A place to stand

Nicholas Laughlin on Dhiradj Ramsamoedj’s Adjie Gilas

Dhiradj Ramsamoedj holding one of his Adjie Gilas cups. Photograph by Christopher Cozier

The object the artist holds in his hand is a simple aluminium mug, with one handle riveted on and a lipped rim. There must be tens if not hundreds of thousands of similar cups in kitchens all over Suriname, lined up on shelves, suspended from hooks. But this particular cup comes from the house of the artist’s grandparents. It is one of several dozen that his adjie, his grandmother, once rented to neighbours hosting large communal events, to serve juice to wedding guests, coffee to mourners at a wake.

On the base of the cup is a roughly painted R, the artist’s grandmother’s initial, her mark of identification. And the artist too has embellished the cup, added his own mark: a stenciled stylised portrait of his grandmother. This object is Adjie Gilas, “grandmother’s cup,” but now it also belongs to Dhiradj Ramsamoedj. At once a household utensil, a family heirloom, and a cultural artefact, the cup is transformed into an assertion of the artist’s presence, thinking, and imagination.

Another view of one of the Adjie Gilas cups. Photograph by Christopher Cozier

Adjie Gilas was both the title work and the key element of an ambitious larger project created by Ramsamoedj for Paramaribo SPAN, an exhibition of recent art by Surinamese and Dutch artists installed at various locations in Paramaribo in February 2010. On the elevated main floor of his grandparents’ modest house in Kwatta, a western neighbourhood of the city, Ramsamoedj arranged a series of objects and installations across five rooms with high ceilings and wooden floors.

Adjie Gilas installation in Ramsamoedj’s grandparents’ house. Photograph by Nicholas Laughlin

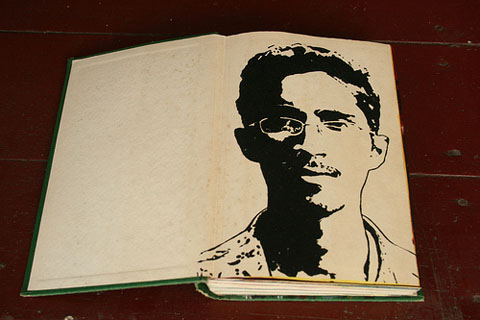

In what was once a back bedroom, dozens of the stenciled aluminium cups — many of them dinged and dented by years of use — were carefully positioned across two walls on narrow wooden shelves, forming a geometrical grid. Ramsamoedj left in situ the Hindu devotional images already hanging there, and the faded blue curtains at the open windows. In the next room, Ramsamoedj’s teenage sister kept watch over two stoutly bound books perched on a small stepladder. As visitors stepped in, she opened both books simultaneously to disclose Ramsamoedj’s self-portrait on their front flyleaves, then images painted across each page with heavy brushstrokes. These old novels, unread for years, were now Ramsamoedj’s visual journal, his dreams and anxieties replacing the text with their own narrative. The rhythm and rustle of the turning pages in the otherwise silent room, the shy smile and evident care of the artist’s young sister, lent an unexpected poignance and weight to the slowly revealed sequence of images.

Ramsamoedj’s self-portrait stenciled in an old novel. Photograph by Christopher Cozier

Flexible Man in the Adjie Gilas installation. Photograph by Nicholas Laughlin

In the main room of the house stood a life-size human figure with aspects of mannequin, monster, and Muppet. Covered with tufts of brightly coloured cloth, wearing a pair of spectacles, the figure swayed gently if nudged, but was anchored by a pair of weighted boots. Lit from below, Flexible Man threw an ominous shadow over the wall and ceiling above. Was this sculpture or costume, threatening or playful? Ramsamoedj spoke of Flexible Man and its coat of many colours as an investigation of a hybrid Caribbean identity. For a viewer from the islands to the north, it called to mind the Pitchy-Patchy character from Jamaican Junkanoo, the Pierrot Grenade from Trinidad Carnival. Like most of the works in Adjie Gilas, it also alluded to family circumstances and memory. The strips of cloth were leftover fragments from Ramsamoedj’s mother’s workshop: she is a seamstress, and his deceased grandfather was a tailor.

Installed in a family residence, with Ramsamoedj’s relatives moving through and around the space, Adjie Gilas was clearly a meditation on domesticity and tradition, ancestry and community. Just as clearly, it was a young artist’s exploration of the possibilities offered by the terrain of the immediate and the familiar. “This is Dhiradj’s active site of investigation,” wrote SPAN co-curator Christopher Cozier, “of developing personal vocabularies towards sovereign ways of articulating his own lived experiences and stories, from the inside looking out.”

Two thousand years ago the Greek scientist Archimedes is supposed to have said, “Give me a place to stand, and I will move the world.” He was speaking of the principle of levers and fulcrums, but the dictum also summarises an artist’s need for a starting position: a location of and for his imagination, a posture of balance, strength, and agility. Born in 1986, still at the beginning of his creative career, Ramsamoedj is simultaneously seeking, claiming, and inventing his location, his posture. Like his Flexible Man, another kind of self-portrait — mobile yet rooted, artfully attired in a garment of memories and aspirations that both conceals and flaunts, peering out at the world — he is finding his place to stand.

Detail of Flexible Man and Adjie Gilas. Photograph by Christopher Cozier

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, May 2010

Dhiradj Ramsamoedj is a Surinamese artist based in Paramaribo. He graduated from the Nola Hatterman Art Academy in 2004, and his work has been shown in a number of group exhibitions in Suriname, the Netherlands, and the United States.

Nicholas Laughlin is the editor of The Caribbean Review of Books.