In praise of Colly

Edward Baugh on Frank Collymore and the making of West Indian literature

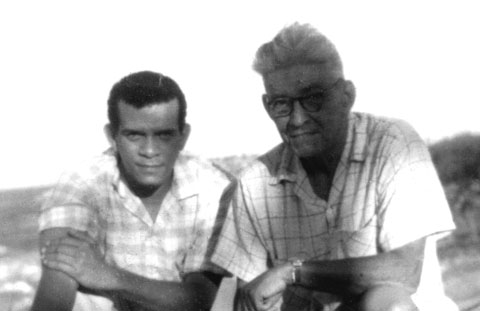

A young Derek Walcott with Frank Collymore in Barbados. Photograph courtesy the Estate of Frank A. Collymore

When I first arrived in Barbados, in January 1965, to teach at the Cave Hill campus of the University of the West Indies (then located at the Deep Water Harbour), I arrived with feelings of lively anticipation. One reason for this anticipation was the fact that I was arriving at the source of the little magazine Bim, to which I owed much of my sense of the flowering of something that could be legitimately called West Indian literature.

I can’t remember how I first got to know about Bim, but what I do remember is dipping into it when I browsed the periodicals stacks of the library at the Mona campus between tea time (or lemonade time) and dinner time, when I was an undergraduate, and later graduate student. Bim was published twice yearly, and I recall looking eagerly for each new number when I thought it was about due. A special memory, which has about it a kind of Saul-on-the-road-to-Damascus quality, is of opening the then latest number — No. 26 (January–June 1958) — and stumbling on Walcott’s sonnet sequence “Tales of the Islands”. Because of the impact of those poems, I wrote a short article for the student magazine, The Pelican. The article began: “The most interesting item in the latest issue of Bim . . . is ‘Tales of the Islands,’ a sonnet sequence by Derek Walcott.” It was not a review of that issue of Bim. It was strictly about the Walcott poems.

Anyway, a few weeks after arriving in Barbados, I decided to chance my arm and send some poems to Bim. Contributions had to be sent to “The Editors of BIM, Woodville, Chelsea Road, St Michael.” I received a reply dated February 24, 1965, and it went like this:

Dear Mr Baugh,

Thank you very much for submitting us your three poems. I am greatly impressed by them and shall most certainly be using them in our next issue.

Our idea is — should we receive a reasonable number from our poets (Walcott, Morris, Brathwaite, et al) — to lump the poems together under some such title as “Caribbean Sampler” or something appropriate instead of printing separately. This would depend also whether the poets were all West Indian.

I wonder if you would be kind enough to let me know — since your name is unknown to me — whether you are W.I. or not. If the latter, this would not of course stand in the way of publication; this will be done in either case.

Thanking you again,

Yours sincerely,

Frank Collymore

for

the Editors of Bim

Two facts that were to be confirmed soon enough probably began to suggest themselves to me from this letter: one, that “the Editors” of Bim were really, for all practical purposes, Frank Collymore; and two, that Woodville was the Collymore residence, the house where he was born and where he had lived all his life. The letter also confirmed how focused Bim had become on its West Indian commitment.

A year later I submitted another poem, which he also accepted. This time his letter ended with an invitation: “I was wondering whether you would like to drop in some afternoon for a chat and a drink. You can always give me a call

. . . by phone.” That was the beginning of our friendship. I soon became actively involved with the Green Room Theatre, of which Collymore was the Grand Old Man. That same year, 1966, George Lamming was invited to be guest editor of the Barbados Independence Issue of the magazine New World. He in turn invited me to be his associate guest editor and to write for the issue an article which appeared under the title “Frank Collymore and the Miracle of Bim”. I felt greatly honoured. My one subsequent regret was that I didn’t realise at the time that the individual I should have interviewed most closely about Collymore, apart from Collymore himself, was Lamming; but Lamming was not the sort of person who was likely to tell me that. That article was my first substantial one on West Indian literature. It marked the beginning of my shift of research focus from late Victorian British literature to West Indian literature.

