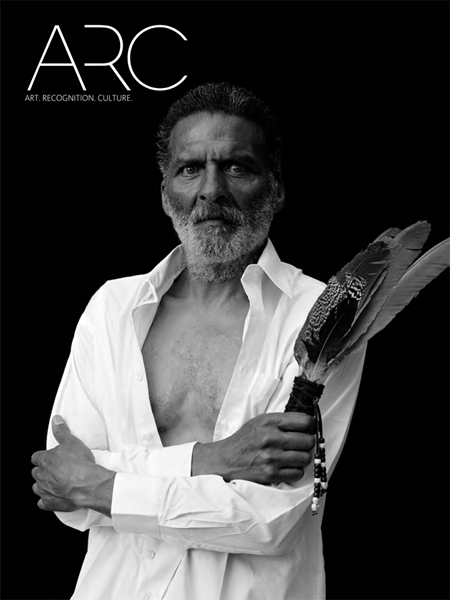

Cover of the first issue of ARC; image courtesy the publishers

Creative work can’t thrive in isolation. Every artist, writer, musician, performer, or filmmaker needs contact with creative peers, a creative tradition, and an attentive audience, but also access to a critical space, a forum for sharing and discussing ideas. To put it more simply, an artist needs not only working time and the tools of her craft, but venues in which her work can be encountered, documented, and evaluated: galleries and museums, catalogues and magazines. For Caribbean visual artists, the latter are in short supply. In the Anglophone Caribbean particularly, visual art publications produced to international standards are rare.

ARC is a bold and brave intervention into this circumstance. Published by two young artists from St Vincent and the Grenadines, ARC defines itself as “a Caribbean art and culture magazine dedicated to highlighting emerging and established artists.” Holly Bynoe, ARC’s editor in chief, and Nadia Huggins, the magazine’s creative director, both work in the medium of photography. ARC is an ambitious extension of their creative practice, and a decisive engagement with the work of their contemporaries in the Caribbean and its diasporas.

The magazine’s website went live this week, and the first quarterly print edition of ARC will be launched later this month (find out how you can get a copy here). It features work by the Jamaican photographer Radcliffe Roye, the British filmmaker (with St Lucian roots) Isaac Julien, and the young Barbadian Sheena Rose, among other artists. Via email, Bynoe and Huggins answered a few questions about the project’s inspiration and intent.

Nicholas Laughlin: ARC is an acronym (“Art. Recognition. Culture”), but it also suggests, among other things, the geographical arc of the Antilles and the sense of a creative trajectory. What else?

Holly Bynoe: ARC, to me, informs and starts to discuss a projected motion — up, out, and beyond — into a space and a place of curiosity, where some things are defined and structured, and others are akin to the human condition — i.e., existing in an unsure and ambiguous space. ARC attempts to record and take stock of the individual processes that allow for creativity.

It is a play off the archipelago; one of the first shapes embedded in our collective unconscious, and the shape of the “first recorded boat” and the last boat my father worked on. In many ways, the word and its shift are deeply personal and related to my history. I think it is funny that the two mirror each other, especially when we consider the waters, boundaries, and motions of people across the region, and the way we have come to know each other through our similar experiences informed by this movement — their geographic dispersal and how this shape in many ways references a starting point, but never a final destination. And the lack of a destination or a defined position when considering a container or a contained space for art brings up wild ideas about form, structure, directions, and narratives.

Nadia Huggins: I really wanted a name that could roll off the tongue easily. A word that would be indelible in people’s minds. I’ve had a few people refer to it as “The Ark.” I find this really interesting, given the sort of history we come from. I love the way people make their own connections with the word: Arc, Arch, Ark, Art. The play on the archipelago is a really important aspect — I feel as though we are running a common thread through all of the islands and pulling each other closer.

