Literature from where I stand, or rather sit; no, make that stand . . .

Kei Miller on being, or not being, a slam poet

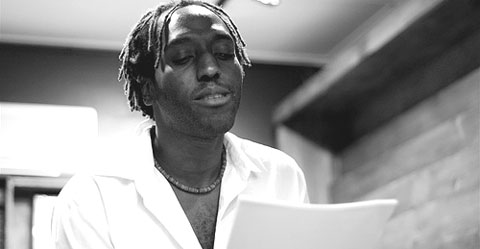

Kei Miller. Photograph by Georgia Popplewell/Caribbean Free Photo

Probably most of us — writers here at the IWP* — have won some literary award we’re rather pleased about; were you to ask about it, we would tell you the story of our accomplishment with that strange mix of pride and dismissal, like the woman complimented on her newly bought outfit. “Oh,” she says, “this old thing?” Today, however, I want to tell you about a prize I am actually not so proud of — a triumphant win whose triumph eroded quickly, because I wished the cameras hadn’t flashed, and that my picture hadn’t appeared in the papers the next day. It is an accomplishment that does not appear in any bio note or on any of my constructed CVs. And yet, because of what it did, it was probably the noblest literary prize I’ve ever won — it paid for heat in a week when it was cold, and it provided food in a week when I was hungry.

About three years ago I had recently arrived in Manchester, England. I arrived the way most students arrive — poor, and in my case without a scholarship or grant, and as yet without the money from the sale of my car in Jamaica. Listen now to the mechanics of a miracle: in that first penniless fortnight, I saw posters put up around the city advertising its upcoming poetry festival. A £100 prize was going to be given one Wednesday night to a lucky poet who went on stage and captured the judges’ hearts. I called immediately to book a spot, but was disappointed to find out that several people already had their greedy eyes on my £100; all the official spots were gone. I could only give them my name. They would put it in a box from which they would randomly pick and call names on the night of the competition. So only if I was lucky . . .

There was yet another complication. The event started at seven. My class on Wednesdays also started at seven. I would have to rush, arrive late, and see if I was still lucky. At best, it seemed, I would get to see the Manchester poetry scene. At 8.30, I took a bus into the city centre, consulted a map, and found my way finally to the club. Things were already wrapping up. Three of the four finalists had already been chosen. The box was empty but for one name, and as I walked in they were pulling out this last name and trying desperately to pronounce it with each vowel sound: Kay? Key? Kei?

Kei Miller. My own name. My own name had waited for me. It had dodged every finger dipping into that box. It had sat at the bottom, clung to the cardboard, and waited until the body whose presence it spoke for had arrived. I went on stage and won the competition. Cameras flashed; the next morning it was all about: Kei Miller, freshly arrived from Jamaica, was the 2004 Manchester Slam Poetry Champion.

A slam poetry champion! O Christ. If an avalanche could only have buried me then. When my professor, one of Britain’s most respected critics, congratulated me with, “Well done, Kei, I read that you won some slam thing or the other,” I knew it wasn’t a real compliment — it was a realist painter saying bravo to a child’s crayon drawings. It was a concert organist smiling benevolently at some idiot who has learned to pick out “Mary Had a Little Lamb” on the piano. I wanted to explain: Please, sir. You misunderstand. I’m not a slam poet. I don’t do slam. I swear. I only did it for the money. I’m a real poet.

I am ashamed to have won that prize, and truth be told, I am also ashamed that I am ashamed.

The debate I’m trying to re-invoke here — literature from where I stand, or sit, or stand, or sit — is a new one that is quickly becoming old: a debate over the craft of poetry as it exists in rowdy performance halls versus the craft as it still exists in solitude; a fight between the poet who does his best work standing up, who finds his greatest eloquence on stage, and the poet who does his best work sitting down, who finds his greatest eloquence on the page.

A description of the successful “page” or “sit-down” poet is, perhaps: someone who has published poems in a few major journals, who has a couple of books published by a well-respected press, who knows how to hobnob with the best of them, and is invited to give readings by the National Poetry Society of America. In all likelihood he is, like most sit-down poets, a bitch, and probably, as a day job, holds a faculty position at some stuffy five-hundred-year-old university. In other words: me.

