Brave new world

By Annie Paul

Young Talent V, curated by David Boxer and Veerle Poupeye

(Marvin Bartley, Keisha Castello, Stefan Clarke, Michael Elliott,

Christopher Harris, Marlon James, Leasho Johnson, Megan McKain,

Oliver Myrie, Dion “Sand” Palmer, Ebony G. Patterson, Oneika Russell, Caroline “bops” Sardine, Phillip Thomas)

National Gallery of Jamaica, Kingston; 16 May to 10 July, 2010

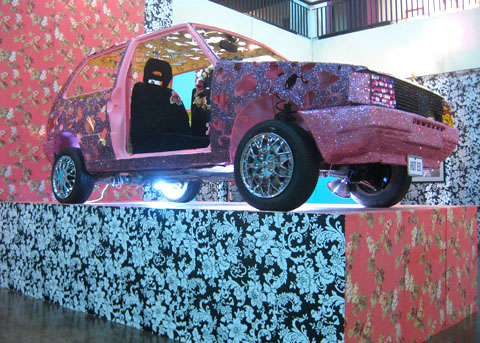

Cultural Soliloquy (Cultural Object Revisited) (2010), by Ebony G. Patterson; car, wallpaper, fabric, glitter, rhinestones, sound, rims, and hand-cut elements; dimensions variable. Image courtesy the National Gallery of Jamaica

If art is any indication, issues of class, gender, sexuality, power, and money are confusing the fuck out of us. But interestingly, not so much race . . . It seems well defined and accepted that our collective psyche is Afro-Jamaican. Overall, though, what was most striking was just how dark and confusing a place we are culturally right now . . .

— amalgamated responses to Young Talent V

from @bigblackbarry on Twitter

The consensus is that the National Gallery of Jamaica’s Young Talent V survey was a resounding success, marking a decisive shift in artistic ground, not unlike the infamous 1997 Saatchi show Sensation that launched the career of the Young British Artists. Whether Young Talent’s fourteen young and mostly Jamaican artists go on to have stellar careers remains to be seen, but the constraints of their location — a small place with a business class not well versed in the vocabulary of contemporary art — portends otherwise.

Young Talent V is the latest in a series of exhibitions curated by the National Gallery whenever a quorum of noteworthy new talent is aggregated. The first Young Talent was held in 1985, followed by exhibitions in 1989, 1995, and 2002. As the catalogue states: “The Young Talent exhibitions have been scheduled whenever the NGJ curators felt that a sufficiently large cohort of promising young artists had emerged to make a strong statement about new directions in Jamaican art. Now is undeniably one such moment, with exciting and provocative new art that responds actively to the present socio-cultural moment and challenges much of what was previously taken for granted in the Jamaican art world.”

A breathtaking departure from average Kingston artistic fare, the latest Young Talent has firmly reinstated the reputation of the Jamaican contemporary art scene, which had been languishing in recent years. Unfortunately, the show maintains the problematic distinction insisted on by the Jamaican curatoriat between a putative “mainstream” and “intuitive” artists; the latter are supposedly not only untrained but also unspoiled, and unencumbered by art history or familiarity with the Western canon. This edition of Young Talent featured two new “intuitives,” Christopher Harris and Dion “Sand” Palmer, and twelve products of conventional art training.

The artists range in age between twenty-five and thirty-nine. Five of the fourteen are women; one of them, Ebony G. Patterson, dominated the show with her exuberant multimedia works, which included a blinged-up car and rhinestone-studded portraits of young men in colourful, lace-bedecked garb and make-up. Represented in familiar agonistic poses spun from Kingston’s fervid dancehall culture, Patterson’s innovative tapestry works riffed on the contradictions of Jamaican masculinity, that curious brew of extreme machismo laced with fantastical frills and foppery. Is this the outcome of a “born fi dead” culture that incubates young thugs raised by grandmothers with a penchant for Victoriana?

The titles of some of these works gesture at earlier “masterworks” of Jamaican art history. In Daadi + Yutez (Mother and Child Revisited) Patterson references an earlier Barrington Watson painting depicting a mother and her young son. In Patterson’s version it is a young man who defiantly holds his baby, accompanied by a masked child; both parent and child gaze back at the viewer through impenetrable sunglasses. In similar vein, Gully Godz in Conversation cites Watson’s Conversation, a painting of skirt- and scarf-clad black women talking to one another, while Cultural Soliloquy quotes Dawn Scott’s 1985 installation A Cultural Object. The Counting Money HaHa refers to an iconic painting by Albert Huie titled The Counting Lesson.

