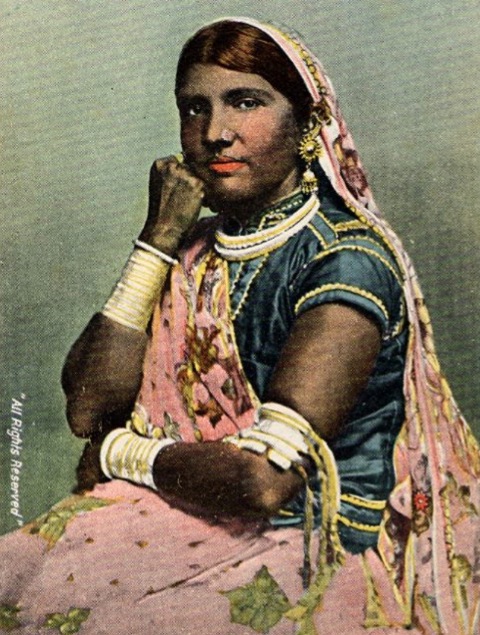

Detail of East Indian, Trinidad, B.W.I., a postcard from the Michael Goldberg Collection, courtesy the Alma Jordan Library, University of the West Indies, St Augustine

“Peasants do not write, they are written about. The speech of humble folk is not normally recorded for posterity, it is wrenched from them in courtrooms and inquisitorial trials. Historians have therefore learned to comb ‘confessions’ and ‘testimonies’ for their evidence, for this is where peasants cry out . . .”

— Shahid Amin, Event, Metaphor, Memory

Anyone who has spent any number of hours holed away in an archive can speak of the ways in which it drives one mad. There exists the usual catalogue: irascible archivists, stuffy historians shuffling about (everyone but oneself is a stuffy historian in the archive), or too-loud conversations on unsilenced mobile phones. But beyond these annoyances lie one true maddening fact: rarely, if ever, do the documents in the chambers of the archive hold the voices of the everyday. The voices of peasants and everyday people do crop up from time to time, buried deep in court documents or government inquiries. And in between? Silence.

Academics tend to call these types of silences lacunae. The term literally refers to missing or blank portions in a manuscript. It’s a fitting word. It comes from the Latin for “hole” or “pit.” In any case, only a deft writer and historian can resist the call to madness and navigate an archive filled with blank spaces. We can be thankful to have found her in Gaiutra Bahadur.

Bahadur begins Coolie Woman not with such silences, but with the cacophony of her family’s 1981 departure from Guyana for New Jersey. The disconnect experienced by immigrants in a new country is heightened in her case. Not only did she have to balance an Indo-Caribbean and American life, but she had to do so while constantly being reminded by other Indians (from India) that her culture was familiar, but somehow “off.” Using the West Indian terminology of children born outside legal marriages, Bahadur found that “To some, we are India’s outside child. When class isn’t their issue, authenticity — some apparent concern over our parentage — seems to be.” But for Bahadur, the Caribbean remains an authentic historical fact of origin and upbringing. Amid all this, a childhood trip back to Guyana led her to “ask about another, more epic journey.” The journey was that of her great-grandmother, Sujaria.

Sujaria was a migrant indentured servant. The history of coerced labour in the British Empire did not end with the 1834 abolition of slavery. By 1838, colonial administrators and plantation owners devised a system for the transportation of indentured Indian labourers to Mauritius and the West Indies. By its end in 1920, almost two million Indians had been recast as “coolies” and sent to labour on plantations in colonies in the Caribbean, South and East Africa, Southeast Asia, and the South Pacific.

Catalogued in the archive as “Immigrant #96153,” Sujaria left Bihar — one of modern India’s poorest states — in 1903 on the ship The Clyde. When she left, she was issued an immigration pass. This document listed an immigrant’s age, sex, height, distinguishing mark, caste, father’s name, spouse, and home village. Someone had scribbled in the margins, “Pregnant 4 mos.” As for a husband’s name, there was only a dash. In her book’s preface, Bahadur writes, “My great-grandmother was a high-caste Hindu. That is a fact. But she left India as a ‘coolie.’ That is also a fact.” But what could drive a high-caste pregnant woman to board a ship alone to travel across the world to labour on a five-year indenture contract in dehumanising conditions on a sugar plantation? What was her life like?

