Make you real

By David Knight, Jr.

Land of Love and Drowning, by Tiphanie Yanique

(Riverhead Books, ISBN 9781594488337, 358 pp)

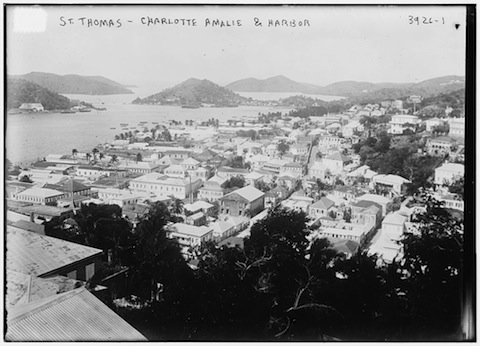

Charlotte Amalie, St Thomas, around the time of the transfer of the Virgin Islands from Denmark to the US. Photograph by the Bain News Service, posted at Flickr by the Library of Congress

Anette Bradshaw, the most memorable of the narrators of St Thomian writer Tiphanie Yanique’s novel Land of Love and Drowning, is born between two disruptions. The first of these is one of Caribbean history’s peculiar fissures: the sale of her home island to the United States by Denmark in 1916. The second, the death of both her parents, is a personal tragedy. The proximity of the two events, and the instability they represent, leads Anette to conflate them: “Those two things, orphan and American, always seem the same to me,” she says. Like many of the characters who populate Yanique’s contemporary creole parables, Anette is a woman adrift, unmoored from community and often at odds with what is accepted as history.

Yanique, from the start of her career, has shown an interest (perhaps too mild a word) in expressing an American colonial ontology. The US Virgin Islands, the unincorporated territory that is her home ground, is not so much a geographic location or political reality in her writing as it is a way of being. “When you think about this particular place, the US Virgin Islands, you think about the ‘US’ in the front. What does it mean to be American in this very specific kind of way?” Yanique pondered in a 2014 interview in the Los Angeles Review of Books.

Indeed, those two small letters that announce the boundaries of one half of the Virgin Islands represent relatively unexplored territory in Caribbean fiction. Land of Love and Drowning is an ambitious, urgent, and sometimes uneven first novel birthed from the contradictions of a place that is, politically speaking, less than a century old. From bits of local folklore, oral history, and postcolonial theory (faded and worn in places, but still perfectly relevant to the Virgin Islands), Yanique has constructed a chronicle of one St Thomas family’s experience of the twentieth century.

Yanique’s formula is inventive but self-conscious. As a member of a young generation of Caribbean writers embedded in universities since the beginnings of their careers, she can be motivated by theory to the point of raising a knotty question: how does self-awareness change the self that has become aware? The pages of Land of Love and Drowning are crowded with intertextual references and narrative experiments that owe as much to Caribbean studies as they do to Caribbean imagination. All that is to say that Yanique’s prose only sometimes succeeds in masking her attraction to academic ideas.

Even if its seams are visible, Land of Love and Drowning’s construction never gives the impression of roughness or crudeness, thanks in large part to the fable-like intimacy of Yanique’s writing and its subtle shifts in narrative voice. Two of the book’s most important narrators, Anette and Eeona Bradshaw, the very dissimilar daughters of a prominent St Thomas family fallen on hard times, give Yanique plenty of opportunity to experiment with style. Through their antithetical voices, as well as the interjections of a nameless chorus of St Thomas “old wives,” Yanique charts a history of the US Virgin Islands that presents an alternative to the insistent American narratives of the status quo.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the voice of Eeona, the elder Bradshaw sister, is far less alive in style than her younger counterpoint. Eeona represents a fading world of upper-crust Danish West Indian gentility, her aristocratic sensibility rendered obsolete by a new American reality of racial binaries and the breakdown of an old class order that once gave her privilege. It is her little sister Anette, who speaks in a loose, energetic St Thomas dialect, who is the heart and soul of the novel. Anette is the first of a new generation born under the American flag and, consequently, either a new nation or no one.

