Hungry for words

Karyn Olivier talks about her ACA Foods Free Library project

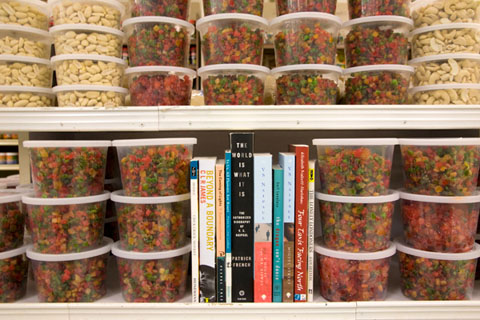

Installation views of Karyn Olivier’s ACA Foods Free Library. All photographs courtesy Karyn Olivier

The worldwide Caribbean diaspora — those millions of Caribbean emigrants and their offspring living and working in other, usually bigger and colder, countries — has unexpected footholds. Hartford, the capital of the US state of Connecticut — just over a hundred miles north of New York City — is famous for its insurance companies, and less so for its community of Caribbean residents, the third largest in North America, by some counts. They have their Caribbean Trade Council, their Caribbean American Society, their West Indian Social Club, and their Jamaican patty bakeries. And, of course, their supermarkets: culinary and cultural lifelines to “home.”

ACA Foods, on Hartford’s sprawling Main Street, is decorated with the flags of more than a dozen Caribbean countries. Its aisles are stocked with goods imported from islands thousands of miles away: everything from the necessary staples for a traditional West Indian Sunday lunch to medicinal concoctions like sulphur bitters and bay rum. In March 2010, regular ACA Foods shoppers were surprised by the appearance of a different kind of product: rows of books from and about the Caribbean — novels, poetry collections, biographies, books about history, music, and art — carefully arranged among the supermarket’s tins and bottles and packets.

Artist Karyn Olivier’s ACA Foods Free Library is exactly what its name suggests: a lending library open to all customers of the supermarket. (The project was commissioned as a public art component of Rockstone and Bootheel: Contemporary West Indian Art, an exhibition at Hartford’s Real Art Ways visual and performance arts centre, curated by Kristina Newman-Scott and Yona Backer.) At once an installation, a performance, and a kind of creative activity that stages an opportunity for social engagement, Free Library provides a practical service to Hartford’s West Indian community. At the same time, it provokes reflection on the diverse ways that cultural phenomena — whether food or literature or art — are expected to construct personal memory, social history, and national heritage.

Seeing these books tucked neatly into the supermarket shelves — Walcott’s Collected Poems among bags of dried peas, C.L.R. James’s Beyond a Boundary beside plastic tubs of preserved fruit — recalls some Caribbean writers’ symbolic shorthand of food as a stand-in for cultural authenticity or desire, or simply as a hint of the exotic to tantalise foreign readers. Olivier — born in Trinidad, now based in the US — is herself a member of the Caribbean diaspora. But Free Library is no sentimental gesture on the part of the artist, or simple assertion of belonging. Rather, it asks questions about cultural consumption, perishability, and digestion. And, of course, it is also a type of social experiment: what might the supermarket customers’ reaction to these books tell us about the practical relevance of the intangible “heritage” of Caribbean literature?

— Nicholas Laughlin

•

In early July 2010, via email, Olivier answered a few questions about ACA Foods Free Library and her other recent projects.

Nicholas Laughlin: We often talk about books and literature offering “food for thought” or nourishment for the imagination. Did ACA Foods Free Library start from a similar notion?

Karyn Olivier: Yes, absolutely. I even thought of putting a banner at the entrance saying “Food for Thought”, but settled on ACA Foods Free Library instead, which just seemed more direct. My hope was for this library to expand what we imagine the “consumables” of a market to be — particularly when that market inadvertently traffics in nostalgia for home. I was thinking it could be a place where we could really slow down, browse, and relish the sights, smells, tastes, sounds, and, yes, the imperishable produce of our West Indian heritage. I really liked the idea of borrowers returning the books when they were finished “digesting them.”

NL: How did you choose the books for your library? Are they all books you’d read, or ones that had a certain significance for you?

KO: When I first conceived of the idea, I was thinking of the relationship I have to Trinidad and my assumption that I am still tied to it intellectually, spiritually, and politically. This “given” was stoked by certain affinities I’ve inherited from the culture — say, Carnival, soca, and — jokingly — even my love of roti. But then I started to think of other signifiers of a culture, like books, and how often (or rarely) I read literature, poetry, or even non-fiction from the Caribbean.

I quickly realised that my tie to this place I still consider home was on some level a superficial one. Yes, I took a Caribbean literature class in college, and yes, I had read many classics by writers like Earl Lovelace and V.S. Naipaul, but honestly, I’m much more versed in “western” writing. This library was unexpectedly a remedy. I knew most of the Trinidadian writers and titles I wanted to include — I really love some of them, like [Merle Hodge’s] Crick Crack, Monkey and [Naipaul’s] Miguel Street — but I had to do a great deal of research to uncover the gems from the other islands.

