Out of Africa

By F.S.J. Ledgister

Changó, the Biggest Badass (originally published in Spanish as Changó, el gran putas), by Manuel Zapata Olivella, trans. Jonathan Tittler, with an introduction by William Luis

(Texas Tech University Press, ISBN 978-0-89672-673-4, 463 pp)

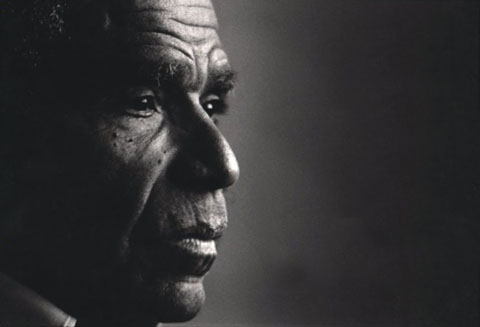

Manuel Zapata Olivella

When I was in high school, I discovered G.R. Coulthard’s Race and Colour in Caribbean Literature (1962). (I learned recently, to my horror, that my high school no longer has a library, so a curious young person can no longer have similar experiences.) To my very naïve surprise, Coulthard focused on writers from the hispanophone and francophone Caribbean, with writers from the English-speaking Caribbean a mere afterthought.

That was my first introduction to the idea that the Afro-Caribbean literary experience was something that went beyond the bounds of the English language. That library also contained — and I read — Joaquim María Machado de Assis’s Epitaph for a Small Winner (1880), without any indication that the Brazilian novelist was a man of as much African descent as Alexandre Dumas, père. I went on to encounter the work of novelists, both of the Hispanic Caribbean and from mainland Latin America, who engaged the subject of race, in particular the African presence, in the most direct way. Now I’ve read Manuel Zapata Olivella’s Changó, perhaps the most extraordinary Latin American novel of race written in the twentieth century, and one that belongs in the canon of the circum-Caribbean as much as does the oeuvre of his fellow-Colombian Gabriel García Márquez.

Zapata Olivella (1920–2004) was a Colombian physician, writer, and anthropologist, whose literary output, between the 1940s and 1980s, included six novels, five collections of short stories, and four plays — most, it appears, focused on the life experience of the people of the Caribbean coast of Colombia; in the main, on the indigenous and black inhabitants of that region. Hardly surprising for someone who grew up in Cartagena de Indias. Zapata, from his youth, wrote for the newspapers of Cartagena and Bogotá. His working experience included the practice of medicine in both Colombia and Mexico, and ethnomusicological research in the United States (a country which he defended until he experienced racial discrimination there). He and his sister Delia managed to squeeze in founding a dance company. One short biography describes him as engaging in “various activities” in the 1940s, including serving as Colombia’s consul in Trinidad and Tobago. He was to go on to teach at universities in Central America, Canada, Africa, and in the United States, and establish the literary magazine Letras nacionales.

Zapata was a significant figure in the Latin American Boom, a recipient of the Esso Prize (for Detrás del rostro [“Behind the Brow”], in 1962), and the Casa de las Américas Prize (for Corral de negros [“Black Slum”], in 1963). In 2002, towards the end of his life, the Colombian ministry of culture awarded him a prize for his life and work (Premio a la Vida y Obra). Changó, el gran putas, though not a prizewinning work, appears to be his most significant novel.

It is a tale, mystical, mythical, and poetic, that gives us the story of Africa in the Americas, from the arrival of black slaves in the Caribbean and South America in the sixteenth century to the Civil Rights struggle in the United States in the twentieth. The unifying theme is the presence of the Yoruba divinity Shango (or Changó, as the translator leaves him untranslated from the Spanish) over the centuries. The overall effect, given the historic reach, the episodic structure, and the surrealism with which the novel is infused, is as if a novel by Alejo Carpentier — on a larger scale than The Kingdom of This World or Explosion in a Cathedral — had been crossed with Kamau Brathwaite’s poetic epic The Arrivants.

•

Indeed, the novel begins with a poem, one that is reminiscent, in its African tone, or at any rate in its use of African divine names, of Brathwaite. The poem establishes the setting for the stories that follow. The first of these has to do with the slave trade, and it, in its turn, establishes the key terms that will resonate throughout the novel: the White Wolf who will persecute the children of Changó and the ekobios, the brothers and sisters, who will endure and survive the terrors that the White Wolf will inflict on them, the Muntú, the individual African people who populate the novel. It culminates with a revolt on a slave ship led by Changó himself.

The second story involves the revolt of the enslaved blacks of Cartagena de Indias in the early seventeenth century, under the leadership of Benkos Biojo. This was one of the earliest Maroon wars in the Americas, resulting in the freedom of the Palenque of San Basilio. Zapata builds his story around two historical figures: Benkos Biojo, and his capture and execution as a heretic (for having maintained the worship of his ancestral gods); and the Jesuit missionary St Peter Claver, whom he presents as the only white person worthy of the heroic Biojo’s respect.