In these revisions or quotations of earlier, much cherished Jamaican artworks, Patterson captures some of the seismic shifts that have taken place in artistic and other languages in Jamaica. The shift, for instance, from standard English to Rasta talk to the pungent urban Patwa of today can be mapped onto the nineteenth-century English realism of Barrington Watson, the Rastafarian-inflected work of Dawn Scott, and Patterson’s new work, which raps fluently in contemporary Jamaican. The artistic lingo Patterson has minted is also inflected by the vocabulary of African-American artists such as Kehinde Wiley.

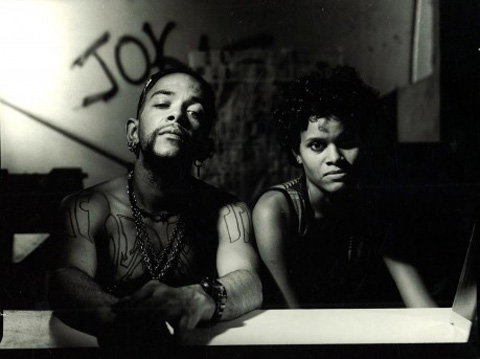

Stefan and Camille (2007), by Marlon James; digital black and white photograph (digitised from negative). Image courtesy the National Gallery of Jamaica

If Patterson’s works are fantastical odes to excess and nuffness, a species of Jamaican rococo, Marlon James (unrelated to the Jamaican novelist of the same name) captures a different Jamaica through a camera lens mimicking the stark, plain pseudo-truths of cinema verité. His portrait subjects are unsmiling yet vulnerable, compelling in their simplicity. Stefan Clarke’s moulded wood and metal body masks are simultaneously sinister and attractive objects in themselves. His photographs of models wearing the artworks are reminiscent of Khari Darby paintings, with all the connotations of bondage, capture, entrapment, and mutation to be found therein.

Marvin Bartley’s photo-based work embodies displacement and catastrophe, depicting anonymous black bodies stripped of clothing but not dignity. His moving Tragedy of Zong series refers to the infamous slave ship heading for Jamaica in 1781 whose captain threw 132 ill but still living Africans overboard, rather than risk infecting the rest of the “cargo.” Bartley’s Enthroned Madonna impassively surveying a sea of writhing black bodies is at once lyrical and disturbing. His classical vignettes are masterpieces of digital editing and cloning techniques. Another classicist, Phillip Thomas uses the medium of oils to render grand canvases bearing sumptuously painted images of circuses, fairs, and arenas. Whereas earlier works such as Singularity display masked bodies similar to those portrayed by Clarke (and Darby), Thomas’s more recent paintings, Carousel and Matador, seem to shake off the Jamaican preoccupation with medieval grotesquerie, though a whiff of Bacon still lingers.

Untitled (2003), by Oliver Myrie; oil on canvas; 40.8 x 38 cm.

Image courtesy the National Gallery of Jamaica

Painting is a staple of Jamaican art, and another unique talent emerging in this show is Oliver Myrie, whose expressively pocked, grated, and spotted canvases display a profoundly felt sense of colour and nature. Another painter, Michael Elliott, leans towards extreme-close ups of used, spent subjects — whether dead rats, June bugs, cigarette butts, bullets, or hypodermic syringes — treated in a photorealist manner. Notable exceptions are Infinity’s End, a study of uncooked noodles, and The Trillionaire, a damning portrayal of Robert Mugabe enthroned in a decaying building, with a mound of skulls, dollar bills, and detritus around him. The latter is almost the only work in the Young Talent that comments on international issues. Elliott’s Tous Saintes and some of Patterson’s work, notably the tryptych Di Real Big Man, reference Haitian history and its terrible present.

Keisha Castello’s works are intense studies of internal struggles, simmering with violence and repressed horror. At the same time there is a delicacy in her earlier works not to be found in the bloody overturned Chair series of 2010. Works by Leasho Johnson and Oneika Russell, meanwhile, lean towards caricature. The latter’s simple laserjet-printed drawings from her Drift series remind one of the work of Miami-based artist Hernan Bas.

Megan McCain’s jewellery pieces, though beautiful, seem external to the rest of the show. And the hapless “outsiders” Sand and Christopher Harris hover around its margins. Sand, who was encouraged to draw and paint by Melinda Brown of Roktowa, produces eccentric drawings of life in downtown Kingston and Anansi figures from Jamaican folklore. His style is at once tentative yet sure-footed, and a sense of humour pervades the treatment of his subject matter. Harris’s attractive pop art and music-inspired paintings are reminiscent of the psychedelic art of designers such as Peter Max and Milton Glaser.