Armed with such questions, one could enter the archives hoping for a eureka moment: an interview with Sujaria, a one-paragraph summary, anything. Yet, all that remains (for Sujaria, or for anyone else’s great-grandmother) are the crumbs of government documents: inquiries, testimonies, and court cases. If humble folks do not record their own voices for posterity, women — humble or otherwise — are perhaps doubly erased. Even with such limited raw materials, Bahadur is able to write a history not only of Sujaria, but also of how all Indian woman may have lived through the harrowing experience of indenture.

For example, in the chapter “Her Middle Passage,” Bahadur seeks to understand her great-grandmother’s journey across the ocean. “Sujaria spent three months and a week in that iron belly,” she writes, noting, “Without the official chronicle of Sujaria’s journey, I had to seek proxies for her in the records.” In this case, the chapter begins with the story of The Main, which set sail in 1901. On board was Albert Stead, a seaman from Guiana. The ship’s surgeon had caught Stead trying to sexually assault an immigrant woman near the latrines. When the captain later tried to discipline his officers for “loll[ing] about the main hatches or the latrines,” Stead exclaimed, “What, fine us for talking to a coolie? You can’t do it!” In response to such insubordination, the captain ordered handcuffs be brought, leading to a scuffle between half the ship’s sailors and the captain. In the melée, both the ship’s second and first mates brandished the handcuffs in front of the insubordinate sailors. In spite of such a call to authority, both had abused women on board, and one had forcibly fondled the breast of an immigrant. “This was the man,” Bahadur writes, “who rushed to handcuff Stead as the showdown on deck reached a crisis, with the captain encircled.”

These were the conditions of the journey. The destination, however, held a modicum of promise. “New hierarchies emerged across the dark waters,” Bahadur argues. “Coolie women could leave their husbands, and they could partner across caste.” While this sexual leverage did exist, Bahadur finds that any promise in Sujaria’s world was counterbalanced by great pain inflicted upon the body. “The weeks and months of my great-grandmother’s first year in Guiana,” Bahadur writes, “had passed in unrelenting violence.” In a powerful section of the book, Bahadur lists, from 31 October, 1903, to 29 October, 1904, seventeen instances of court cases of “wife murder” and violence against women, or the concomitant executions of the men who committed such abuses. Women like Sujaria were confronted with extraordinary violence at every turn. And yet some were able to thrive. Sujaria lived well into her eighties. Her son, born at sea, outlived her by only a year.

Nevertheless, one is always left with the situations around which her great-grandmother crossed the world. We may never know of her exact circumstances before, during, or after her indenture. Bahadur does not shy away from this mystery. When considering why women left India for the indenture colonies, she writes

What, then, was the truth? Into which category of recruit did my great-grandmother fall? Who was she? Displaced peasant, runaway wife, kidnap victim, Vaishnavite pilgrim, or widow? Was the burn mark on her left leg a scar from escaping a husband’s funeral pyre? Was she a prostitute, or did indenture save her from sex work? Did she see herself as part of the subcontinent’s own version of the “Fishing Fleet”? Did the system liberate women, or con them into a new kind of bondage? Did it save them from a life of shame, or ship them directly to it? Were coolie women caught in the clutches of unscrupulous recruiters who tricked them? Were they, quite to the contrary, choosing to flee? Were these two possibilities mutually exclusive, or could both things be true?

Few historians could stand such queries. Most mine the archives in search of easy answers to easy questions. What did the governor of British Guiana say on such and such occasion? What were the laws relating to wife murder in 1904? But Bahadur did not write Coolie Woman to answer those questions. In seeking out her great-grandmother and the thousands of women who left India to labour abroad, Bahadur discovers that only some narratives can be found. Others, however, can only begin and end in question marks. She knows such punctuation invites the reader into a moment of pause — of awe, of horror, of wonder. In that pause, the reader realises that while she may never read what Sujaria said, she may do well to conjure in her mind’s eye the place and conditions in which she lived. These are the histories that are powerful — and needed.

The Indians who left for the indenture colonies were said to have crossed the kala pani. Crossing the dark waters meant risking losing one’s caste. In Sujaria’s case, “Coming from the world she did, where community was life itself, she must have feared that the dark waters would swallow her very self and soul.” In writing Coolie Woman, Gaiutra Bahadur did not fear the kala pani — that endless stretch of ocean with its deadened quiet. Instead she committed to finding again the voices of those aboard countless ships, whose whispers were sent into nights spent surrounded by dark waters. She has plunged into those depths. She has found us stories worth telling.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, August 2016