I have told this little story in order to give a personal grounding to the larger story I’d like to outline, to bear personal witness, as it were, to the generosity of spirit and the spiritedness which Frank Collymore brought to the role that history called him to play in the emergence of West Indian literature at a crucial juncture. He made his signal contribution in two ways: first, through his own poetry and short stories, and, second, through his editing and publishing of Bim and, over and above that, through his promotion of and selfless assistance to certain young contributors to Bim, some of whom were to become classics of West Indian literature. We should not underrate his own writing, relatively minor in the overall scheme of things, but appreciable and significant. However, the more epoch-making achievement was his work with Bim, and Collymore’s Bim-related dealings with so many young men who were to play so great a part in the making of West Indian literature.

•

Bim came along at just the right time to meet a simmering need. Launched in 1942, it started out as a Barbadian magazine. That it soon enough began to look outwards, to the wider Caribbean, was the result not only of opportune circumstances, but also of Collymore’s receptivity to the spirit of the time. In “The Story of Bim” (1964) he wrote that, on his return from a visit to the United Kingdom in 1947, as a guest of the British Council, he found himself aware of

a change in outlook. The West Indies had come into the news. The conference at Montego Bay seemed to point to a federation of the British West Indies. I found myself enthusiastic for contributions from the islands, and I was not disappointed. During the years that followed we were publishing material from Trinidad, Jamaica, British Guiana, St Vincent, St Lucia.

No. 9 (December 1948) marked a decisive development. It carried poems by three Trinidadians — C.L. Herbert, Harold Telemaque, and Ruby Waithe — an essay by a fourth, Ernest Carr, and a short story by the British Guianese Edgar Mittelholzer. In a whimsically happy “Foreword”, the editors (meaning, of course, Collymore) made a point of remarking on this development:

But, alas, we are losing our insular self-sufficiency. A glance at the contents of this volume will discover the names of many contributors who dwell beyond these shores . . . Yet, despite this blow to our pride, we take very great pleasure in introducing to our readers a group of five writers from Trinidad.

That Collymore identified five writers from Trinidad was, in a way, an indication of the spirit of his regionalism. He was counting not strictly in terms of country of birth, but also of domicile. Lamming had recently gone to work in Trinidad, where he was soon spreading word of Bim, selling the magazine, and rounding up contributors. So, to complete the whimsy, the “Foreword” added: “There is, however, one ray of consolation here — Mr Lamming is by birth Bim.” As for Mittelholzer, he had been appearing in every issue since No. 5 (February 1945), although at first Collymore knew nothing of his country of origin. He had apparently first discovered Bim on a holiday in Barbados, and had begun to send in short stories.

No. 10 (June 1949) was a landmark. The West Indian dimension and commitment, now decisively widened, were proclaimed on the front cover, where contributors were grouped according to country of location rather than birth. Barbados had the largest number, twelve, Trinidad six, Jamaica and St Lucia two each, and British Guiana one. After No. 10, there was no going back on the West Indian project. The most considerable writers thrown up in the first great wave were Lamming, Walcott, Brathwaite, and Collymore, Geoffrey Drayton and John Wickham (as Barbadians), as well as Mittelholzer, Eric Roach, Sam Selvon, A.L. Hendriks, John Figueroa, and Cecil Gray (then a short story writer). Ian McDonald, the Trinidadian-Guyanese poet and novelist, and the Trinidadian novelist Michael Anthony heralded the second great wave, which began with Barbadian novelist Austin Clarke and Jamaican poet Mervyn Morris in No. 35 (July–December 1962), and included short-story writer Timothy Callender (Barbados) and poets James Berry (Jamaica), Slade [Abdur Rahman] Hopkinson (Guyana), and Judy Miles (Trinidad and Tobago), whose bright meteor, like that of Michael Foster (Barbados), burned all too briefly before it disappeared. The Barbadian vernacular poet Bruce St John became, belatedly, a regular contributor in the 1970s.