From a visual standpoint, I wanted the name to have impact. The first element to a successful masthead is your name. Once the name functions in speech, it can then be translated into design and have varying effects. The letters function very symmetrically; there is something about a connection between the letters, each flowing seamlessly into the others, the same way a curve functions. Regarding the acronym, the letter R is the most important, because I wanted to give young artists the opportunity to be recognised for their work. If you dissect the logo, the R has a unique personality to it, whereas the other letters stand at an end. It is about creating that connection.

NL: What was the spark of inspiration or provocation that made you decide to start the magazine, and how does it fit into the continuum of your respective creative practices?

HB: Nadia and I have been discussing the possibility of working on something of ours for a long time. With our backgrounds in photography and our versatile growth over the past three years, it seemed a ripe time to consider it. I turned thirty, finished my MFA, and lost my father in the space of a week. I think when you go through such drastic shifts and change, you come out of it understanding what risks are, and above all what is important. It was time for me to figure out how I was going to fulfill that urge to create and be a part of something that would have a collective and necessary impact on my social space and geography.

I have an intensive photographic background, and I have been thinking about images — their culture, format, composition, history, and their interaction within spaces, be they formal, dictated, or arbitrary — for a good part of seven years, the last three with a strict academic focus. Being involved in a project like ARC forces me to first engage myself with dialogues and mediums that begin as being peripheral, only to realise that we all share a common “language” and code when we create. I have been looking at the work coming out of the region, and I think it can only benefit my personal practice.

I am interested in opening a space and discussion about how contemporary photographic practices are changing in the region. I want to find artists who are involving themselves in a global dialogue while remaining true to the dynamism and context of their lived experience.

NH: Honestly, I was feeling stifled with the commercial work I was creating. I felt as though I didn’t have an outlet to do the things I enjoyed most. I wanted a design project to explore type and images and to pour all of my meticulousness into — hence ARC. I also really love sharing information and ideas with people. I don’t think there is enough exposure given to what is going on around the region. I spend a lot of time on the Internet exploring and exposing myself to as much as possible. It has opened up my mind immensely.

I never had the opportunity to expand my horizons by going to college or travelling, so the Internet has always been my teacher. I think there are a lot of artists out there without this opportunity as well, who aren’t sure where to find the right kind of information to help them grow. Artists want to know what other artists in the region are doing. They want to explore and compare each other’s process and outcome. I wanted to create a central space for them to explore other people’s creations, ideas, and struggles. Exposure is crucial to growth.

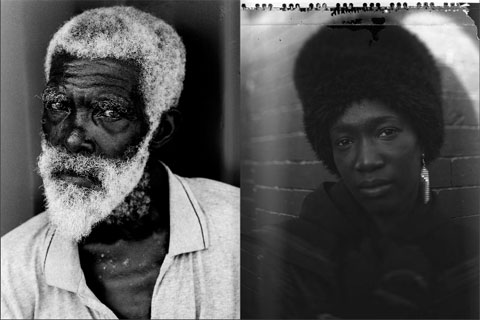

Spread from the first issue of ARC, featuring photography by Radcliffe Roye; image courtesy the publishers

NL: What are ARC’s defining characteristics, and how do you imagine it fitting into the wider context of critical attention to visual art in the Caribbean?

HB: I see ARC as a playground, a space for experimentation and the unlikely. Our definition will ring through by the fact that we pay a great deal of attention to our artists and writers, their individual concerns and thoughts about reproduction, structure, and presentation of work. We don’t presume that ARC will fill a space in every artist’s household, but we want it to become a part of the way people come to understand how creativity is no longer a contained or static force. Everything is affected by it, from the way we communicate to the way we expose and represent ourselves to each other; one look at Facebook and you can see the way photography has changed how we understand the world around us. It is now a ubiquitous medium.

