Middling passages?

By Brendan de Caires

Caribbean Middlebrow: Leisure Culture and the Middle Class,

by Belinda Edmondson

(Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8014-4814, 240 pp)

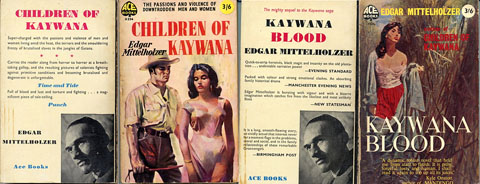

Covers of early paperback editions of Edgar Mittelholzer’s novels Children of Kaywana and Kaywana Blood. Images from the H.D. Carberry Collection of Caribbean Literature, University of Illinois at Chicago library

In The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon memorably dismisses the postcolonial middle-class as hapless intermediaries between the glories of Europe and the banalities of their complicated locales:

Here the dynamic aspect, the characteristics of the inventor and of the discoverer of new worlds which are found in all national bourgeoisies are lamentably absent . . . because the national bourgeoisie identifies itself with the Western bourgeoisie, from whom it has learnt its lessons.

Is this damning verdict true? Nearly fifty years later, are we still, culturally speaking, hiding black origins behind white masks? If not, then how do race and class signifiers influence our ideas of West Indian culture?

Wander around Port of Spain’s Queen’s Park Savannah at the height of Carnival, and the answers aren’t clear. One or two determined white women have won recognition as “real” calypsonians, which suggests some flexibility in these matters, yet Trinidad seems reluctant to choose dark-skinned girls as beauty queens (Wendy Fitzwilliam is the exception, not the rule), nor, due to a symmetrical prejudice, ones that look too white or foreign. Confusingly, we also seem anxiously ambivalent about intermediate skin tones and skeptical as to whether the middle class really can produce genuine culture. This indeterminacy makes for strange politics. The “brand identity” of Trinidad Carnival is loudly defended — some even want to trademark its distinctive features to prevent infringement by regional simulacra — but there is nothing like the same interest in or concern for an Indo-Trinidadian festival like Divali.

In Caribbean Middlebrow: Leisure Culture and the Middle Class, Belinda Edmondson wades into this cultural quicksand with revisionist zeal. By re-reading a neglected corpus of middlebrow literature, she makes the case that Fanon’s bewildered intermediaries contributed much more to our cultural patrimony than many critics have been willing to allow. As an associate professor in the departments of English and African American and African Studies at Rutgers, Edmondson is well placed to consider these questions and, happily, she writes lean, erudite prose.

Early on Edmondson sets out the prevailing orthodoxy:

As a group, the black and brown middle class were dissociated from many of the “lowbrow” cultural traditions of the black peasantry, but they were also at odds with the politics and attitudes of the white ruling elite. Critics such as Kenneth Ramchand have argued that this dissociation was cultural alienation borne [sic] of the black middle class’s isolation and, as he saw it, lack of wealth and privilege. Historian Gordon Lewis went further, painting middle-class culture in the early years as a kind of tragic mulatto problem. Like the region’s dependent political status, its culture was “sterile” and “borrowed”; middle-class Caribbean citizens were at best guilty of “militant philistinism” and at worst subject to “the cruel pressures that make life so much of a misery” for this pathetic group.

Against these sweeping dismissals, she gathers evidence that the mulattos had a clear-eyed and often original view of their culture. Far from being silenced by their putative isolation, Edmondson argues that brown musings on hybridity gave rise to a fascinating body of literary fiction, much of it still highly relevant to the cultural transactions and anxieties of the modern West Indies. If it is true that we must, as a region, eventually decide whether Shabine (Walcott’s “red nigger” in “The Schooner Flight”) is “nobody or a nation,” this book could be read as a brief for the nation-building potential of long-forgotten nobodies.

Caribbean Middlebrow is an ambitious book. In two hundred brisk pages, Edmondson surveys mid-nineteenth-century novels, fin-de-siècle newspapers, the gentrification of dialect poetry, the social politics of beauty pageants and jazz festivals, and transnational markets for popular fiction, from Edgar Mittelholzer’s novels of the 1940s and 50s to Colin Channer’s in the present. (“Much has been made of the ‘new’ sexuality that pervades so much of today’s popular literature,” Edmondson writes, “but as the covers of Mittelholzer’s books illustrate, there is nothing new about it.”) This range may sound overbroad, but I was pleasantly surprised to discover that none of the chapters felt like a makeweight. The historical breadth allows Edmondson to tease out intriguing continuities in her material, including several which will surprise a general reader. In her analysis of “early literary culture,” she writes that although the British empire remained in full control of the Caribbean at the close of the nineteenth century, its cultural heart clearly belonged elsewhere.

The marked American cultural presence has gone virtually unremarked by critics and scholars. British literature was taught; American literature was consumed. Edification versus consumption; modernity is intimately tied not simply to what we learn but to what we imbibe — what we eat, what we watch, how we play. Consumption does not reflect what we think we should be, but what we desire to be, which is not always the same thing. Jamaicans of the 1920s understood that they were supposed to be made in the image of Britain; that image, however, did not reflect the quotidian desires of the middle class, surrounded as it was by American films, American music, American popular literature. By that measure, the relationship of the early twentieth-century Caribbean to American popular culture, and Caribbean understandings of what constitutes the modern, are inescapably tied to American identity.