With regard to the rising spirit of West Indianness, there is a pertinent couple of sentences in a letter from Albert Gomes, the rambunctious, fledgling Trinidadian politician, to Collymore in 1949. Praising Bim No. 10, Gomes says: “You fellows need the support of all those persons in the W.I. territories who believe that art and literature are important. I’ve been discussing this aspect of things with Lamming.” He then tells Collymore that Lamming is thinking of putting out a magazine in Trinidad, and observes: “What we want is not a Trinidad or a Jamaica or a Barbados magazine but a West Indian one, and Bim has already begun to take that shape.”

So many major or significant West Indian writers cut their teeth on Bim. Anyone who wishes to study the development of, say, Brathwaite, Lamming, McDonald, Morris, Mittelholzer, Roach, and Walcott, must look at their contributions to Bim. One will see that Lamming was at first poet, rather than prose fiction writer. If one wants to see the work of a fine short story writer, who might, if fortune had been favourable, have become one of the West Indian greats, one must go to Bim for the pieces by Karl Sealy. There were, of course, major West Indian writers who did not have work published in Bim. One thinks, for instance, of the Jamaican V.S. Reid, and the Guyanese Martin Carter and Wilson Harris.

John Wickham, short story writer, Collymore’s protégé and confidante, and to whom Collymore entrusted the editorship of Bim when he gave it up in 1973, spoke for other eminent West Indian writers when he said, “I owe my friendship with Colly almost entirely to Bim magazine.” And Kamau Brathwaite has written of Collymore:

. . . if he hadnt seen my work as worthwhile & worthy of encouragement — and since I know that there was no other place no other person, who would have published my work in the way he did — with the love, encouragement & continuity he did . . . and if it were not for that, I wonder if I would have persisted with my writing (each time something of mine came out in Bim it was like a big boost for me & I’m sure I speak for others) . . .

Timothy Callender wrote similarly in the special Collymore eightieth-birthday issue of Brathwaite’s Savacou. Referring to his first appearance in Bim, when he was “fifteen or sixteen,” he said:

I was fascinated to see my name in print. It was one of the great moments of my life; I set to work like mad to produce more stories . . . I think too that from early as that you see a talent that I only just begin to believe in meself, and it give me great confidence when I see that you really thought they was worth continuing.

The encouragement and hospitality which Collymore offered to young Bim contributors must have had all the more impact because he was so much older than they; and he made them feel that they were part of a new, exciting community of writers. Brathwaite recalls an occasion when, after his first Bim poem had been accepted for publication, Collymore

stopped his old red Singer sports car outside Round House [the Brathwaite home on Bay Street] one afternoon going home from Combermere & invited me to come chat & laughter at Woodville & meet some people . . .

As Walcott has said,

To be treated at that age by a much older man with such care and love . . . was wonderful . . . He was not by any means a patronising man. He never treated you as if he was a schoolmaster doing you good.

Of the friendships which Collymore made through his editing of Bim, most were developed primarily, and in some cases exclusively, through correspondence. One or two were with persons who, though not themselves writers, were much involved, officially or informally, in the promotion of West Indian literature. Most notable among these was Henry Swanzy, the Irishman who was the main editor-producer of the BBC’s Caribbean Voices programme. Collymore was a great letter writer, usually answering a letter immediately after he had received it. In 1953, Sam Selvon, who had been corresponding with Collymore since 1949, said: “It is only through correspondence that I know Frank, and yet I believe I would hardly have known him better if I were seeing him every day.”

Earle Newton, professor emeritus at the University of the West Indies, tells a particularly appealing story. Though not a writer himself, he had been taught at Combermere School by Collymore, for whom he had the greatest admiration, and who had become his friend. When Newton, as a young graduate, was going to teach in Tobago, Colly gave him a note to Eric Roach, “a good friend of [his].”