I also want ARC to enforce the fact that the artist is no longer a strictly autonomous or insular being. I want to have ARC interact with the culture of individuals and have them come to understand why it is important to start having a discourse set up around supporting and harnessing the potential of art. I don’t see its space as solely critical. While I think it is important to have fully fleshed out studies and explorations, I also think the way we are going to separate ourselves is to treat its presentation like an art piece, keeping in mind the way we all subjectively interpret and come to understand ideas, concepts, and visuals that relate, contradict, or support each other.

We are hoping to engage and enable the current generation of emerging artists who are formulating new ways of presenting themselves. Most of them are unsure about what they are creating and are working with process, spontaneity, and modernity in a visceral and reactive way. There are a lot of risks being taken now, and we want to explore how seasoned artists are in discourse with the emerging creators.

NH: When I first envisioned the magazine, I felt we had to ensure the design was clean, classic, and sleek. What we’ve done with the design isn’t unique, but I think it meets a certain standard in the way art magazines are done. I dislike publications where you feel as though you are being bombarded with information and you are unable to absorb what is necessary. There’s already a circus going on in an artist’s head, why overwhelm them with more clutter? I think there needs to be a rhythm and space to breathe when browsing pages. There is a reason why you go into a gallery and there are white walls — this is so you can focus on the central elements in the space. In our case it’s the text and images. That was one of the most important factors to me, creating and maintaining a particular aesthetic.

Also, I envision ARC as a place to exchange ideas. One of the most important things is to have that interaction; we want people to give feedback on the work that is being presented and share their ideas and frustrations too.

We also want to use the space to educate artists, which is why we are incorporating tutorials and tips on different processes, especially of how to move forward in promoting and cataloguing their work. I think a lot of people underestimate the power of the Internet, and they don’t have a handle on how it works and how it can improve your craft. That is why a lot of places like deviantART and Behance succeed in helping artists — there is a lot of interaction between the artists and their peers. I think this is crucial in moving forward. Artists need constructive criticism and positive feedback to improve. It’s time for us to start supporting each other.

NL: What’s been the most surprising discovery in the process of founding and launching the magazine?

NH: The demand for a publication of this nature is what surprised me the most. People are really excited about the project, because they want to have an uncensored space to see work, and have their work be seen. I get complaints that most of the spaces available to artists are pretentious and cater to only certain types of work. I believe it’s mainly the younger artists who share this sentiment — they feel excluded and they are intimidated by the current system’s set-up. This is why they gravitate to a lot of international spaces. There is that anonymity and that feeling of acceptance and open-mindedness. You have to be producing a certain type of work and moving within a certain circle of artists, you have to learn to speak a certain way.

I understand the importance of presenting yourself as an artist in a certain way, but I don’t think this approach gets through to the younger artists. They are not interested in this way of doing things. They like to think of themselves as rebellious and progressive, and they want a space like that where they can express themselves without feeling judged. There are a lot of stifled young people and artists in the Caribbean; we want to provide a space for them.

I want to help in the process of breaking down these walls in the region. I want our artists to be fearless when approaching us, regardless of the content of their artwork, but still maintain a high standard in the quality of work presented.

HB: I am most surprised by how amorphous ARC is. Even in its becoming, it changes every day. In this very premature stage we are coming to terms with how little we know. The learning curve gets steeper and we push on to create a space for it in order to honour its intention and merit. I think ambition and resources often clash. We have had a lot of support from our various networks and families. Without that, ARC would still be an idea.

The importance of envisioning your dreams can’t be overstated. When we started thinking about the project, it was in a neat container. Now it is free, without a lot of ideological judgments. I am not so naïve as to say we don’t have a purpose or agenda. The more we interact and show people what we are doing, new ideas, thoughts, and information materialise. We are very receptive to voices that we trust and we both have an intuitive sense of where we want this to be a in a couple years.

I am also very shy and self-conscious, and I have realised that through ARC my shame has sort of diminished. Even though it is still hard for me to fill roles that I am unsure of, every day I gain a little confidence. Pace is the trick. ARC is a full-time job for five people. I am still getting used to its dynamic, orders, and language.