Make it new

By Dylan Kerrigan

The Thought of New World: The Quest for Decolonisation,

ed. Brian Meeks and Norman Girvan

(Ian Randle Publishers, ISBN 978-9766-3740-1-3, 360 pp)

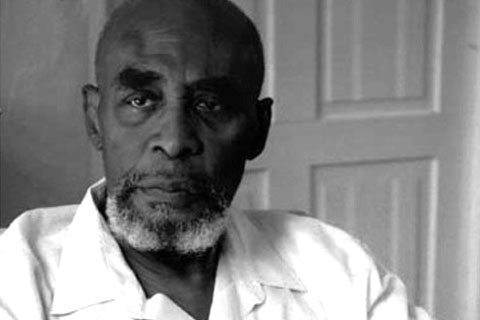

Lloyd Best, 1934–2007; photograph courtesy the Lloyd Best Institute of the West Indies

The Thought of New World is not an account that seeks to promote a neglected group of Caribbean thinkers to the list of anti-colonial figures already well known for their work on the decolonisation of political and economic thought. Rather, it is a text that offers a sophisticated behind-the-scenes look at the work and personalities involved in a rich period of post-independence Caribbean thought in the 1960s and 70s. It covers a space and time where and when alternatives to imported models and practices in politics, economics, and development were proposed, and a rethinking rooted in the Caribbean condition and experience took place. The book captures a sense of this richness of thought and critical discussion by presenting a compilation of many of the debates and papers delivered at the fourth Caribbean Reasonings conference held in June 2005 at the Mona campus of the University of the West Indies. The conference was designed to evaluate and reinvigorate the ideas of the New World Group, and The Thought of New World uses retrospection as a way to pull important debates — dissolved by three decades of postcolonial neo-liberalism — back into the picture.

The New World Group was a theoretically robust, empirically light, and loosely defined intellectual movement established in the early 1960s among young lecturers, students, and other thinkers at the Institute for Social and Economic Research at Mona, led by the Trinidadian economist Lloyd Best (who died in 2007). New World’s radical ideas included Caribbean integration and a rejection of many local political leaders of the time. Its original energy was nurtured by other regional social scientists, and spread from Jamaica to Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago, the Leewards, and the Windwards. Much of the thinking and ideas generated by the group were published in the widely read New World Quarterly out of Jamaica, and the New World Fortnightly (edited by the late David de Caires) out of Guyana. As the reader will find out, a list of those connected to New World is a veritable who’s who of some of the best-respected thinkers the Caribbean has produced.

The Thought of New World is a journey through the emergence, impact, and legacy of the New World Group. It stands on the shoulders and narratives of the various scholars who attended the Mona conference, including many of the original members of the group, such as Best, de Caires, James Millette, Kari Levitt-Polanyi, and Norman Girvan. The book also includes scholars who can claim they were influenced by the intersection of ideas included in New World thought: persons such as Michaeline Crichlow, Kirk Meighoo, and Dennis Pantin. This blending of thinking across generations gives the book’s subject matter its form, and to facilitate this division of content and temporal framing The Thought of New World is divided into three subsections: “Reflecting”, “Imagining”, and “Remembering”. These are supported by Brian Meeks’s personal introduction, in which he identifies some core themes common to the essays and their many authors. They include the illumination of an ephemeral time, a concern for the potential loss of important gains, and the politics behind why the movement eventually splintered.

The editors, Girvan and Meeks — both members of the original group, before drifting into other spaces, and both current faculty members at UWI, at St Augustine and Mona respectively — do a thorough job of unpicking the myths, accusations, and realities behind New World’s own internal politics. In the first section, they call on the support of other original members to recount their memories. Girvan goes first, with a historical review and insider perspective on the rise and fall of the New World Group, in which he presents seven general theses he discerned in New World thought and describes the vibrant intellectual atmosphere at its inception. He reminds us that, for Caribbean thinkers, the late 1950s and early 60s were like being on the cusp of the unknown, and part of a “third world” hungry to break out of its colonial chains. For Girvan, the times fed and fired the minds and souls of many of the young people who became part of the loose political discussion groups that were the genesis of the New World Group. Among various intellectual viewpoints, these minds agreed on and believed in the need for independent thought, the problem of escape from the colonial condition, the conceptualisation of the Caribbean as a plantation system, and the structural violence of economic dependence on multinational corporations and foreign governments.

The first section of the book continues with political scientist James Millette offering the reader another historical narrative and perspective on matters to do with both the emergence and the decline of New World, one which appears at odds with many of the other voices collected here. His tone, at times, is disgruntled and argumentative, but his passion seems to stem from a disappointment at New World’s inability to stay together — and the resulting lost opportunities to act as a force to counter the neo-colonial status quo that rushed in after independence — rather than any denial of the group’s significance.

