Shades of history

By F.S.J. Ledgister

A Black Soldier’s Story: The Narrative of Ricardo Batrell and the Cuban War of Independence, ed. and trans. Mark A. Sanders

(University of Minnesota Press, ISBN 978-0-8166-5009-5, 288 pp)

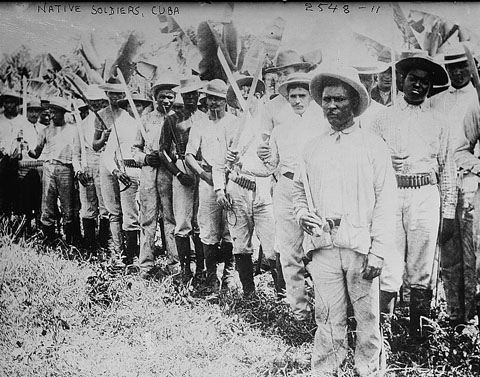

“Native Soldiers, Cuba”, c. 1910–1915, from glass negative; Bain News Service image, George Grantham Bain Collection. Posted at Flickr by the Library of Congress

Cuba’s fight for independence in the nineteenth century is a story not as well known as it should be in the Anglophone Caribbean, and one overshadowed by the much better known Revolution of 1959. The names of the heroes of Cuba’s independence struggle — Carlos María de Céspedes, Máximo Gómez, José Martí, Antonio Maceo, Mariana Grajales — have, with perhaps the exception of Martí and Maceo, little resonance for West Indians. Yet Cuba is as Caribbean a land as ours, and it gained its freedom the hard way.

Cuba also had to confront the issue of racial justice head on from the beginning. The struggle for Cuban independence was fought by black Cubans from the start — Céspedes’s and Maceo’s mambises (freedom fighters) in the Ten Years’ War in the 1860s and 70s were mostly Cubans of colour, as were those who fought with José Maceo and Calixto García in the Guerra Chiquita of 1879 to 1880. But the intervention of the Americans in the War of Independence (1895–1898), and the subsequent history of Cuba as a country established on terms dictated by the white supremacist United States at the beginning of the twentieth century, meant that black Cubans were consigned to second- or third-class status or invisibility. Black Cuban culture, the cornerstone and foundation of Cuba’s truly Afro-Latin culture, was for a long time presented to the world only by white Cubans.

A Black Soldier’s Story brings out of the shadows and makes available to an English-speaking audience the story of Ricardo Batrell Oviedo, an autodidact Cuban freedom fighter of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, who has a remarkable tale to tell about the battle for his country’s freedom and the role that Cubans of African descent played in it. But it is also a tale about how they were betrayed and shoved to the side once the War of Independence was over.

As editor and translator Mark A. Sanders tells us, Batrell was a remarkable figure, who not only rose to the rank of junior officer in the rebel army in the western province of Matanzas while still in his teens, but after the war, while not yet twenty, taught himself to read and write. The text we have is a deliberately crafted work, Para la historia (“For History”), published by Batrell in 1912, in the wake of an abortive revolt by black Cubans who had been denied full political rights in what was supposed to be a democracy, but which — since it was in reality a puppet regime of the white supremacist United States — was increasingly racially unequal. This was a period, after all, when the United States supported the suppression of one of the two black-ruled states in the Americas, the Miskito Kingdom in Central America, and turned the other, the Republic of Haiti, into a protectorate.

Batrell’s purpose in writing his account was to emphasise the role played by black Cubans in the War of Independence, and how shabbily and undemocratically they were treated subsequently. What he gives us is a dramatic story of men, almost all of them black, mostly young — he became a mambí at fifteen — armed with Remington and Mauser rifles and with machetes (the last most likely to put fear into their Spanish enemies), who showed uncommon courage during the three years of the War of Independence.

Batrell’s narrative of the war in Matanzas shows that black men fought harder for Cuban freedom than whites, and then were shoved aside in the aftermath and relegated to inferior status. That was a condition he regarded as unjust. On the other hand, for a brief moment true racial democracy appeared to have been achieved when the Spanish withdrew from Cuba: “It was in those days that there was truly a Cuban community. There were no worries or any races. Everyone was joyful and full of brotherly love.” (There is not much brotherly love for the Spaniards, the “sons of Pelayo” as Batrell calls them, with his autodidact’s love for stock epithets; or for the Cuban guerrillas who fought on their side. Nor is there much love for the majás, the Cubans, mostly white, who supported independence but did most of their fighting after the American intervention in 1898 had guaranteed Spain’s defeat.)

It is very much Batrell’s story, the account of a young man who rode into action eager to free his country and, in the process, change his own status. The ingratitude of white Cubans for the courage of black Cubans is a crucial theme. After one victory, ammunition seized from the Spaniards is taken from the black regiment in which Batrell served by the white general Avelino Rosa, commanding the Cuban forces in Matanzas, precisely because they were black, and given to a regiment commanded by a white officer. “Indeed,” writes Batrell, “there was no other reason that could explain why he unjustly took the munitions from us, except his racial prejudice.”

It would have been patriotic justice to have left us all those armaments. Because it is well known that for a veteran force like ours there is no greater restorative medicine in war than to arrive in your region with a supply of ammunition. It elevates the spirit with the anticipation of punishing the enemy and making them respect us. In this way, Rosa’s betrayal weakened us.

Similarly, at the war’s end, he declares “it became necessary to ignore or to obscure the heroism and valour of those with dark skins,” which was “a hard lesson” in liberty and democracy for black Cubans.

Sanders, a professor of African American studies and English at Emory University, provides a valuable framework within which to understand Batrell’s account, including a map of Matanzas province and part of Havana province where the events of the memoir take place. It might have been more helpful if he had said something about late nineteenth-century Cuban understandings of race, rather than simply using twenty-first-century North American racial definitions. (Antonio and José Maceo, for example, were seen not as black but as mulatto, and while that might not be meaningful to an African American scholar today, it certainly was to both a black and a white Cuban in the nineteenth century, as a marker of status.)

By finding and translating Batrell’s memoir, Sanders has performed a major service. He provides us with a direct testimonial to a piece of Caribbean history hitherto obscure and unknown to anyone not a specialist in Cuban history. Cuba’s image to the outside world as a white rather than Afro-Latin country is constantly in need of correction. A Black Soldier’s Story is an important work that shows how Cuba has more in common with the black Caribbean than with lighter-coloured mainland Latin America.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, January 2011

F.S.J. Ledgister is a British-born Jamaican. He teaches political science at Clark Atlanta University in Georgia, and has published work on Caribbean political development and political thought.