Moving pictures

A portfolio of images from Suriname’s painted wilde bussen

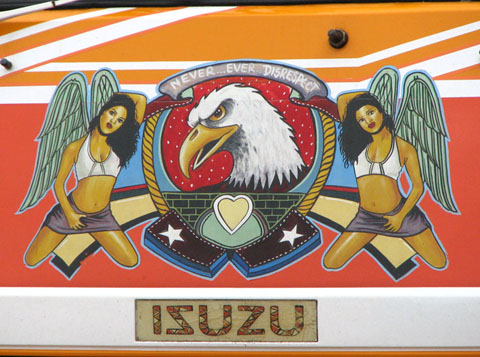

Painting on a minibus in downtown Paramaribo, June 2009. Photograph by Nicholas Laughlin

Paramaribo’s numerous public monuments — statues, columns, plaques — commemorate historic events, official heroes, and ancestors, whether real or ideal, of Suriname’s major ethnic groups. They collectively tell the story of a colonial enterprise shaping itself into a nation, with all the political and intellectual implications of that n-word. But the city also contains a mobile pantheon of very different culture-heroes, suggesting an alternative nation-story, and alternative insights into how contemporary Surinamese understand and imagine themselves.

Stand on the pavement along certain streets downtown, at certain intersections, and a constantly changing gallery of pop culture icons zooms past. Bollywood stars and Hollywood starlets, dancehall musicians, multiple incarnations of Bob Marley, and even political figures like George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Saddam Hussein: painted with varying degrees of likeness and finesse on the exterior panels of the city’s privately owned minibuses.

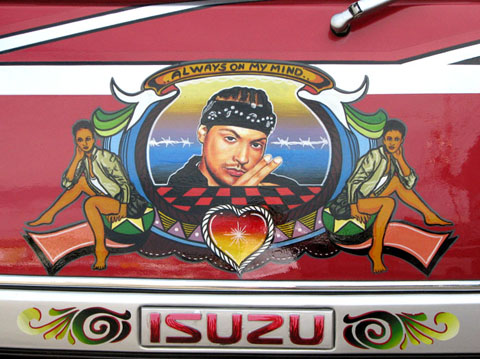

Paintings on minibuses in downtown Paramaribo, June 2009. Photograph by Nicholas Laughlin

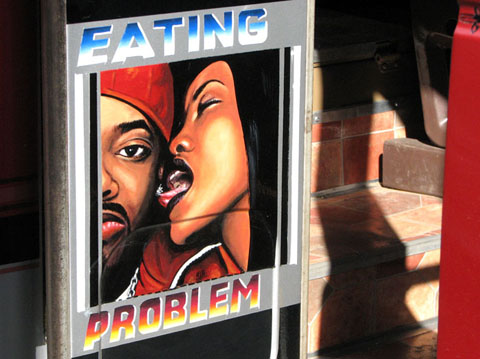

Paramaribo’s wilde bussen — literally, “wild buses” — have a distinctive iconography and their own pictorial conventions. The front panel below the windscreen usually features a graphic resembling a heraldic escutcheon: a main portrait — anyone from Sean Paul to Arnold Schwarzenegger to a Hindu deity — on a central shield or medallion, with two “supporters” on either side — often scantily dressed young woman in come-hither poses. Stylised creatures like birds or horses are arrayed symmetrically to complete the effect. The side panels might feature more naturalistic portraits of actors and musicians, or slogans with fanciful lettering. Gas-tank covers and tyre mud-flaps come in for special attention. Religious symbols and insignia like firearms, hearts, and roses are other favourites.

The combinations of images and words can be amusing, surreal, occasionally even disturbing. One bus juxtaposes a ganja-filled pipe with a miniature portrait of Osama bin Laden. Another, which I photographed in February 2010, flaunted a prophetic portrait of the former military dictator Dési Bouterse with army cap and ominous dark glasses. A painted motto read “Basi Joeroe”: “the boss’s time” — or “time for the boss.” Six months later, to the dismay of many Surinamese, Bouterse was sworn in as president, after an election in which his party won the largest block of seats in the legislature.

Painting on a minibus in downtown Paramaribo, February 2010. Photograph by Nicholas Laughlin

Painted buses are not unique to Suriname, and most wilde bussen seem restrained compared with the pattern-encrusted tap-taps of Port-au-Prince, or the diablos rojos of Panama City, some of them tricked out with neon. These decorated buses energise the urban spectacle of their respective locations, but also serve a practical purpose: they are visual projections of their owners’ and drivers’ personalities and tastes, and — of course — canny advertising strategies. In Paramaribo, the specific images painted on a bus usually indicate the parts of the city it services: Bollywood icons for Indo-Surinamese neighbourhoods, dancehall stars for Afro-Surinamese areas.

It’s easy to forget that these bus decorations also display the creative ambitions of the individual artists who paint them. These largely unknown contributors to Paramaribo’s visual environment are recorded in Schaafijs & Wilde Bussen: Straatkunst in Suriname, a new book by artist Tammo Schuringa, art historian Paul Faber, and art critic Chandra van Binnendijk (KIT Publishers, ISBN 978-946-022054-8, 158 pp; in Dutch). The authors give a comprehensive history of the wilde bussen paintings, beginning in the early 1970s with the artist Eric Gillis, whose work has long disappeared. Today’s buses demonstrate the influence of two main “schools” of painters: one led by Ramon Bruyning, specialising in dancehall and hip-hop stars, the other by the Khodabaks brothers, Nishar and Johnny, dealing in Bollywood imagery. (Schaafijs & Wilde Bussen also catalogues the decorations on Paramaribo’s schaafijs or “shaved ice” carts, and advertising murals painted on shops and supermarkets.)

As Schuringa, Faber, and van Binnendijk make clear, this straatkunst or street art is “a form of expression determined by supply and demand.” The bus, ice-cart, and shop-wall paintings are transactions between their makers and the small-scale entrepreneurs who commission them: financial transactions, yes, but also creative negotiations between artist and client, between individual expression and public expectations. This compromise between imagination and the market also influences the kind of art we see in galleries and museums. But the painted wilde bussen — whose portraits must eventually fade or dent or simply fall out of fashion — more openly, less dissemblingly ply the route between personal aesthetics, communal fantasies, and profit margins.

Nicholas Laughlin

Painting on a minibus in downtown Paramaribo, June 2009. Photograph by Nicholas Laughlin

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, July 2009

Nicholas Laughlin is the editor of The Caribbean Review of Books.