The death of Benkos Biojo is followed by the poetic statement of defiance that

a night in chains

does not enslave the soul.

What comes next is the story of the Haitian Revolution. Zapata gives us a dizzying array of voices — Toussaint, Dessalines, Christophe, Bouckman, Napoleon, the mulatto woman Marie-Jeanne — to provide us with the narrative. The purpose of his complex, surreal account is laid out clearly, sharply, and frankly:

Our struggle for liberation has been reviled with the false stigma of a racial war. If the White Wolf oppressed, murders, and will despoil, his cruelty, always perfumed with incense, is adjudged as civilising. When the slave resisted, exploded his chains, and defeats the master, his action is homicidal, racist, barbarous. For the Wolf’s forgetful scribes, the history of the Republic of Haiti will always be the fanatical and hate-crazed blacks’ massacre of their white brothers, never the slave-owners’ genocide against a defenceless people.

The tale of Haiti is followed by that of Simón Bolívar, narrated by his wet nurse, Granny Taita, who hears a prophecy in the thunder that “By Changó’s order the infant boy who sucks your milk will be the liberator of many nations!” That, in turn, is followed by the story of the black Colombian José Prudencio Padilla, who fought for Spain at the Battle of Trafalgar, and then fought for independence against the Spanish Crown. Padilla was executed in Bogotá as a rebel against the newly independent state.

After Padilla comes the eighteenth-century Brazilian architect and sculptor Aleijandinho, who saw visions of “the Purest Virgin with the African face of her son, the same one I gave Jesus when I sculpted him preaching to his people.” Aleijandinho (“Little Alex”) was an extraordinary artist who overcame not just the impediment of race, but the even greater impediment of leprosy, which removed his fingers. He channels the history of the black experience of struggle and revolt in Brazil, including the great Gunga Zumbí, the Maroon leader of the seventeenth century.

Aleijandinho’s story is followed by that of the Mexican priest José María Morelos, a hero of the war of independence. This section of the narrative is the vehicle for some classically liberal statements, for example: “Let slavery and racial discrimination be proscribed forever, leaving all persons equal. Only virtue and vice will distinguish one American from another” — with “American” here having its Spanish sense of “inhabitant of the Americas.” The tale of Morelos is succeeded by that of the fictional Agne Brown, who links Marcus Garvey, Burghardt DuBois, Booker T. Washington, Martin Luther King, Nat Turner, Frederick Douglass, Malcolm X, and several other historical figures into a single long recital of the sorrows and survival of the black people of North America, moving from slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction, and Jim Crow into the Civil Rights era, through jazz, the blues, Memphis, New Orleans, Chicago, and the Harlem Renaissance. The history of African-Americans is told at a dizzying pace, until we find ourselves face to face with Changó and Elegba naked, who warn us that, for the living, time is not inexhaustible.

The final segment of the book is a glossary listing all the terms used in the novel, under the wonderful heading “Book of Navigation”. For, indeed, this is a book that needs to be navigated, almost as much as read.

William Luis, in his introduction, provides the reader with some useful perspective on the novel, both by comparison with Carpentier and lo real maravilloso (which he renders as “Marvellous Realism”) and in Zapata’s own context as an Afro-Latino writer who is “the most significant Afro-Spanish-American narrator of the twentieth century.” He wonders whether, had Zapata Olivella lived long enough, he would have incorporated the election of Barack Obama into the novel (perhaps seeing Obama as a prophet in the line of Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey). That might be possible, though Luis’s hope that “with Barack Obama’s presidency the Ancestors and Orichas may finally be smiling” might be a little far-fetched.

•

We are reminded, regularly, that this is a translation, by the infelicities of the translator. For example, Marcus Garvey was not born in “Santa Ana Bay.” The translator, while managing to render Alfred Hayes’s I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night accurately, produces this:

If we must die

Let it not be like swine . . .

But with our backs to the wall

Die killing

Fire back!

instead of

If we must die, let it not be like hogs . . .

Pressed to the wall, dying, but fighting back!

when turning Claude McKay’s lines back from Spanish into English. It isn’t as if McKay’s poem is not easily available, or recognisable (and in fact the butchered lines quoted above are prefaced with “My countryman Claude McKay declaims in one of his poems,” words put in the mouth of Marcus Garvey).

In his note at the beginning of the book, the translator points out that the novel was a difficult text to render into English, and that some contemporary theories of translation have favoured “resisting the temptation to ‘domesticate’ foreign or alien or culturally different texts, making them more accessible to ethnocentric first-world readers.” The assumption that all English-speakers live in the First World is, let us say, staggering.

Leaving this cavil aside, this is a marvel of a book, to be savoured slowly over days, or even weeks. The distillation of a history and a hemisphere into a few hundred pages serves to remind us that the dead can speak loudly to the living.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, March 2011

F.S.J. Ledgister is a British-born Jamaican. He teaches political science at Clark Atlanta University in Georgia, and has published work on Caribbean political development and political thought.