Well, I rang up Roach and said who I was and that I wanted to come and see him . . . and he wasn’t particularly enthusiastic until I mentioned Colly, and immediately . . . he was trying to get me . . . to come immediately, and eventually he picked me up . . . and I tell you this, we sat and talked about Colly for ages, and then Roach says to me, “But what does he look like?” They had never met! . . . I remember going back home and visiting Colly and telling him about Roach.

•

To read what we can of Collymore’s correspondence with, notably, Lamming, Mittelholzer, Seymour, Harold Simmons, and Swanzy, is to feel that we are sharing in the excitement of an epoch-making moment, an excitement perhaps all the more real to us who experience it with the privilege of hindsight. One great regrettable loss is that of the correspondence between Collymore and Brathwaite.

Of the writers to whom Collymore’s help and friendship were crucial in the early stage of their careers, I shall confine attention to Lamming and Walcott. At Combermere, young George Lamming found Mr Collymore, the First Assistant Master and his English teacher, the only one of the masters who struck a responsive chord in him, the only one whom he could respect and admire. His literary yearning was seized by the schoolmaster who was not only editor of the bright new magazine Bim, but who also wrote poems. As far as Lamming knew at that time, “Writers lived somewhere else. They were dead, not people you lived with.” Collymore remembered being impressed by the youngster when he was preparing him for the Cambridge School Certificate examination in English. Moreover, as Lamming recalls, Mr Collymore “had a tremendous library which I literally took over. I mean I was there every Saturday morning to collect books, which caused a lot of trouble.” The boy was a voracious and precocious reader. But for Mr Collymore’s intervention, he might have been expelled for reading H.G. Wells’s Outline of History and The Science of Life in his geography and mathematics classes.

On 10 February, 1946, eighteen-year-old Lamming, now having left school, writes to his mentor from his home at Alkins Road, Carrington’s Village, St Michael. He comments on André Malraux’s biography of Shelley, Ariel, which he has just read with enjoyment. He says he is looking forward to a biography of Byron, on whom he comments. He tells his mentor about a movie based on Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, which he has seen, and asks Mr Collymore to tell him about Wilde. He also says that he is sending “some attempts for the coming Bim,” and adds, “I have every confidence in your sympathetic reading. And if you grow haughty with my bad verse, you will find my defence in your own ‘Apologia’,” a poem which he proceeds to quote. This poem, “Apologia”, had not appeared in Bim, but was the opening piece in Collymore’s first collection, Thirty Poems (1944). Lamming had obviously made himself very familiar with Collymore’s poetry.

Lamming then tells Collymore that he will have to come to see him before the week is out. This intention had to do with the impending visit to Barbados of a Professor Negron, on which an employment opportunity for Lamming apparently rests. The letter ends, “I trust your sincerity, and I know you will press my claims for any situation. I hope you are well, and believe me, I am / Yours respectfully / G.W. Lamming.” Early in March 1946, Lamming arrived in Trinidad to teach at the Colegio Venezuela, a school primarily for teaching English to Venezuelans. On 18 March he writes to tell Collymore of his “safe arrival and warm welcome.” A “vigorous correspondence,” to use Collymore’s words, developed between them. He met Mittelholzer, to whom Collymore had directed him, and whom Collymore had alerted to his arrival. Lamming’s letters from Trinidad deal substantially with his reading, his writing, his ideas about poetry, his work on behalf of Bim (both in seeking out contributors and in selling copies of the magazine), and his involvement with the Port of Spain literary circle, including Selvon, Cecil Gray, Cecil Herbert, and H.M. Telemaque.

