Turn of the tide

Holly Bynoe talks to Melanie Archer about exile, loss, and reconciliation, and exploring personal and communal archives in her Compounds series

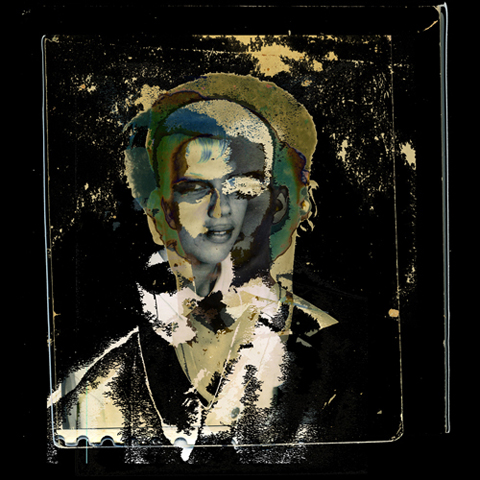

Pedigree (2009), by Holly Bynoe; digital collage, 40 x 40 inches. All images courtesy the artist

With deceptive simplicity, Holly Bynoe’s publication on the occasion of her 2010 MFA thesis is titled with a double set of geographic co-ordinates: 40ºN 74ºW | 13ºN 61ºW.

The first set of co-ordinates refers to New York — the most populous city in the United States. Home to some 8.4 million inhabitants, it is the centre of the greater NY metropolitan area — at roughly 6,720 square miles, one of the world’s largest concentrations of people and languages. This is where Bynoe lives and works. The second set of co-ordinates belongs to Bequia. Although the largest island of the Grenadines, it is a mere seven square miles, with a population estimated at 4,300. This is where Bynoe was born and raised.

Cartography is useful in pinpointing a migrant’s points of departure and arrival, but, in Bynoe’s case, these easy numbers belie the strong undercurrent of intricacy that has come to define her artistic output. Since 2009, she has been working through photography and image manipulation to create a series of Compounds — digital collages that often use her family’s own archival photographs to begin unfolding the concepts of exile, memory, and place, and what she refers to as “the spaces in between.”

These Compounds are characterised not only by the expected complexity of layering images one on top of the other, but by the subtraction of portions of a given image, which speak strongly of tensions created by absence and fragmentation and loss. Born roughly at the same time and conceptually inextricable from these visual works are Bynoe’s “writing pieces,” which also bear out a deep plunge into and exploration of the grey areas created by exile and otherness.

In writing about her work, Bynoe aptly refers to Walter Benjamin’s “fan of memory,” which provides significant clues to her practice and process:

He who has once begun to open the fan of memory never comes to the end of its segments; no image satisfies him, for he has seen that it can be unfolded, and only in its folds does the truth reside; that image, that taste, that touch for whose sake all has been unfurled and dissected; and now remembrance advances from small to smallest details, from the smallest to the infinitesimal, while that which it encounters in these microcosms grows ever mightier.

— Melanie Archer

On Deck (2009), by Holly Bynoe; digital collage, 30 x 40 inches

Brian (2010), by Holly Bynoe; digital collage, 25 x 35 inches

Fracture (2010), by Holly Bynoe; digital collage, 11 x 15 inches

The Fordes (2010), by Holly Bynoe; digital collage, 40 x 60 inches

•

In February 2011, via email, Bynoe answered a few questions about her Compounds series and ARC, the contemporary art magazine she recently launched with fellow artist Nadia Huggins.

Melanie Archer: You once commented that you’re in self-imposed exile. Could you talk a bit about this — how you came to be in exile and, more importantly, why you remain?

Holly Bynoe: I think a large contributor to the way I create is to be in between. In between thoughts, ideas, processes, and feeling. Ambivalence is always present when I occupy a space or place. I exiled myself in order to create, in order to explore the different states of absence that were present to me ever since my late teenage years. I moved away from home when I was seventeen, and my sense of stability was always in a state of flux. I exile myself because of fear — it is a terrible way to live — fear of rejection, judgment, and persecution. I am a warrior when confronted, but prefer to live my days in “wander” and “wonder” of traces and trails of human behaviour.

My time in exile is coming to an end, for several reasons, all of them closely related to loss and its metaphysical and emotional impact on the spirit and essence of one’s self. I feel as though an era in my life ended last year [Bynoe’s father died in 2010], and the time has come for me to move back to the land, become acquainted with its gestures, movement, and idiosyncrasies. In a greater sense I have begun to give myself permission to want to experience what it means to really occupy a space and have it become a part of my creative experience. I am also coming to terms with forgiveness and its numerous delicate properties.

New York is a beautiful place to live if one is in exile; it offers anonymity and a mash-up of everything. The absurd is prevalent in this metropolitan space, so it is quite hard to connect to what you experience and observe around you, yet you are always tapped into its kinetic energy, my personality rarely allows me to disconnect. It is quite the antithesis of growing up and becoming on a seven-square-mile island.