The other outsider in Young Talent is the Vincentian artist Caroline “bops” Sardine, currently based in Jamaica, whose work looks like the kind of multi-coloured toy-like objects one sees at Caribbean craft markets. A closer view reveals sinister references that belie the fairy-tale façade of the assemblages, but there was a little too much going on, a time-consuming cornucopia of detail, and one was repelled by the work rather than drawn into it. More fascinating and compelling than the works themselves are the eccentric titles bestowed on them. There is a Brathwaitean lingustuic creativity at play here, and “bops” milks orality with skill and guile; her manipulation of sound and language and her rendering of spoken Creole is nothing short of brilliant. beeez pitch pan sheee; calameetee clamp sheee; she sed harr ancestors protected haar; ah tru tru tor.e; The Xtorshonists . . . NOW PLAYIN: the titles hint at personal tragedies as well as public misdemeanours — the phenomena of extortion and generalised corruption that plague societies globally.

The curatorial team of Veerle Poupeye and David Boxer, assisted by O’Neil Lawrence, should be congratulated for pulling together an extraordinarily vibrant show showcasing the best of a new generation of Jamaican artists. The artists themselves deserve applause for abandoning the twentieth century preoccupation with “heroic,” individualistic art-making that has such a firm grip on the Jamaican art scene, and engaging in lively conversation with each other. As Poupeye points out in the catalogue, the collaborative approach demonstrated by several artists in the show is unprecedented. This is a group of young artists literally posing for one another, often physically visible in each other’s work, working together instead of against or in spite of each other. Their creativity and productivity are also a tribute to the Edna Manley School of Art, where much of this artistic talent was nurtured.

One drawback of the National Gallery’s conceptualisation of Young Talent is that it allows little room for the inclusion of artists who are neither art school graduates nor sufficiently marooned from art historical “knowledge” to fall into the benighted “intuitive” category. A survey of young talent that overlooks the formidable self-taught polymath Peter Dean Rickards, whose contribution to the visual culture of Jamaica cannot be overemphasised, is missing something crucial, unique, and beyond the rigid scaffolding of traditional art categories. Likewise, I would have expanded the “intuitive” category by including the “sobolious” L.A. Lewis, whose semi-literate graffiti accompanied by his famous tag mark the Kingston landscape as effectively as a male dog marking territory. “Big up the ploice. L.A. Lewis” or “L.A. Lewis. The pore love you” are insertions into Jamaican visual culture that ought not to be overlooked. A wizard at hype and self-promotion, Lewis has managed to create a brand for himself without a product; the product is himself. As another Twitter commentator, @therealnickmack, remarked: “He’s unlocked some kind of marketing algorithm written by one of the Old Masters.”

Detail of Enthroned Madonna (2010), by Marvin Bartley; digital print on archival paper; 109.2 x 241.3 cm. Image courtesy the National Gallery of Jamaica

Photography-based work and painting were the dominant media in the show. If Young Talent V is a harbinger of the future of Jamaican art, it is worth noting there isn’t the slightest inclination towards the medium of performance. Performance-based artwork has increasingly emerged in Trinidad and Tobago, for instance, and in the wider Caribbean, but for reasons unknown has failed to find a foothold in Jamaica. There is fodder for a research paper on why this is so.

The catalogue for Young Talent V is a welcome departure from the standard staid, black and white National Gallery template for its printed documents. At the same time, as a visiting curator pointed out, far too much space is devoted to large photographs of the artists and texts by and about them, and not enough to reproductions of their work. Considering how short the exhibition run was — barely two months — the catalogue as visual document becomes crucial for archival purposes. It’s a pity the designers seem not to have thought of this.

As the perceptive music producer @bigblackbarry put it in on Twitter, although much of the work in Young Talent accurately hints at the troubled state of contemporary life in Jamaica and the Caribbean, there is a seeming acceptance of the fact that this is a primarily Afro-Caribbean society; as such there is no identity crisis haunting us any more. With their deliberate focus on “the careful craft of showcasing and presenting certain bodies” (shades of L.A. Lewis) — that is, the neglected black body, whether abjectly naked or hyper-accessorised in baroque splendour — artists such as Patterson and Bartley are adeptly shaping a new politics of visibility for the often overlooked or disregarded Caribbean subject.

•

See a portfolio of work by all fourteen Young Talent V artists here.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, July 2010

Annie Paul is head of the publications section at SALISES, University of the West Indies, Mona. A writer and critic, she is associate editor of Small Axe and author of the blog Active Voice. Her website is anniepaul.com.