On broken ground

By F.S.J. Ledgister

Caribbean Culture: Soundings on Kamau Brathwaite, ed. Annie Paul

University of the West Indies Press, ISBN 978- 976-640-150-4, 439 pp

We are in the midst of an age of reassessment. The Centre for Caribbean Thought’s series of conferences at UWI’s Mona campus on Anglophone Caribbean thinkers like Stuart Hall, Sylvia Winter, George Lamming, and Walter Rodney mark a realisation that the region is mature enough to have ancestors in the age of decolonisation and independence.

Of the major intellectual figures who have shaped academic and cultural life in the West Indies since 1945, few have had the huge impact in as many fields as (Lawson Edward) Kamau Brathwaite — poet, historian, cultural critic, teacher, advisor to governments. Those of us who were students at Mona while he taught there count ourselves lucky to have made his acquaintance and learned from him, inside and outside the lecture-room.

It was an extraordinary experience for me to read Brathwaite’s poetry as a teenager — The Arrivants was first published as a complete collection in 1973, and I had read Rights of Passage before then — and to arrive at university a couple of years later and see and hear the man himself talking not just about history, as you’d expect of a historian, but about the meaning of culture in the context of the history of slavery, racism, and exploitation. It was even more extraordinary to see that this was something that could be debated intensely; Brathwaite’s poetry and historiography were subjects discussed at the first academic conference I attended, at Carifesta 1976 in Kingston, where I was amazed to see him sitting at the back of the lecture theatre calmly listening as his work was anatomised.

It is the measure of Brathwaite’s importance to the intellectual culture of the Anglophone Caribbean that, three decades later, he can still be the hook on which a huge weight of discourse relating to that culture can be hung. This book is a compilation of papers initially presented at the Second Conference on Caribbean Culture, dedicated to Brathwaite, in 2002. Some examine Brathwaite’s own contributions to West Indian letters, historiography, and cultural studies, and others, influenced by Brathwaite’s work, are independent investigations into Caribbean — often specifically Jamaican — history, society, and culture. It is a worthy gift to a great man.

The focus on Jamaica is not altogether surprising, given the Barbadian Brathwaite’s long association with that island — he taught at Mona, and wrote a history of eighteenth-century Jamaica, The Development of Creole Society in Jamaica, 1770–1820 (1971). It can occasionally go a little too far, as when, in a brilliant essay on the origins of the African population of Jamaica, historian Douglas Chambers describes the Trinidadian linguist Mervyn Alleyne as a “Jamaican scholar,” presumably because he, like Brathwaite, taught at Mona for many years.

There are twenty-two pieces in the collection, including the introduction by Nadi Edwards, which is both an eloquently meditative essay and a brief summary of the contents of the book. It is also odd, since the introduction should normally be written by the editor of the volume, and Edwards is not listed as the editor, just as a contributor, while the volume contains no contribution from Annie Paul, though her name is on the cover and the title page. Another oddity is the absence from the book of the keynote address by Brathwaite at the 2002 conference, to which Edwards refers in his introduction. Edwards gives us just enough of a taste to make us want to see what Brathwaite had to say beyond calling the conference a golokwati, a “meeting place,” referring to a Ghanaian market town that functioned as a meeting place for several ethnic groups.

•

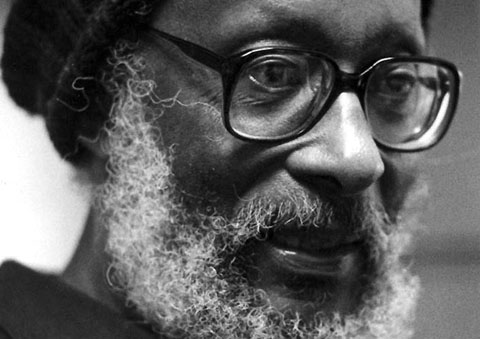

Kamau Brathwaite. Photo courtesy Salt Publishing

The first section of Caribbean Culture contains essays on language and poetry. Ghanaian poet and scholar Kofi Anyidoho provides us with a somewhat pompous appreciation of Brathwaite’s approach to the Caribbean’s African heritage from an African perspective. Maureen Warner-Lewis’s foray into Anglophone Creole poetics needs to be developed into a work of major length. Starting from Brathwaite’s History of the Voice, she manages in a very brief compass to sketch the outlines of a West Indian prosody that links the poetry of Brathwaite and Derek Walcott, Kongo chant, and calypso, among other elements. J. Edward Chamberlin presents an essay showing the similarities of colonial impact in very different parts of the Americas — the Caribbean and British Columbia — the significance of Brathwaite as a poet speaking for and to the particular experience of the Americas, and the importance of story as a means of connecting human beings to each other. Hubert Devonish examines two calypsos sung by the winner of the Pic-O-De-Crop Calypso Monarch competition in Barbados in 2001 as “examples of artistic speech acts that involve discourse about discourse.” Jeanne Christensen seeks to place Brathwaite within a tradition that “challenges the dominant orientation of Western intellectual thought,” and that seeks to recover and revive a transformative “language of myth.”