MA: Over the past few years, you have been making dense and multi-layered collages that seem to embrace both the nostalgic (in terms of archival photos and such) and the modern (in terms of process of assembly). Do you feel any tension in this polarity of old and new, and, if yes, do you welcome it?

HB: I have always been interested in the nature of two things interrupting each other. A compound is also a group of elements that work with each other, and by their natural deficiency or by providence they bond/cohere/unite to become something greater. In my imagery it doesn’t manifest as a parasitical relationship, but a symbiotic one, where elements of the past and present can coexist and function upon a shared plane or surface.

Even though I am working with the archive, it is not my only source of imagery. I use scans of objects — sand, hair, dirt, skin, maps, and objects that have an embedded familial connection — along with my photography and writing to start obfuscating the surface. Bringing these elements together has presented itself with permission — possibly naïvely — to understand trauma, truth, and legacy. It has given my images new structure and vocabulary without falling into sentimentality and nostalgia.

I find the prospects and future of digital technology really exciting, and I feel as though when used in a really self-aware and intuitive way it becomes chaotic and impractical to read a surface that has presented itself as distorted, chaotic, and vague. The veiling, masking, and revealing works tangentially to subvert and analyse a culture and an experience that cannot be essentialised and or simplified. It is a vulnerable position to put the viewer in; it requires work, and being perceptive towards the gestures of the artist.

Sinking Ship (2009), by Holly Bynoe; digital collage, 20 x 30 inches

The Queen in Red Anthems (2009), by Holly Bynoe; digital collage, 20 x 30 inches

MA: How do you go about creating your collages? Do you look for visuals that might fit an idea, or do the works evolve organically from either a physical or mental collection of images?

HB: I graze for long periods of time and ruminate over the possibilities of images — their use, function, criticality, and absurdity. I think about images and how their purposes in my life seem to change every day. A year ago it was about coming to terms with myself in a highly critical academic environment. Right now it is about an impression — both physical and emotional. My family’s archive was the logical place to start, and that branched out to include my extended family, but also images that bore some sort of connection to the experience that I was trying to translate.

So I started to curate the images for my collages based on the fact that I wanted to involve first a personal narrative, and second a narrative without boundaries and borders, which took me into the bowels of the New York Public Library archives. I looked for hours, and wrote down my encounter with late-nineteenth-century boatyards, steel workers, identification forms, various colonised views of the East and West, plantations, and ceremonies, but mostly the landscape.

After my initial selection, the images are then scanned. The scanner is my primary image-capturing device. I edit the selection down to five images. The criteria for this choice are a mixture of form, composition, the narration and voice within the physical aspect of the photograph, and its textural presence. I start composing, erasing, and layering. The layers that I work with can amount to between ten and fifty different pieces. I cut, splice, erase, select, blend, and colour until a form takes shape. I rarely have the end product in mind or completed until there is a foundation for me to observe.

I think, abstract, and add until the composite attempts in some way to deliver a narration that presents a perspective satisfying my intention. I started working with faces in 2010, and I feel as though I have to return to a less conflicting plane before I can fully move forward and analyse what the Compounds are and how I can bring them forward into a space that is more complex or complicated in physical form. I have been thinking about steel hulls and vessels and the materiality or impression of a digital image in conjunction with a form that is strict/rigid/controlled. In the end, the work has to serve a purpose, and interact with a culture that is already codified. It has to stand on its own without my whispers and breakdown — I think there is already a lot of it in motion throughout the work.

MA: In 2009 you introduced your “writing pieces.” What role do these writings play in what you consider your creative output? Do you consider them part of your artistic practice, do they occur in conjunction with your artistic practice, or are they supplemental? Can they even be separated and examined in this way?

HB: Writing for me is a way to construct a certain objectivity when coupled with imagery. I look at my writing as an extension of the way I construct narratives and inject a certain voice that works in contradiction to the emotion that my images are embedded with. There is the presence of an unreliable voice that is sometimes relating a contemporary experience or dissecting a section of a lived experience.

Rhyming, myth, and imagination are more prevalent through the way language works to reinforce the experiential tangles of belonging. Sometimes the writings vacillate between English and a colloquial dialect. Strange thing — I never really allowed myself to deconstruct the idea of the mother tongue until I found myself battling with the fact that my timbre, utterances, and presence were becoming compromised. It was one of those decisions where I just didn’t care how I sounded, and if you understood me or not. It was a way for me to reclaim my space.

Language is the way that we as a region have come to understand community and how we relate to authority, dominance, systematic control, and the colonisation and reclamation of the landscape. I think about the experience of coming into contact with writing that disarms me, and in particular Untitled (1993) by Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Christopher Wool. Untitled disrupts the particles of language and layout; letters can be read backwards, vertically, and such. The subversion of how the body encounters that piece is like a battle to me, where I am completely defeated, first by the form, its subversion, and then the content.