In 1950, Lamming left Trinidad for London, a move he felt necessary to fulfilling his ambition to be a writer. Collymore helped to prepare the way for him, by telling Henry Swanzy about him, and asking Swanzy to do whatever he could to assist him. That was how Lamming became a reader and presenter on Caribbean Voices. When Swanzy decided to do “A Programme of Greeting for the Sixtieth Birthday of F.A. Collymore, Editor of BIM,” he asked Lamming to script and present the programme. Lamming in turn enlisted the assistance of Selvon. The programme was broadcast on 1 March, 1953.

Lamming’s last letter to Collymore is dated 16 February, 1980. He had been to Barbados earlier in the month to receive the honorary degree of doctor of letters from the University of the West Indies, at the graduation ceremony at the Cave Hill campus. The letter was written soon after Lamming’s return to the United States. In the annals of friendship there can hardly be a more moving summation and tribute, a more authoritative and poignant expression of gratitude. Collymore, because of ill health, had not been able to attend the graduation ceremony. Lamming, after expressing regret that he had not been able to enjoy a longer visit with Collymore, and that time had not allowed them their “usual long, leisurely stroll round old friends,” says that he hopes to be back in Barbados “around the middle of the year.” He grows “more and more attached to the landscape of Barbados” with each return, “the music of ordinary voices, especially the fishermen in Bathsheba where I stay; and also the language of the body.” Everyone, he says, had missed Colly and Ellice at the graduation ceremony,

yet it seemed that you were there, the way the meaning of your life and what you gave dominated everything people had to say. Ours was the most miraculous meeting, some 40 years ago, and its significance has been kept alive even by people we do not know. I am grateful and happy that it has been so.

The hoped-for next meeting never materialised. Collymore died five months after that letter.

•

Collymore’s assistance to Derek Walcott at the beginning of Walcott’s career has something of the quality of legend about it. On 17 January, 1949, Harold Simmons of St Lucia, who had been in animated correspondence with Collymore for about three years about the emerging West Indian literature, writes enthusiastically to Collymore to tell him that Derek Walcott is sending him directly an autographed copy of his 25 Poems, which had appeared that very day. He says that he looks forward anxiously to Collymore’s comments, and adds: “Derek will be 19 on January 23rd — it is almost unbelievable that he is so mature — or premature in thought.” Simmons was young Walcott’s painting tutor and mentor.

By 22 January, Collymore was writing to tell Swanzy of his “important discovery”: “I do not know when I have read anything so exciting. I have written Simmons to get more information about him, and to ask him to forward you a copy if he has not already done so.” After receiving a copy of the book, Swanzy was as excited as Collymore about the find. A substantial selection of Walcott’s poems was soon read on Caribbean Voices and Swanzy soon arranged for a review by the English poet Roy Fuller. In March, Collymore gave a talk, “An Introduction to the Poetry of Derek Walcott”, to a Bridgetown literary society, with substantial extracts from the poems being read by Alan Steward, a British Council officer in Barbados. This was the first lecture ever given on Walcott. It was published in Bim No. 10 (June 1949). That number also included the first of many Walcott poems to appear in the magazine.

Soon Collymore was seeing to the publication in Barbados of a second edition of 25 Poems, then Epitaph for the Young (1949) and the verse drama Henri Christophe (1950). Collymore’s correspondents write asking for copies of the various books: for example, Cecil Herbert, the poet, and Albert Gomes, in September 1949, with regard to Epitaph for the Young, and Herbert again in 1950, regarding Henri Christophe. This correspondence shows how much of a hub Collymore had become for the little, scattered circle of persons caught up in the emergence of the new literature.

In April 1950, Errol Hill, then studying at London’s Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, writes: “I spent an afternoon with Edgar [Mittelholzer] two weeks ago and we discussed old times and new thoughts and particularly West Indian literature, drama and Bim.” He asks to be put on Bim’s subscription list, asks for a copy of Walcott’s Epitaph, asks if Christophe has been published yet, and, if so, could he have a copy. He asks if Collymore knows whether Walcott would “give [him] the honour of producing it in Trinidad . . . by the Whitehall Players.” Then he says, “As you seem to be the force round which most of our literary efforts revolve, I should be grateful if you would keep me supplied with any fresh literary creations and especially plays.”