NL: How did the library actually work? Were you able to keep track of how many books were borrowed, how many returned, and which titles were most popular?

KO: What was most exciting for me was the fact that this would be a trust library — no library card necessary, no proof of residence required, no specific date of return. I wasn’t surprised by most folks’ initial response to the library. They approached it with suspicion; surely nothing is ever really free — especially in a retail establishment, which exists for the sole purpose of exchanging goods for money. But once the customers realised this was just the relocation of a library (that ideally should already exist in this Caribbean neighbourhood) into an unexpected place (a site of commerce), they were really excited about it.

My hope is for the store to potentially be a meeting place — wouldn’t it be great to expand the function of a grocery? By day a market, at night the location of book club meetings? A utopian idea, yes, but anything is possible. The library was a gift — in turn, the West Indian community of Hartford was left to do with it as they saw fit. Will some people never return the books? I am certain. But perhaps most will understand the value in this free library — what it means metaphorically and literally, its value as “a gift of knowledge.”

NL: Inside the supermarket, how did you decide where to place specific books? Was it random, or did you work out a pattern or system beforehand?

KO: I spent time in ACA Foods combing the aisles and the products they housed, coming up with an approach. All libraries have a classification system. This library followed suit and organised itself in a similar fashion by category (i.e., region, history, children). It was critical for the books to be arranged on shelves alongside the customary products sold in the store. I liked the idea of a customer browsing through the aisles and coming across a certain title next to a desired provision — maybe it would turn out he or she actually “needed” the book more.

Certain categories were easy to decide on, like the children’s section — these books were nestled among rows of biscuits and cookies. I wanted the political books, which included charged titles like Slavery and Social Death [a comparative study of slavery in many societies by Orlando Patterson] and Avengers of the New World [a history of the Haitian Revolution by Laurent Dubois] to rub up against the hot pepper sauces — it seemed only fitting! Jamaican literature was found between loaves of hard dough bread and what seemed like endless rows of jerk seasoning.

At other times I wanted to call attention to the factions and fractions of contemporary Caribbean life. Books on culture, ranging from Trinidad’s moko jumbies to a biography of Bob Marley, were surrounded by “energy” drinks with names like “Bedroom Bully”, “Stud Power”, and “Lion King”, as well as hundred-year-old concoctions of “wood root tonics.” Nothing reminds me of happy childhood memories more than the Trinidadian black cake we make at Christmas, so I put the Trini literature near the candied fruits, in almost Proustian homage.

NL: How do you see this project fitting into the wider context of your other recent work?

KO: ACA Foods Free Library is aligned with the ideas of relational aesthetics, whose tenet is for art to create a social environment of shared activity. For the past six years, my work has increasingly been in the public realm — making work literally for the general public. This began when I made a functioning amusement park carousel for a single rider (It’s not over ’til it’s over), and placed it in a multi-purpose park in Long Island City, New York. Similarly, this past fall I completed another very public work titled Inbound: Houston, in which I converted thirteen billboard advertisements along some of the city’s busiest freeways. Each billboard hosted an image of what was located behind it — in other words, what commuters would see if the billboard wasn’t there. At moments, the billboards seamlessly disappeared into nature, performing a deft optical trick that I hoped would soothe daily commuters — a reprieve from the constant inundation of advertising imagery. Perhaps the billboards would also provoke commuters to reflect on what these “ads” might possibly be selling — of course, they’re not selling anything except (maybe) a moment of existential awareness. But, like the library project, I considered this to be a small gift to Houstonians — an unexpected moment of wakefulness or intrigue emerging from the otherwise numbing driving experience.

Another project more directly related to my Caribbean ancestry is Grey Hope, a performance/procession that was performed on the opening night of the Gwangju Biennale in 2008. I used Trinidad’s Carnival tradition as my jumping-off point. This tradition — over one hundred and fifty years old; a populist art form — creates a collaborative space, perhaps one of the first examples of relational art! So the library project, with its demand for participation from the general public, has some old and traditional roots. It is, hopefully, also a reminder to all of us — art makers, viewers, and participants — to show up, act, give, create — perhaps the only way to know we are really present, we are here.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, July 2010

Karyn Olivier is a Trinidad-born artist based in Philadelphia, where she is assistant professor of sculpture at the Tyler School of Art. She has exhibited her work at the Gwangju and Busan Biennials in South Korea, the Museum of Fine Arts and the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston, the P.S.1 Contemporary Art Centre in New York, and numerous other locations. She is the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, among other awards and grants, and has been an artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem and the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture.

Nicholas Laughlin is the editor of The Caribbean Review of Books.