“I live a simple life”

Pedro Juan Gutiérrez talks to Nazma Muller about writing, poverty, and the dangers of autobiography

Cuban Pedro Juan Gutiérrez is best known for the cult classic Dirty Havana Trilogy, a steamy, sex-soaked series of short stories about the hell Havana became in the early 1990s, when the Soviet Union stopped giving aid to the Cuban government. Unabashedly autobiographical, the book chronicles Gutiérrez’s desperate, promiscuous efforts to stay sane as his marriage and the economy collapse. Although banned in Cuba, Dirty Havana Trilogy has been published in twenty countries. In addition to his other books set in Havana — Tropical Animal, The Insatiable Spiderman, The King of Havana, and Dog Meat — Gutierrez has published seven works of fiction and eight books of poetry. He continues to live and write in his home city. Earlier this year, after much sleuth work, Nazma Muller tracked him down in his infamous penthouse apartment overlooking the Malecón. This conversation was originally conducted in Spanish.

•

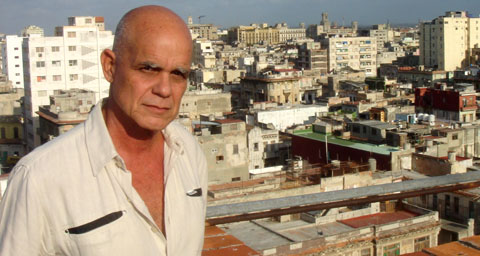

Pedro Juan Gutiérrez. Photo by Nazma Muller

Nazma Muller: Señor, the Cuba you describe in the Trilogy has changed a lot. Visitors today would find it difficult to believe it’s the same place you described in Dirty Havana Trilogy.

Pedro Juan Gutiérrez: What tourists see is very different from the reality. They see only the beautiful parts. They don’t go into the interior, inside the barrios. I went to a literary festival in Cartagena de la India in Colombia. It was beautiful, historic and clean, police on every street corner. And then a Colombian writer who grew up there told me, this is for the tourists. If you go to other parts, it is very dangerous.

Havana is like any other city. If you go into the interior, in the side streets, far from where the tourists visit, you will find the Havana I describe still there. In Tropical Animal, I present a deeper Havana, more intimate, more real. I write about Havana on the ground, the cockroaches, everything.

The King of Havana is about a beggar, a young man. He is only fourteen years old. He is alone. He has no family, no brothers, no sisters. And he starts to roam the streets. The whole novel is in the streets. He has nothing, only un gran aparato [a big dick]. He lives by this. There are boys like him in every city — in Cartagena, in Rio de Janeiro . . .

NM: Where did you find the courage to write books like Dirty Havana Trilogy? I’m not talking about the politics. In the books you are naked, literally — exposed. You bare your soul.

PJG: In the first place, I had been writing since I was eighteen, nineteen. Short stories, poems, songs — but in secret. Everyone knew me as a journalist, not a writer. Since I was forty-four years old, I have lived in this place, this apartment. I had a huge crisis. I had just got divorced from the mother of my two children. It was a difficult divorce, badly managed by both of us. I was in total crisis — ideological, personal, economic. The Revolution was bad for me too: everything that I had believed in didn’t materialise. The economic crisis was brutal. As a journalist, I earned enough money every month to buy thirty eggs, that’s it. And then there were no eggs. I had three hundred pesos in my hand, but there was no food to buy. There was no fuel for the garbage trucks. Rubbish piled up in the streets. What to do? Commit suicide? Drown myself? Hang myself? Go mad? Leave the country? I was thinking, I couldn’t live in Cuba permanently. Maybe I could go to Europe for three, four, five months. But in that moment I couldn’t go.

This is the typical response of a desperate person: alcohol, sex, cigarettes. I smoked a lot. This apartment had nothing. No TV, no music, only a box with two blocks, and there I stayed. Nothing, nothing. There was nothing to do. It was very depressing. I think all the women of the Malecón passed through this apartment because they had nothing else to do. One day I met a Spanish woman on the Malecón. We went to Spain. I spent two months there, but living in Spain didn’t interest me. I returned.

The economic crisis reached its peak in 1994. In September of 1994, I began writing Dirty Havana Trilogy. It is autobiographical, excessively so. There was nothing to do but drink rum and smoke. It was very bad. There was nothing to eat. When you got a little money, you bought some bad rum, cigarettes. We suffered a lot. To stop myself from going insane, I began to write.

Pedro Juan in my books is a typical Cuban man — macho, alcoholic, sexual. You must remember that the literary tradition in Cuba was very cultured, with writers such as José Lezama Lima seen as the great icons. I broke that tradition.

After writing Dirty Havana Trilogy, Tropical Animal, and The King of Havana, I went to Spain and Italy to promote them. When I came back, I lost my job as a journalist. I was told my services were no longer required. Journalism in Cuba is very controlled and manipulated, excessively so.

I had written a lot. Now, I am trying to take it easy. In twelve years, from 1994, I have written ten books of prose and four books of poetry. I am thinking of writing about St Francis of Assisi.

NM: But after writing all these books about sex, you don’t think your readers expect more sex?

PJG: It’s a problem all writers have. But that doesn’t interest me anymore. I wrote about certain people living in a specific time and situation. To write about oneself is masochistic, because you live the experience again. All the pain and emotions, you feel them again. The book I am working on now is antituristico — an anti-tourist guide [Corazon Mestizo, published in June 2007], where I travel around Cuba, visiting the towns that tourists don’t go to. It doesn’t mention Varadero or the Tropicana cabaret. It goes into the barrios and meets the people who live there — artists, transvestites, workers — explores their sexual lives, over rum, music, and cigarillos. It’s very interesting.

I also have ideas for books on Cubans living in Spain and other metropolises. The ordinary immigrant Cuban, his life. These are the ideas I have for books. I don’t write to make money, thinking about what the reader will want, wondering if there is enough sex in the book. What is important to me is my freedom. In Spain, I needed 2,500 euros a month. In Cuba it’s much cheaper to live. And I live a very simple life. That to me is my freedom. To write what I want to write.

NM: What has happened to your friends, the characters in your books — are they still struggling, are the prostitutes still hustling?

PJG: [pauses] Poverty is circular, difficult to escape. That doesn’t change. The protagonists of my books are not these personalities, or Havana. I don’t think so. I think it is poverty. The psychology, the culture, it repeats itself because there is no hope. So, it will take a long time to break that circle. It will take a generation to break that cycle. But slowly things are getting better for them. Some have family in the US who send money. But there are those who have no family, no help. I am not optimistic for them.

NM: There is poverty all over the world, but there are opportunities for the poor to change their circumstances. I like Cuba a lot but it seems that there is nothing here that can improve the economy.

PJG: We don’t have many natural resources. In Cuba the only natural resource is tourism — the beaches. We have sugar, but the situation with sugar is complicated. We have eleven million people, a lot of people. So, I write, I paint, and I leave it to others to find the solution. I try not to get involved in politics because I think literature should be free of politics.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, November 2007

Nazma Muller is a Trinidadian writer and journalist who has worked in Jamaica and the UK, and written on everything from wining with the Reggae Boyz to stalking Fidel Castro.