This insight adds depth to a telling remark in Edmondson’s chapter on popular fiction. Noting that writers like the Jamaican Channer have successfully tapped into the lucrative market for African American fiction, Edmondson pauses to consider why they bridle at the cultural associations that go with their niche. In his novel Passing Through, Channer even has a character who is himself a West Indian author warn his African American girlfriend that

after Terry McMillan, babe, the constitution of your country says that there is a book that every negress has to write . . . four sister-friends in Atlanta, DC, or LA. Places where they get to drive expensive cars . . . There you have the recipe. Go cook the people’s book.

Edmondson will have none of this patronising hauteur: “The recipe,” she observes, “appears to be one that Channer himself uses. His early novels feature main characters with obvious appeal for young black readers with professional aspirations: sexy, well-read black bohemians with glamorous occupations who move easily between the metropolitan centers of North America and the Caribbean.”

Reviewing Caribbean history through the lens of early literary novels like the anonymously published Adolphus (1853) and Michel Maxwell Philip’s Emmanuel Appadocca (1854), Edmondson shows that the brown middle class, “the most ambiguous in Caribbean social history,” always had a keen sense of its social and political dilemmas. Even before Emancipation, there seems to have been little tolerance for racial ambiguity. In the anonymous Jamaican novel Marly; or, a Planter’s Life in Jamaica (1828), the slaves warn: “You brown man hab no country, only de neger and buckra hab country.”

Endorsing Rex Nettleford’s view that the creolisation of the Caribbean is “a battle for cultural space,” Edmondson argues that:

In the literary world there are nationalist texts — and imperialist ones. There is an Afro-Caribbean aesthetic, an Indo-Caribbean aesthetic, a creolised or hybrid aesthetic, but no brown aesthetic. Regardless, both popular and critical celebrations of a creolised cultural sensibility rest on the struggles of an earlier age to define the contours of a cultural brownness that nevertheless was connected in some material way to actual, physiognomical brownness . . . I contend that these early Caribbean novels aimed to provide just such a definition of a creolised society, and that their emphasis on popular genres bespoke their authors’ desire to create a middle class that was naturalised. In other words, it was not so much an endlessly proliferating hybridity that was the goal — the celebrated “out of many, one people” model — but rather brownness as a homogeneous, consistently reproducible type.

Accordingly, Edmondson marshals a great deal of persuasive evidence to show that brown writers responded to the rhetoric of exclusion by “declar[ing] themselves to be native Caribbean citizens, if for no other reason than that, as one early spokesman put it, ‘we have nowhere [else] to go’ . . . In other words, cultural brownness is what makes the Caribbean the Caribbean, an idea that has seized the popular imagination.” Oddly enough, however, although creolité has become a dominant meme in our cultural DNA, “the brown class is associated in the minds of most scholars not with creolisation but with the cultural decreolisation of the Caribbean.”

Three editions of the Jamaica Times from 1905. Images from the Digital Library of the Caribbean, University of Florida

Repeatedly, Edmondson shows the limits of this simplistic association. Both in early brown novels and in Jamaica’s newspapers, which flourished near the end of the nineteenth century, she unearths nuanced responses to the problems of cultural identity. Some of this was due to foreign travel. Fortified by their experience of London, where the popularity of American slave memoirs and a far more tolerant social atmosphere had allowed select members of the brown middle class to befriend their English counterparts, the texts assert that, in cultural terms, the brown West Indian was the true inheritor of English culture, certainly far more so than the local whites, who lost no opportunity to emphasise their social superiority. In terms of culture and education, the browns were simply more English. In Adolphus:

An elaborate distinction is made between physiognomic Caribbean whiteness — inevitably connected with moral degeneracy and cultural philistinism — and an idealised Englishness, which is rendered in love of books and good manners, and which is apparently accessible to all. The stereotypes that Europeans held about the degeneracy of whites in the tropics were stereotypes that brown people held as well; or, as one might argue, brown people simply tarred and feathered whites with the same stereotypes as those held by whites of brown people. At any rate, in contrast to the conventional scholarly view that the early brown middle class simply wished to be white, Adolphus makes a point of showing that its brown characters are proud of their brownness and have no desire to be otherwise.

Ironically, given its author’s political sympathies, one of the texts that sheds most light on the cultural progress of the brown middle class is Jane’s Career (1914), by the Jamaican novelist H.G. de Lisser. After an intelligent and nuanced account of de Lisser’s life and work, Edmondson concludes:

[He] clearly had an investment in preserving the old colonial order. [Yet, if] we consider that de Lisser was a brown man until he was “whitened” by his enhanced social pedigree, his searing indictment of brown middle-class pretensions may be read as an erasure of his own past. Jane’s “career” from poor black peasant to “browned” middle-class matron reveals the blackness latent in brown middle-class respectability; by contrast, de Lisser made no such examination of the white elite society to which he claimed allegiance. The mystification and reinvention of ethnic and class origins are, after all, a brown story.

Edmondson also writes well on beauty pageants, the transmigration and/or importation of Trinidad Carnival into other islands, and the elasticity of what constitutes “jazz” at the St Lucia Jazz Festival. My only real grouse at the end of this clever book was that there was surprisingly little analysis of recent Trinidadian calypso and rapso. If the meanings of Louise Bennett can be parsed for a chapter, and the long-shot success of Denyse Plummer merits consideration, surely a few pages on David Rudder and 3Canal and their appeal for today’s “brown” Trinidadians wouldn’t have gone amiss. That aside, this book certainly deserves a slot on any shelf reserved for the serious study of West Indian culture.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, July 2010

Brendan de Caires was born in Guyana and now lives in Toronto. He has worked as an editor for various publishers, and written book reviews for Caribbean Beat, Kyk-Over-Al, the Stabroek News, and the Literary Review of Canada.