The second section connects music and poetry. Lilieth Nelson writes with warmth and eloquence about the musical elements in Brathwaite’s poetry, and it is a pity that her essay and Warner-Lewis’s are not closer together, since their themes are closely related; Nelson’s essay, like Warner-Lewis’s, deserves to be expanded into a work of greater length. Donette A. Francis discusses the influence of jazz on Brathwaite — not only on his essay “Jazz and the West Indian Novel”, but on his poetry and his personal and intellectual development as a young man growing up in the Barbados of the 1940s. And Linton Kwesi Johnson’s contribution is one that takes us away from Brathwaite. It’s a brief memoir of the Jamaican dub poet Michael Smith (1954–1983), which discusses dub poetry as a form, and tells us far more about Johnson than it does about Smith (“I did not know Mikey well enough or long enough to say that we were close, but I think that I can get away with saying we were friends”).

There are only three essays in Caribbean Culture that do not focus on the Anglophone Caribbean. In the third section, Elizabeth DeLoughrey examines the “tidalectics” (Brathwaite’s wonderfully punning term) implicit in a region where, as Walcott has it, “the sea is history” — specifically, in stories by Edwidge Danticat and Ana Lydia Vega. And Marie-José Nzengou-Tayo incisively examines Brathwaite’s Dream Haiti, noting that “the shocking experience of the Haitians has led him to question the evolution of the Caribbean region and to redefine the function of its poets and artists.”

Finally, in the book’s fourth section, we get to historiography. Brathwaite’s professional formation, after all, was as a historian, even if for much of his career he has followed other trades, and some of his most important contributions to the culture of the Caribbean have been in this field. Cecil Gutzmore’s essay manages the acrobatic feat of simultaneously praising Brathwaite’s pioneering work as a historian of Jamaican Creole society and critiquing the concept of the “Creole.” My contemporary at Mona, Glen Richards, on the other hand, sees Brathwaite as playing a central role in the creolisation of West Indian history, but quite correctly criticises him for having become excessively Afrocentric and forgetting the Asian contribution to West Indian society and culture. Ileana Rodríguez, the only Latin American contributor, discusses creolisation in the wider contexts of mestizaje, hybridity, pluralism, and transculturation, relating the Caribbean experience to broader colonial experiences, particularly the historic Latin American experience, which to Anglophone West Indians always seems so near yet so far away. In her contribution, Leah Rosenberg compares The Development of Creole Society in Jamaica with Indian historian Ranajit Guha’s essay “The Prose of Counter-Insurgency” (1981), a seminal work in subaltern studies; she notes that both writers use similar methods of “reading against the grain” in examining the colonial period, and both played foundational roles in developing a subaltern approach to history.

Next, Caribbean Culture looks at how historiography makes the past present. Verene Shepherd considers accounts of the “voices” of enslaved and indentured women in novels, historical narratives, and court records, arguing that such accounts present a universal stance of resistance to slavery and indenture, even when they’re fictional narratives written by white defenders of slavery. Douglas A. Chambers presents a very important essay on the peopling of Jamaica by the slave trade that challenges the conventional assumptions about most Jamaican slaves originating in what is now Ghana. Chambers shows that planters in eighteenth-century Jamaica — unlike their neighbours in what was to become Haiti, who preferred to import Africans from the Bight of Benin — had a distinct preference for importing slaves from the Bight of Biafra. This has, of course, profound implications for the culture and identity of Jamaicans today.

Yacine Daddi Addoun and Paul E. Lovejoy discuss a Muslim tract written in Arabic by Muhammad Kabã Saghadughu in the parish of Manchester around 1820; this is a notable addition to Islamic studies in the Caribbean, and a complement to the already well-known story of Abu-Bakr as-Siddiq. And Veront A. Satchell considers the case of Alexander Bedward and his church in late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Kingston, as a significant movement of protest and resistance to colonial rule.

The book’s sixth section examines contemporary Jamaican popular culture. Donna P. Hope takes a close look at dancehall’s misogyny, seeing what she calls “femmephobia” — a fear of feminisation — as a central element in a discourse that combines fear of predatory womanhood, incarnated as “punaany,” with adoration of the mother. Hope, it seems, has discovered that dancehall culture has enshrined the madonna/whore dichotomy in its lyrics. Rachel Moseley-Wood takes the film Dancehall Queen as her subject; she sees the film as failing to show dancehall as a subversive site of female empowerment, because it retains a patriarchal presentation of the female dancehall performer.

In the final section, Robert Carr takes a close look at the Jamaican state and the challenge posed to it by the “don system,” which has become a “subaltern state” linked both to networks of globalisation that supersede the state system and to conceptions of masculinity that exclude both women and those men who are defined as womanly or “soft.” This assessment of the state in relation to social and cultural factors, and to violations of human rights both from above and below, is the one piece in this collection that I, as a political scientist, wish I’d written. Bernard Jankee’s brief survey of Jamaica on the Internet focuses on three websites — www.jamaicans.com, www.afflictedyard.com, and www.visitjamaica.com — each very different in affect, one being aimed at Jamaicans overseas, one being the product of a Jamaican who is also a significant figure in Jamaican cultural production (but which “is not a very welcoming site”), and the last being focused on tourism.

Kamau Brathwaite might not want to take credit or blame for these essays, but his inspiration is clear in many of them. The authors do more than perfunctorily express their gratitude to him: they are engaged in profound scholarship on ground that he has prepared, whether as poet, as historian, or as cultural critic. That this is more than mere ancestor-worship is, beyond doubt, something that he must contemplate with pleasure.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, February 2009

F.S.J. Ledgister is a British-born Jamaican. He teaches political science at Clark Atlanta University in Georgia, and has published work on Caribbean political development and political thought.