The “stage” or “stand-up” poet, on the other hand, has probably won a couple of slams and is invited to give performances on BET. He is youngish — not yet thirty — and has funky hair. He would ideally like hip-hop and reggae, and fit into that strange demographic America has invented to describe all things non-middle-class and non-white: in other words, he would be “urban.” He is completely social — gregarious even. If he went to university at all, he didn’t finish; he dropped out at the same time the university asked him to leave, and decided then he would become a poet, ranting against the system and all kinds of oppression. In other words: me.

That these two descriptions should inhabit one body is perhaps the source of my schizophrenia, because typically I’ve learned only to embrace the first. So consider this: although I almost never need to look at a book or a printed page to recite any of my poems, I have begun to take blank sheets of paper up with me to podiums, to shuffle through and glance down occasionally at their emptiness, all to give the illusion that I am reading — to remind the audience that I am not performing, or slamming, and that literature is coming only inconveniently, at that moment, from where I stand. Really, at my essence (I’m trying to declare), I am a sit-down poet.

Knowing then my diagnosis, will you forgive my strange (albeit completely internal) reaction when a student right here in Iowa came up to me and said, “Oh my god! You’re awesome! And what I love about you is that you perform your work. It makes it so interesting!” Oh no no no no, I wanted to say. You didn’t! You didn’t just call me interesting! Hell, no! You just caught me on a bad day. You caught me on an off-morning. But see — I’m a real poet, and honey, when I’m ready, I will bore the socks right off of you. I can be your ten-hour lecture. I can be a drone. I can be that voice at the open mike who insists that every poem is different from the other, but, oh, the relentless monotone that has you slipping off to sleep every few seconds makes his sonnets sound the same as his villanelles as his haikus — makes his iambic metre sound the self-same as his anapestic skipping. Oh, child — I’m no performer. I am a poet. Get it right! And don’t you ever call me interesting again!

Isn’t it silly? Isn’t it absolutely silly the clubs we try to be a part of, and the clubs we try to be apart from? This odd way we relish the privilege of sitting at the most boring tables, negotiating carefully between the cake fork, the salad fork, and the dinner fork, pretending that the real fun isn’t happening behind us in the kitchen? Isn’t it silly this insistence that we belong to certain prestigious groups — that we be “sit-down” poets, Oxford poets, Iowa poets, published-in-the-New Yorker poets, published-by-Knopf or -Faber poets? Isn’t it silly, the way I flatly refused that performance on BET? Stupid, the way, only last week, I politely declined reading a poem on a slam stage in front of five hundred people, but relished in performing the next night to a more distinguished audience of thirty? And in refusing to be put into one box, do I not cling desperately to the inside of another? Isn’t it sad, this refusal to belong to a world that has always accepted me, that has always wanted me, and that, truth be told, I didn’t always hate? And yet now when they walk towards me with open arms, instead of just standing up and accepting the embrace, I sit down and fold my arms.

And so what, if after reading your most technically ambitious poem, they come up and tell you, Wow, you were awesome. And you feel momentarily thrilled by this compliment, until a fifteen-year-old screams a histrionic rant or a sentimental poem that rhymes love with above and then dove, and they all stand and applaud and say to her, with even more enthusiasm than they did to you, Oh my god! You rock! You’re brilliant! So what. In that place, on that night, literature is about how we stand up and give an account of who we are, and where we are in our own voices. And at another time, in another place, isn’t it enough that you know that literature is about sitting — is about more than the abundant overflow of emotions, but also its recollection in moments of tranquility?

The two things can coexist. Just as they are coexisting right now, in a strange way. Because hasn’t every road suddenly led us to that wonderful duality? If you decide that this humble offering is at all literature, then it is happening from where I stand, and from where you sit. For there you are, sitting, reading the text right along with me — and here I am, standing, giving it voice. Literature. From where you sit, from where I stand — it is happening. Or rather — it was.

•

* This essay was originally presented in a panel discussion at the University of Iowa International Writing Programme, in October 2007.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, February 2008

Kei Miller is a Jamaican poet and novelist. He lectures in creative writing at the University of Glasgow. His most recent book, There Is an Anger That Moves, was published in October 2007.