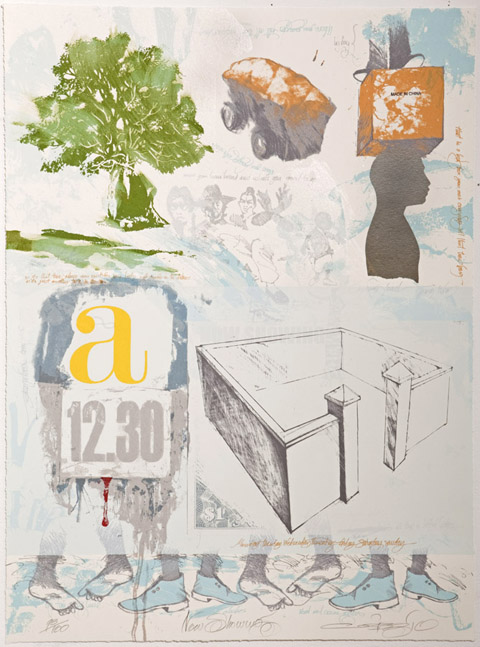

Now Showing (2010), silkscreen on paper, 20 x 27 inches, edition of one hundred signed and numbered prints, by Christopher Cozier. Image courtesy the artist and the trinidad+tobago film festival

The camera, as it were, hovers gently in the air, looking down into an empty walled enclosure. A man walks past, glimpsed only in silhouette. On his head he carries a box labelled “Made in China”, and atop that are balanced the expensive shoes and well-tailored trousers of a businessman or politician. Another strange object appears, a loaf of bread on wheels. The ghost image of a tree looms in the distance, and at the bottom of the frame a line of feet stamp out a rhythmic tattoo. Faces scroll by, some anonymous, some familiar from old movies: Clint Eastwood in a Stetson, a Zanjeer-era Amitabh Bachchan, Jimmy Wang Yu in character as Fang Gang the One-Armed Swordsman. And a block of text that might be the corner of a tattered marquee poster, announcing “12.30”. Showtime? Headline? Deadline?

•

Like a complicated multiple-exposure shot in an old avant-garde film, Christopher Cozier’s Now Showing conjures up an atmosphere of both nostalgia and sinister comedy. The eye doesn’t know where to focus first. The imagery derives from the artist’s private vocabulary — as he explains in a series of notes — but refers to a familiar gritty urban Caribbean space you could call Kingston or Georgetown or Nassau, though in this case the specific location is Port of Spain.

In his sardonic late-70s poem “The Spoiler’s Return”, Derek Walcott imagined the shade of the calypsonian on leave from Hades — “I decompose, but I composing still” — gazing down from the heights of Laventille across his former hometown. Through the eyes of his narrator, Walcott builds up an almost cinematic portrait of the city. Spoiler remarks:

all Port of Spain is a twelve-thirty show,

some playing Kojak, some Fidel Castro . . .

(A few years later, in Midsummer, Walcott fleshed out a similar mise-en-scène —

This Spanish port, piratical in diverseness,

with its one-eyed lighthouse, this damned sea of noise,

this ochre harbour, mantled by its own scum . . .

— as though writing directions for a hypothetical set designer.)

Now Showing similarly describes a world that is not a stage but a series of close-ups and long shots, where every man or woman on the street has a starring role, iPod headphones or the speakers of a passing car contribute a soundtrack, and individual fantasy and ambition determine genre: The Fast and the Furious here, Sex and the City there, Bollywood or Blaxploitation, Nouvelle Vague or mumblecore, space opera or Hong Kong kickup.