I think now the basis of my practice is steeped in the methodology of thought materialising on a page in handwriting and being broken down, thought about, and assimilated into a fragment, or what can often be parts of a whole story, scene, event, or realisation. I am not always certain as to what I am assembling or dictating, but I do know that the images I create from my writings can live and exist separate to my visual images, and vice versa. However, I think together they discourse and enliven the experience of negotiating and informing identities that have been lost in translation. I think I am working within a tradition that has given me permission to be spontaneous, haphazard, and ironic. I juxtapose these elements to create a more concrete definition of what Creolité means — although I am moving away from positioning my work and its construction within identity politics, and thinking about it in a structural manner.

MA: In your writings about your work (or your writings that are your work), you speak about losing oneself geographically and historically. You also talk about the romance and heartbreak of exile and you refer to authors — V.S. Naipaul, Dionne Brand, Derek Walcott, Edward Said — all of whom deal with the topic of being away from home. How have those particular writings or authors informed your artistic practice?

HB: Brand’s A Map to the Door of No Return gave me permission to give myself permission. She developed an intriguing tour de force, mapping the wanderings of the individual and collective dislocations central to a West Indian experience. Even though her words resonate specifically to race, I can’t help but find myself deep within the maze she is constructing, reconfiguring, and in many ways failing at really defining. Her profound treatment of memory, the sea, dispersal, and collective experience is an elaborate tangential collection of features that have shaped Caribbean identity for centuries. Her investigation into post-memory is grounded within the loss I feel as a creator battling with history, lineage, narrative, and fiction.

Naipaul and Walcott are, by now, models — their influence is almost as ubiquitous and as prevalent as water on the shoreline. Walcott’s Omeros and its occupation of a figure in the trenches of imagination and influence coupled with Naipaul’s rumination on occupying space that is critical and lacking of reverence are powerful guides. They have both influenced multitudes of contemporary writers and visual artists. Isaac Julien’s multi-channel video installation and adaptation of Walcott’s Omeros is one of the pinnacle achievements of how literary influence can be translated to visual art. I create work when I am reading; it is one of my identifiable triggers.

MA: Could you talk a bit about if or how you think the reception or reading of your work varies between “home” and, say, New York? Is there a divide?

HB: I haven’t had the opportunity to introduce my work or current practice to the Caribbean, and definitely not to St Vincent. I can’t really say what the dialogue would be, or if the public would have any clear understanding of my processes, surfaces, or critique. I have only had the opportunity to show my work in the United States. However, I have a pretty solid Caribbean following in the US who give me the support I need. Most of them are also practising artists who also don’t have the infrastructure that would be necessary for showing or promoting work in their varied islands. I think larger countries like Jamaica, Trinidad, and Barbados to some extent have a vibrant art scene that is supported by various institutions, national governments, and the private sector.

MA: How do you balance your artistic practice with your work at ARC? Does one feed into the other? And out of what concerns did the magazine develop?

HB: ARC was born out of the idea that Nadia Huggins and I had to find a project to work on so we could isolate our varied strengths and weaknesses to create something that would extend itself and have a collective and necessary impact on our social spaces and geography. To be honest, I feel as though I can’t critique the brain drain and contribute to it at the same time. It began to bother me, the conflict between thought and action, so I also had to start thinking about a positive and meaningful way to make my entry back home.

I have been devoted to forming a community around me to support my work, and I feel its strength wax and wane. ARC is also presenting itself as a way to keep up with what is going on, and the motions that I really can’t invest in unless the possibility of a project like this exists. It is in one way a selfless endeavour where I see the publication advancing conversation, dialogues, and opportunities for us all.

I haven’t made work in a while, and it is mostly due to the fact that making and taking photographs makes me sad right now. I am not sure if I am still in the process of grieving, but it certainly feels as though the iceberg or blockage is still very present to my attitude of going back to text, images, and narratives. In many ways I want to start to dissect and digest the loss, and I can’t — there is no rushing these things — as my father was a major focus and inspiration for my work through the last three years. That being said, I think I am always working on expanding my views of photography and its changing environs, looking at work, and in dialogue with artists, etc. In that way, ARC is the perfect conduit for me to place, channel, and develop all of the extensions of my practice.

I think they are harmonious right now, although I feel as the urge comes back to approach a new body of work or a new idea that one will have to wait while I concentrate on the other. I can compartmentalise only to a certain extent, and depending on my level of participation and interest, I move with the tide and pull of the work always.

Imperial (2010), by Holly Bynoe; digital collage, 40 x 60 inches

•

Read an interview with Bynoe and Huggins on the launch of ARC, posted at Antilles in January 2011.

•••

The Caribbean Review of Books, March 2011

Holly Bynoe is a visual artist and writer who was born and raised in Bequia, St Vincent and the Grenadines. She moved to New York City in 2001, back to Bequia in 2006, and in 2008 returned to New York, where she currently lives and works. In 2010, Bynoe received an MFA in advanced photographic studies from the International Centre of Photography/Bard College. She has exhibited internationally in solo and group shows. She is also co-founder and editor-in-chief of ARC magazine.

Melanie Archer is a former managing editor of DAP/Distributed Art Publishers in New York. She is now based in Trinidad.