“On Transfer Day everybody gone to the military Barracks,” says Anette, “and wave toonchy American flags and wonder if our VI could ever become a US state. Only now that I is a historian myself, I could look back and really see that it was a funny thing happening that day. The land and the people like we going separate ways. The land becoming American, but we people still Caribbean.”

•

There is a lot to be packed into the decades that Eeona and Anette and the anonymous “old wives” narrate — wars, the birth of mass tourism, the American Civil Rights Movement — and the signposts of this period are laid out by Yanique for what they have meant to Virgin Islanders, often not so easily accommodated by broader US national narratives. Yanique’s complex and essentially creole relationship with history is a skepticism that occasionally borders on antagonism. As Anette, the book’s self-identified historian, puts it:

“I just saying that given what we know about the place and about the time, my version seem to have a truth in it somewhere. Is just a story I telling, but put it in your glass and drink it.”

Time is compressed in Land of Love and Drowning to the point of disorientation, a technique that Yanique employs for philosophical and critical reasons. The seven decades in which the novel is set sometimes seem to liquify into a single indistinct time period. The Virgin Islands myths which Yanique introduces into the story — the Cow-foot Woman, Anansy stories — further disturb any attempt to locate the Bradshaw family in a conventional chronology.

Yanique has also mined her own family history in places, and in this way the novel owes something to that natural Caribbean genre, the family epic, of which V.S. Naipaul’s A House for Mr Biswas remains the sublime example. This is an intelligent choice on Yanique’s part; after all, where does one start when re-imagining the story of a place, but from re-imagining one’s own ancestral narratives?

Most extraordinary of all of Land of Love and Drowning’s investigations of twentieth-century Virgin Islands-ness is its dialogue with another work, the Herman Wouk novel Don’t Stop the Carnival, which Yanique has described as “the Passage to India of the Virgin Islands.” “If people outside of the Virgin Islands have read any book about the place,” she says, “that’s the book they’ve read. And when newcomers want to learn more about the Virgin Islands, their fellow settlers read that book and share that book with them.”

Wouk’s comic novel, set in a fictional version of 1960s St Thomas called Amerigo, is the best example of the sort of novel written by a half-transient group of mainland immigrants whose comedic sensibility derives from a naive bafflement in the face of the American colonial situation. Wouk is one of the few authors of this sort of book who has sustained a reputation on the strength of his writing, and consequently Don’t Stop the Carnival has survived in some circles as a sort of authoritative literary representation of the USVI.

Yanique corrects — or, to put it more accurately, balances — some of the impressions that linger in Virgin Islands literature due to Wouk’s book. In her novel we find the same period presented from an alternate point of view. Certain characters from Don’t Stop the Carnival appear in Land of Love and Drowning and are given new dimensions. The continental (a Virgin Islands term for mainland American) characters are those on the margins of the story, rather than native Virgin Islanders, who have regrettably been represented in questionable ways in many books that find an audience beyond the territory.

If Yanique has over-corrected in response to Wouk — where Virgin Islanders are buffoonish in Don’t Stop the Carnival, continentals are equally one-dimensional in Land of Love and Drowning — the reasons seem acceptable enough. But there are times when Yanique’s novel recalls Edward Said’s assertion that the first stage of the decolonisation of a national literature only hints at “the possibility of discovering a world not constructed of warring essences.”

One of Yanique’s characters in her 2010 collection of short stories How to Escape a Leper Colony remarks, “When someone know you it make you real.” It is hard to imagine Yanique’s quiet, reflective prose without that same turbulence beneath it: the hunger for recognition, the thing that makes us real. If she someday writes the great Virgin Islands novel, we will have that hunger to thank. Until then, she deserves praise: she has undertaken the brave task of “writing back” to an empire that is, importantly, still discovering the dissenting voices within itself.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, August 2015

David Knight, Jr, is a writer from the US Virgin Islands, and the co-founder and co-editor of the journal Moko. He is currently collaborating on an overview of art history in the Virgin Islands.