“It’s not a new question, this collision of art and life,” Cozier writes, and the Trinidadian fascination with the cinematic — with a notion of life lived large under floodlights — has often been documented and discussed. V.S. Naipaul, with unconcealed irritation, described it as long ago as 1962, in The Middle Passage:

In its stars the Trinidad audience looks for a special quality of style. John Garfield has this style; so did Bogart. When Bogart, without turning, coolly rebuked a pawing Lauren Bacall, “You’re breathin’ down mah neck,” Trinidad adopted him as its own. “That is man!” the audience cried. Admiring shrieks of “Aye-aye-aye!” greeted Garfield’s statement in Dust Be My Destiny: “What am I gonna do? What I always do. Run.” “From now on I am like John Garfield in Dust Be My Destiny,” a prisoner once said in court, and made the front page of the evening paper.

For Naipaul, this taste for “the Hollywood formula” (or for “Indian films of Hollywood badness”) was evidence of Trinidad’s “fraudulent” cosmopolitanism. “Trinidadians of all races and classes are remaking themselves in the image of the Hollywood B-man,” he wrote. But forty years later, in Reading & Writing — older, less anxious, with less to prove — Naipaul admitted his own debt to the popular cinema fare of his childhood:

Nearly all my imaginative life was in the cinema. Everything there was far away, but at the same time everything in that curious operatic world was accessible. It was a truly universal art. I don’t think I overstate when I say that without the Hollywood of the 1930s and 1940s I would have been spiritually quite destitute.

To observers of a certain bent, this is all evidence of the infiltration of foreign cultural influences: the short, slippery path from gangster movies and rap music to a voracious murder rate. But the first movie theatre opened in Port of Spain in 1911. Larger-than-life moving images of elsewhere have been part of our urban landscape and our collective imagination for nearly a century, at once feeding upon and stimulating an even older proclivity for self-dramatisation, a role-playing mode of being instantly recognisable as a quintessential Trinidadian trait. We play ourselves, make style, gallery, exantay. The mind’s camera rolls.

•

But within the frame of Now Showing, who plays the lead? Fragments of handwritten text, like lines detached from a script, float over and around the images. The most revealing may be a simple recitation of the names of the days of the week: “Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday.” Because what the lens of the artist’s imagination brings into focus are precisely the details of the mundane — a concrete wall, a tree, a pair of feet walking past, shod in trendy Clarks boots — that give emotional texture to the movie of our everyday lives. (“The Life Movie”, as the Jamaican poet Anthony McNeill put it.) Now Showing hints at numerous narratives — personal, public, comic, tragic — unreeling simultaneously. But the key story is about how unassuming moments or gestures can become motifs or symbols or icons when they are observed and recorded — by a camera, a pencil, a pen.

The cut-tree (cut-nature) is, of course, the one outside the Forensic Centre in Federation Park. I have been looking at it for some years now — and especially so since the rise in daily murders in our city. I find it interesting that the tree was cut down, the trunk burnt out, yet it’s sprouting again. To me this says something about history — about persistence and

hope . . .Often I am driving past this location. The people standing around [the tree] may have lost a son, a father, a brother or relative, for example. While waiting, they are hearing gunfire from the police shooting range over the wall.

You can push the conceit too far. Life is not art. The guns shoot real bullets, and nobody has a stunt double. But we can’t live without remembering and imagining, and memory and imagination borrow forms and shapes from the alternative worlds created by artists. In other times and places, we might have understood moments of our lives as scenes from a play, chapters in a novel. Now we understand ourselves in a different and accelerated medium: we live in movies, music videos, video games. The images flash by faster and faster. What do we see when we freeze the frame?

•••

Some of Cozier’s preliminary sketches and source material for Now Showing, displayed at the launch of the print on 16 July, 2010. Photograph courtesy Richard Rawlins

Now Showing is a silkscreen edition limited to one hundred signed and numbered prints. It was commissioned by the trinidad+tobago film festival as the official 2010 festival image, and created in collaboration with master printer Luther Davis of Axelle Editions, New York. Elements of the work will appear on the festival poster and other merchandise.

The launch of Now Showing on 16 July, 2010, is covered in issue 13 of Draconian Switch. Filmmaker Mariel Brown has made a short documentary about the creation of the work.

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

“The first movie theatre opened in Port of Spain in 1911.”

Now, just who was born in P-o-S in 1911?