Economist Kari Levitt-Polanyi’s contribution sheds light on the diasporic Caribbean influence on New World thought, in particular that from West Indians living in Toronto. However, what most interests me in this chapter is the one paragraph where Levitt-Polanyi discusses the production of one of the most influential and lasting theories of the period, that of the Plantation Economy. The reader might be surprised to learn that while Best certainly contributed the basic ideas of the Plantation Economy theory, he contributed far less to the formalising of its insights.

Part two of The Thought of New World builds on the ideas generated in the New World Group’s inception, and asks how such ideas live on in Caribbean scholarship. The late economist Dennis Pantin provides an essay drawing on the Plantation Model hypothesis and links it to the Open Petroleum Economy Model to offer an interpretation of the rentier economy — in which the state derives its income from “renting” its resources to foreign governments or corporations — defined by the inevitability of corruption. Michaeline Crichlow and Patricia Northover engage Best’s critique of metropolitan epistemology as a starting point into new forms of social analysis that include such sweeping ideas as “fleeing the plantation” and improving the ontology of social change in the Caribbean. And Kirk Meighoo’s contribution builds on his close personal relationship to Best. They offer a key to better understanding Best’s intellectual lexicon, as well as excavating his observational methodology rooted in local conditions and the history around him. All the essays in this section do an excellent job of attesting to the continued salience and transformation of the original analysis offered by the New World Group.

The final section — “Remembering” — is given over completely to Best himself, via the transcript of an interview conducted in 2005 by Anthony Bogues, Girvan, and Meeks at Best’s home in Trinidad. It is full of such gems as Best’s thoughts on integration and regionalism, the legacies of New World, the Cuban Revolution, and the origins of the Plantation Model, to name just four small aspects of a much larger mass. The interview should be read more than once — it is impossible to take in all its insights in one reading, and at over a hundred pages long it could stand as a published volume by itself.

While there is still much debate over the exact dates of the New World Group’s emergence, how long it held together as a veritable movement, and when and how exactly it ended, there is near unanimous agreement on the role Best played as an intellectual catalyst for its original evolution. The editors’ ability to bring Best’s thinking and viewpoint to life in this insightful interview help further illustrate the broad and far-reaching significance of New World thought. There is a “final word” feel to the interview, too, as though Best is responding to and enlightening many of the questions and statements all the other contributors in the collection raise in their own narratives. In this way, readers both old and new get a refresher on Best’s take on New World — what it was, what it was striving for, and why it dissolved.

•

The brilliance of The Thought of New World is not only its reinvigoration of the Caribbean quest for decolonisation across the spheres of economics, politics, and culture, but also its illustration of a hybrid transnationality that brings form to Caribbean thought. We still don’t know if the quest for decolonisation is ever fully attainable, but in the stories and analyses the editors bring together here, there are tales of the different yet similar national contexts which Caribbean thinkers found themselves confronting. This retrospective may not provide the answer to decolonisation, but it is able to manifest various national strands of regional thought into a productive body of Caribbean critique and depth: mapping times and circumstances to the national and intra-national paradigm alive in thought at the time of Independence. In this sense, and in its meticulous accounts of a range of intellectual contexts, the book is about far more than “New World thought.” It is a riveting and persuasive analysis of the national and supra-national contexts on which the processes of neo-colonial “progress” depended, and some of the strategies proposed at the time to contest it.

From a personal point of view, what most pleases me about this collection of essays is the way it provides comprehensive background to an intellectual movement that many of us born after its heyday have only read about and heard about sporadically. From my parents, their friends, and more recently my older academic colleagues I have often heard stories of the vibrant discussions that unfolded and papers that were published first under the umbrella of the New World Group and later by splinter movements centred on journals like Moko, Tapia, and latterly the Trinidad and Tobago Review. It is helpful to know how many great minds of Caribbean thought from the Independence era are interconnected through friendship, acquaintanceship, and work — how they limed together, argued together, and grew up together, some falling out beyond repair and holding onto grudges now over thirty years old. In this sense, The Thought of New World not only provides a glimpse into a cross-pollination and inspiration of ideas that we can retrospectively call Caribbean thought, it also speaks to our twenty-first-century Caribbean condition itself. It asks readers a much bigger question: what would it take today to produce a meeting of regional minds similar to what the New World Group gave the region in the 1960s? Perhaps, reading between the lines, this is the tragedy James Millette forcefully laments in his contribution, and which Lloyd Best can no longer answer for us.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, March 2011

Dylan Kerrigan is an anthropologist teaching at the University of the West Indies, St Augustine. His recent research looks at the relationship between the accumulation of capital and the shifting construction of difference in nineteenth- and twentieth-century urban Trinidad.