In May 1949, in response to a query from Swanzy as to Walcott’s colour, Collymore explains that he has never met Walcott, but hazards a reasonable and cautious answer on the basis of Simmons’s charcoal sketch, of which he sends Swanzy a proof copy. Collymore and Walcott first met when the latter spent two week in Barbados in August and September 1949. He stayed with the Collymores for the first week. Frank reported to Swanzy (29 August, 1949):

He is a charming, sensitive, and very likeable boy; reserved almost to the point of shyness, and completely unspoilt. I do not know when I have met a youngster who impressed me so much.

On returning home, Walcott wrote back in delightedly whimsical appreciation of the Collymore hospitality. In earlier letters, he had written with unstinting gratitude for all that Collymore was doing on his behalf, and with interest in Collymore’s own writing as well as his acting. Walcott’s generous recognition of other West Indian poets of the time is noteworthy:

But I would hate to be made an important figure at nineteen. I have no desire to light a beacon that has been burning with a certain steadiness before in the work of Campbell, Collymore, and Seymour and which Telemaque and Lamming et al are all contributing to.

Many years later, Walcott told Edward Hirsch: “Frank Collymore was an absolute saint . . . I’ll never forget the whole experience of going over to Barbados [in 1949] and meeting him.”

For twenty years, Walcott regularly contributed poems to Bim, some twenty-nine in all, from the awkwardly precocious “A Way to Live” (No. 10, June 1949), not so far collected, to the highly regarded “Landfall, Grenada” (No. 48, January–June 1969). Like the latter, other distinguished pieces also made their first appearance in Bim, including the path-finding sonnet sequence “Tales of the Islands”. Also appearing alongside “Landfall, Grenada” in No. 48 was a love lyric titled “The Lake”, which was to prove the first published version of the second stanza of section two of chapter fourteen of Walcott’s verse autobiography Another Life.

Walcott was in New York City at the end of 1958, when he “read on a grey afternoon . . . in a taxi, ‘Bim will cease publication . . .’” In response to this catastrophic news, he dashed off a fairly long, emotional letter to the editor of the Trinidad Guardian. It was published on page six of the edition of 7 January, 1959, by wonderful coincidence Colly’s birthday. In it Walcott said, among other things:

It is like reading of the death of Frank Collymore, the kindest and gentlest person I have ever known, for the dying of those numerous voices of our little literature is to close a part of “Colly’s” heart . . . Where will the younger writers be read now? Bim will cease publication . . . Who can imagine Colly with his tousled white head, looking like a browner version of Yeats in a high wind, not bending over bad manuscripts, occasional good stories and several good poems, groaning and grinning.

In “The Story of Bim,” Collmore wrote that he would “never forget” that letter. Happily, Bim got a stay of execution.

•

The last letter I received from Colly was written in July 1979. His handwriting had become a near-illegible scrawl. He was 86, suffering various ailments, his eyesight was very bad, and writing was hard. He told me that he had been knocked out by a virus recently. He asked if I thought he should publish a new selection of his poems, and if I had seen any of the poems of Lennox Honychurch (his wife’s nephew). He had been “impressed by some of them, which [he] had hoped to get for Bim.” Then, just before his closing greetings for my wife and daughters, he ended, “Do send things for Bim, either in c/o yrs truly or,” and then he gives John Wickham’s address. He was eighty-six. He had stopped seeing to Bim six years earlier. He was to die exactly one year later. But that was Frank Collymore, always thinking ahead about Bim and West Indian Literature.

•

Adapted from Edward Baugh’s forthcoming book on Collymore.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, May 2008

Edward Baugh is emeritus professor of English at the University of the West Indies, Mona. His poems have appeared in numerous journals and anthologies, and his second collection, It Was the Singing, appeared in 2000. He recently published a book-length study of Derek Walcott.